I’d be wary of any movie star who invites me to his hotel room to “read poetry” unless said star was documented poetry nut, Bill Murray.

Earlier this year, Leigh Haber, book editor of O, The Oprah Magazine, reached out to Murray to see if he’d share some of his favorite poems in celebration of National Poetry Month. In true Murray-esque fashion, he waited until deadline to return her call, suggesting that they meet in his room at the Carlyle, where he would recite his choices in person.

Such celebrity shenanigans are unheard of at the Chateau Marmont!

Murray’s favorite poems:

“What the Mirror Said” by Lucille Clifton

At the top of the page, Murray reads the poem at a benefit for New York’s Poets House, adopting a light accent suggested by the dialect of the narrator, a mirror full of appreciation for the poet’s womanly body. Clifton said that the “germ” of the poem was visiting her husband at Harvard, and feeling out of place among all the slim young coeds. Thusly does Murray position himself as a hero to every female above the age of … you decide.

“Oatmeal” by Galway Kinnell

Kinnell, who sought to enliven a dreary bowl of oatmeal with such dining companions as Keats, Spenser and Milton, shared Murray’s playful sensibility. In an interview conducted as part of Michele Root-Bernstein’s Worldplay Project he remarked:

… it doesn’t seem like play at the time of doing it, but part of the whole construct of the work, and even though the work might be extremely serious and even morose, still there’s that element of play that is just an inseparable part of it.

“I Love You Sweatheart” by Thomas Lux

Murray told O, which incorrectly reported the poem’s title as “I Love You Sweetheart” that he experienced this one as a vibration on the inside of his ribs “where the meat is most tender.” It would make a terrific scene in a movie, and who better to play the lover risking his life to misspell a term of endearment on a bridge than Bill Murray?

“Famous” by Naomi Shihab Nye

Alas, we could find no footage of Nye reading her lovely poem aloud, but you can read it in full over at The Poetry Foundation. It’s easy to see why it speaks to Murray.

Related Content:

Bill Murray Reads Poetry at a Construction Site: Emily Dickinson, Billy Collins & More

Bill Murray Reads Great Poetry by Billy Collins, Cole Porter, and Sarah Manguso

Bill Murray Gives a Delightful Reading of Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (1996)

Bill Murray Reads Poetry at a Construction Site: Emily Dickinson, Billy Collins & More

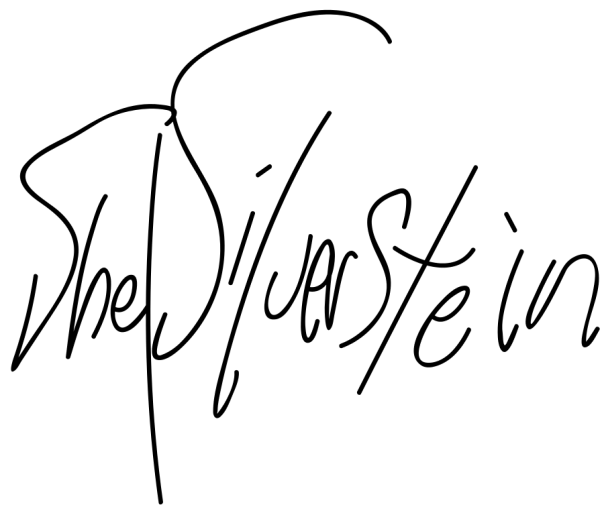

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.