Today we have a guest post by William Rankin, director of educational innovation, associate professor of medieval literature, and Apple Distinguished Educator, Abilene Christian University. ACU was the first university in the world to announce a comprehensive one-to-one initiative based on iPhones and iPod touches designed to explore the impact of mobility in education. For the past year, they have been considering the future of the textbook. Rankin, who made a brief appearance on NBC Nightly News last night, does a great job here of putting the new Apple iPad in historical context and suggesting why it may solve the great informational problems of our age.

Today we have a guest post by William Rankin, director of educational innovation, associate professor of medieval literature, and Apple Distinguished Educator, Abilene Christian University. ACU was the first university in the world to announce a comprehensive one-to-one initiative based on iPhones and iPod touches designed to explore the impact of mobility in education. For the past year, they have been considering the future of the textbook. Rankin, who made a brief appearance on NBC Nightly News last night, does a great job here of putting the new Apple iPad in historical context and suggesting why it may solve the great informational problems of our age.

It may seem strange in the wake of a major tech announcement to turn to the past—570 years in the past and beyond — but to consider the role of eBooks and specifically of Apple’s new iPad, I think such a diversion is necessary. Plus, as regular readers of Open Culture know, technology is at its best not when it sets us off on some isolated yet sparkling digital future, but when it connects us more fully to our humanity — to our history, our interrelatedness, and our culture. I want to take a moment, therefore, to look back before I look forward, considering the similarities between Gutenberg’s revolution and recent developments in eBook technologies and offering some basic criteria we can borrow from history to assess whether these new technologies — including Apple’s iPad — are ready to propel us into information’s third age.

In the world before Gutenberg’s press — the first age — information was transmitted primarily in a one-to-one fashion. If I wanted to learn something from a person, I typically had to go to that person to learn it. This created an information culture that was highly personal and relational, a characteristic evidenced in apprenticeships and in the teacher/student relationships of the early universities. This relational characteristic was true even for textual information. The manual technology behind the production and copying of books and the immense associated costs meant that it was difficult for books to proliferate. To see a book — if I couldn’t afford to have my own copy hand-made, a proposition requiring the expenditure of a lifetime’s worth of wages for the average person — meant that I had to go visit the library that owned it. Even then, I might not be allowed to see it if I didn’t have a privileged relationship with its owners. So while the first age was rich in information (a truth that has nothing to do with my personal bias as a medievalist), its primary challenge involved access.

Gutenberg’s revolution, ushering in the second age, solved that problem. Driven by one of the first machines to enable mass-production, information could proliferate for the first time. Multiple copies of books could be produced quickly and relatively cheaply — Gutenberg’s Bible was available at a cost of only three years’ wages for the average clerk — and this meant that books took on a new role in culture. This was the birth of mass media. Libraries exploded from having tens or perhaps a few hundred books to having thousands. Or tens of thousands. Or millions. And this abundance led to three distinct revolutions in culture. Though the university initially fought its introduction, the printed textbook provided broad access to information that, for the first time, promised the possibility of universal education. Widespread access to bibles and theological texts fueled significant transformations in religion across the Western Hemisphere. And access to information, philosophy, and news led to the dismantling of old political hierarchies and some of the first experiments with democracy (have you ever stopped to notice how many of the American revolutionaries were involved in printing and publishing?).

But the proliferation of information had a dark side as well, creating a new challenge for the second age: finding. Where information had been previously organized primarily along relational lines, its abstraction into mass-produced books in enormous collections led to a need for all sorts of new technologies aimed at solving the problem of finding: card catalogues, bibliographies, indices. A barrier of symbolic complexity emerged between people and information for one of the first times in history. And the superabundance of information created a world that by necessity had to be divided into smaller and smaller subsections for organizational reasons. As people began to feel increasingly disconnected from information and as its relational and contextual aspects began to fade, we saw a transformation in teaching and learning. Hands-on apprenticeships and small teacher/student cohorts began to disappear, replaced by teachers delivering carefully parsed and categorized information to “standardized” students, all while trapped in classrooms isolated from the world in order to limit “distraction.” Mirroring the age’s informational technology, the assembly-line model of education had appeared, one that was becoming increasingly untenable by the close of the 20th century.

Luckily, and enabled by new technologies, that model of education is beginning to change. Access and finding aren’t particularly problems in the world of the Net and universal search, and many of the teaching strategies of the last age — memorization, repetition, a focus on information over application — all targeted at solving the problem of finding seem increasingly irrelevant. In under a second and without having to understand any bibliographical technicalities, I can type a search term into Google’s deceptively sparse search window and voilà! 50 million hits. It’s a level of access and ease of discovery unprecedented in human history — a new informational age. And this new informational age is cursed with a new problem: 50 million hits.

It has become virtually impossible for a person to assess the quality, relevance, and usefulness of more information than she can process in a lifetime. And this is a problem that will only get worse as information continues to proliferate. But a quick look at popular technologies shows some of the ways people are working to address it. Social networking leverages selected communities to recommend books, restaurants, and movies. Context- and location-aware applications help focus search results and eliminate extraneous complexity. And customization and personalization allow people to create informational spaces that limit the intrusion of informational chaos.

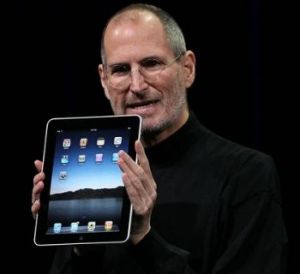

More than many other companