Among the many other 50ths commemorated this year, one will largely go unnoticed by the U.S. press, given that it happened in France, a country we like to ignore as much as possible, and concerned the politics of anarchists and communists, people we like to pretend don’t exist except as caricatures in scare-mongering cartoons. But the French remember May 1968, and not only on its fiftieth. The wildcat strikes, student marches, and barricades in the Latin Quarter haunt French politics. “We’re slightly prisoners of a myth,” laments historian Danielle Tartakowsky.

The international historical events surrounding the strikes and marches are well-known or should be. The founding ethos of the movement, Situationism, perhaps less so. Reading Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and the 1968 movement’s other essential texts can feel like looking into a funhouse mirror.

The 1966 pamphlet manifesto that began the student agitation—“On the Poverty of Student Life”—might sound mighty familiar: it has no kind words for consumerist student radicals who “convert their unconscious contempt into a blind enthusiasm.” Yet they have been attacked, it clarifies, “from the wrong point of view.”

Since we seem to be, in some denatured way, reliving events of fifty years ago, the thinking of that not-so-distant moment illuminates our circumstances. “If there’s one thing in common between 1968 and today,” remarks Antoine Guégan, whose father Gérard staged Paris campus sit-ins, “it’s young people’s despair. But it’s a different kind of despair…. Today’s youth is facing a moment of stagnation, with little to lean on.” Despite the riotous, bloody nature of the times, a global movement then found reason for hope.

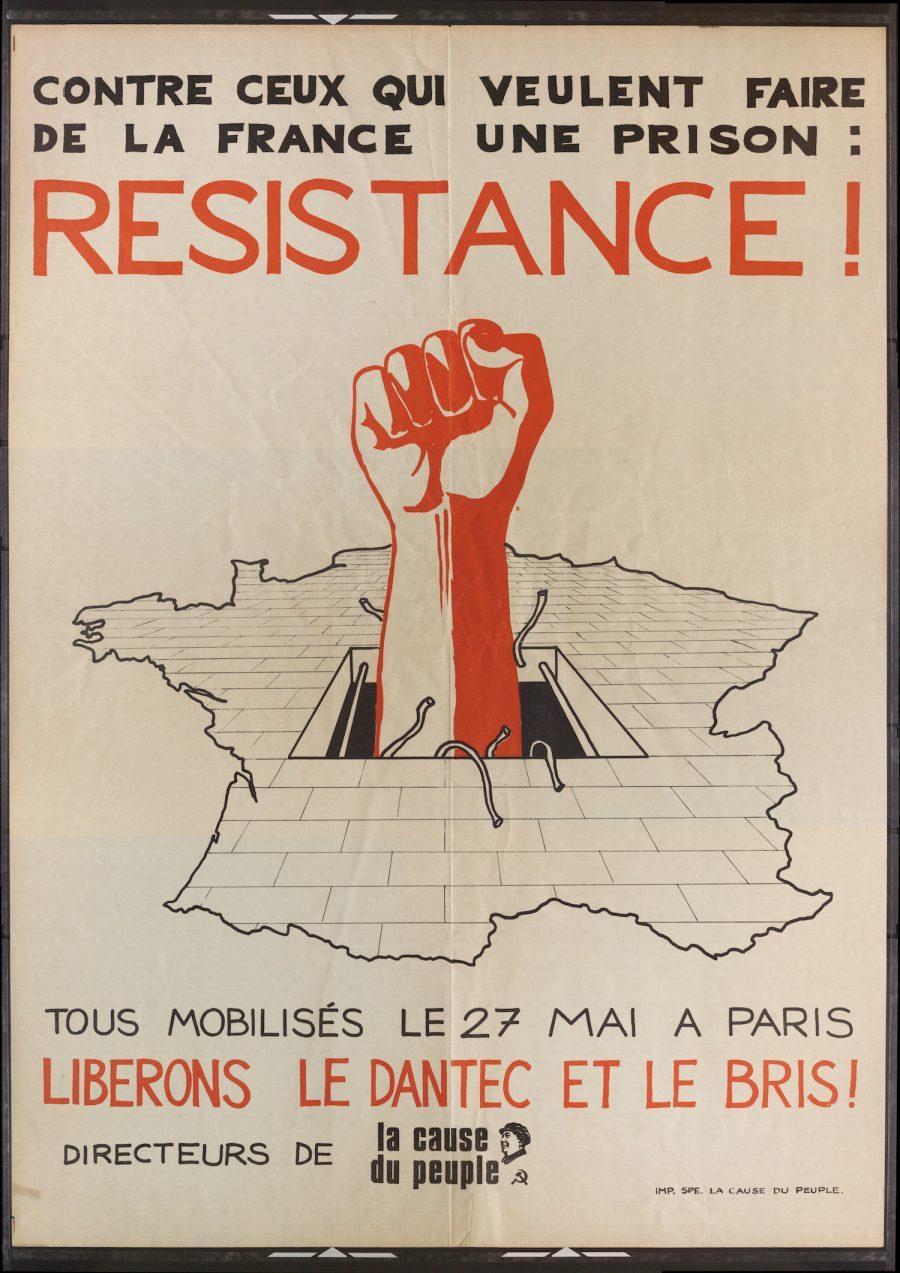

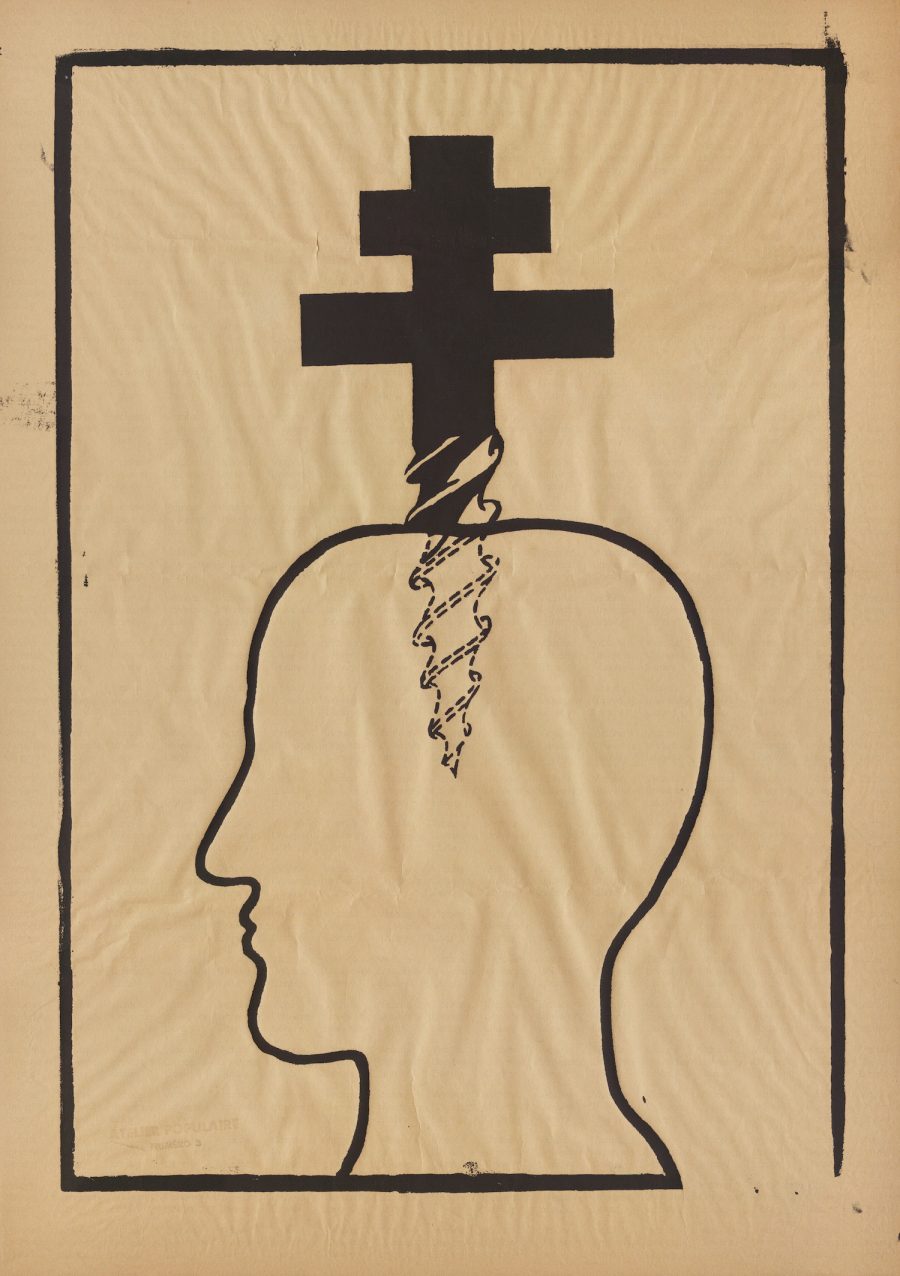

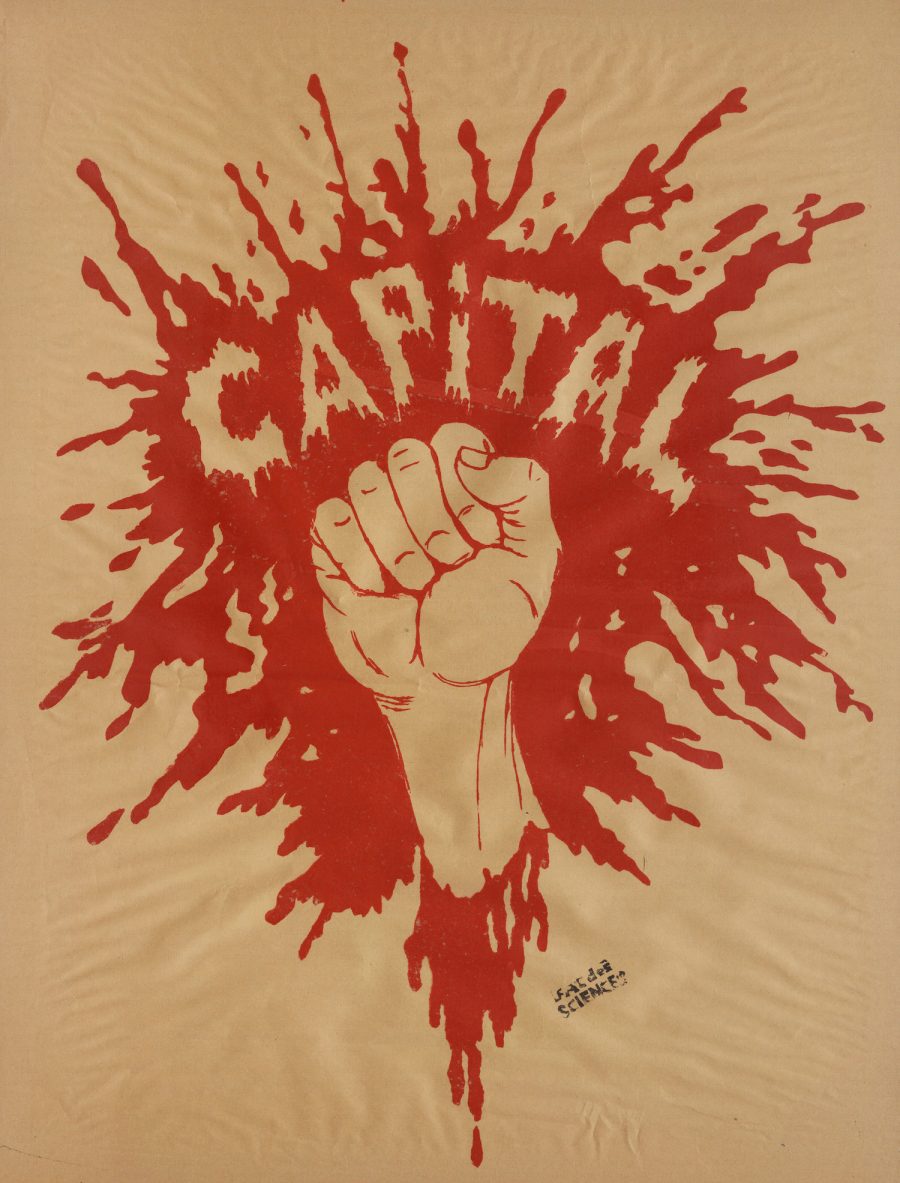

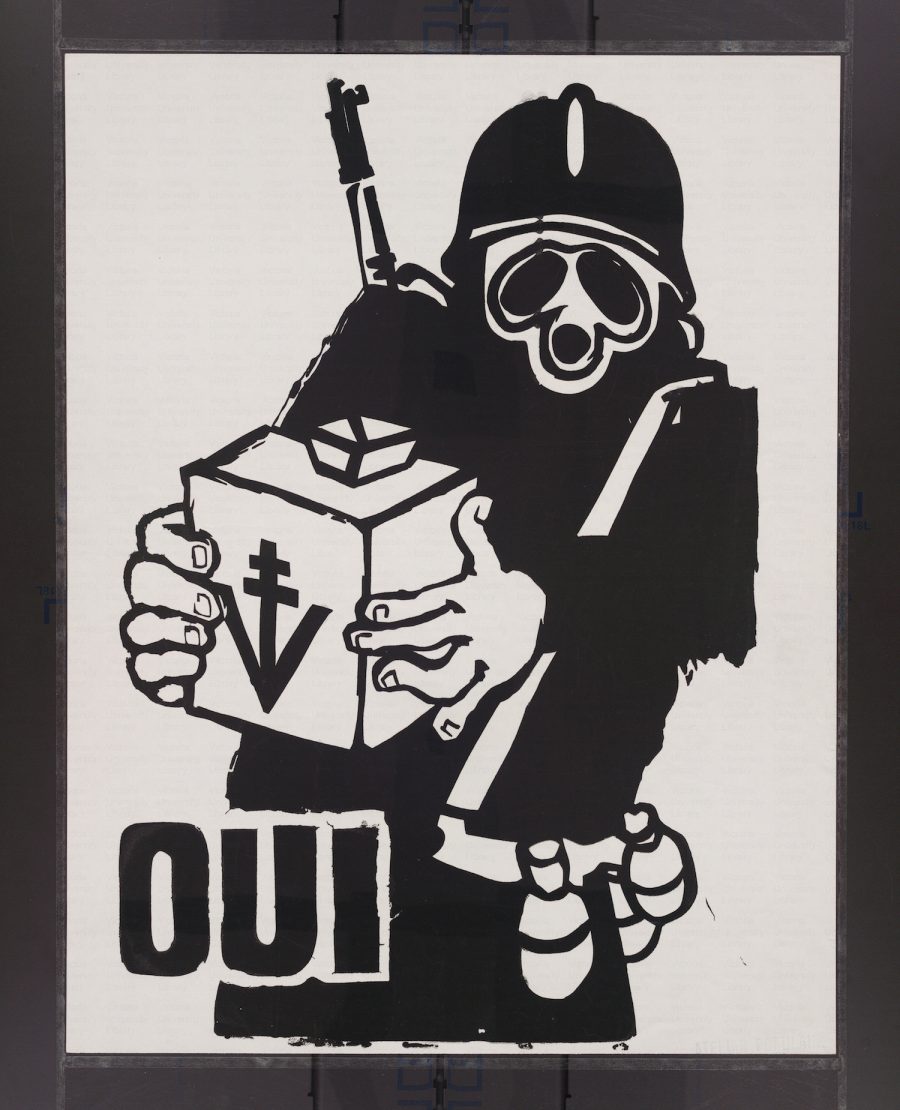

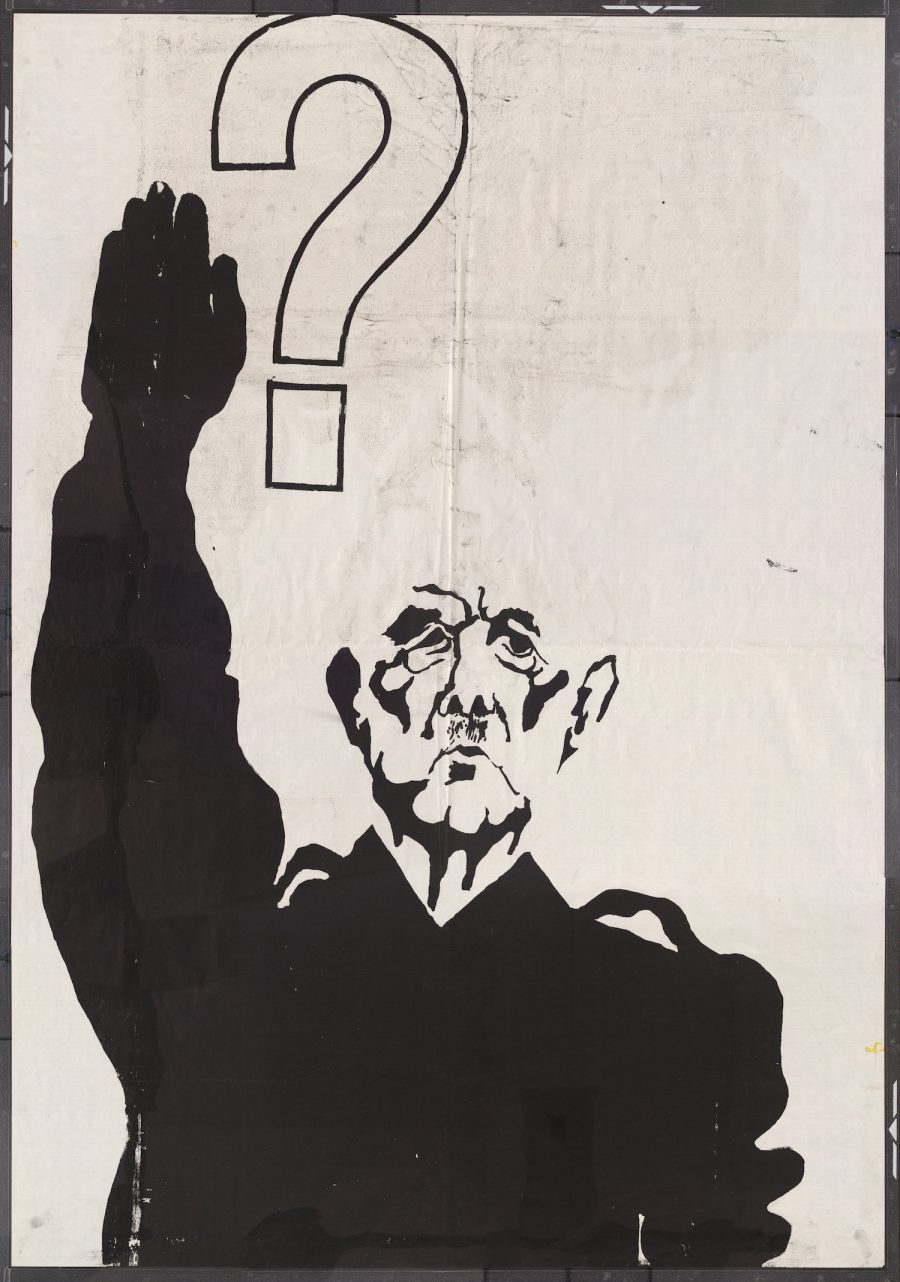

We see it reflected in the defiant art and cinema of the time, from revolutionary work by a 75-year-old Joan Miró to vérité film by 20-year-old wunderkind Philippe Garrel. And we see it, especially, in the huge number of posters printed to advertise the movement, radical graphic designs that illustrate the exhilaration and defiance of the loose collective of Marxists-Leninists, Trotskyites, Maoists, Anarchists, Situationists, and so on who propelled the movement forward.

Last year, we featured a gallery of these arresting images from the Atelier Populaire, a group of artists and students, notes Dangerous Minds, which “occupied the École des Beaux-Arts and dedicated its efforts to producing thousands of silk-screened posters using bold, iconic imagery and slogans as well as explicitly collective/anonymous authorship.” Today, we bring you a huge gallery of more than 300 such images, housed online at Victoria University in the University of Toronto.

Some of the images are downloadable. You can request downloads of others from the university library for private use or publication. These posters represent a movement confronting an oppressive society with its own logic, a society of which Debord wrote just the previous year, “the spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.” There is no understanding of the events of May 1968 without an understanding of its visual culture as, Debord wrote, “a means of unification.” Enter the gallery of posters and prints here.

Related Content:

A Gallery of Visually Arresting Posters from the May 1968 Paris Uprising

Bed Peace Revisits John Lennon & Yoko Ono’s Famous Anti-Vietnam Protests

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness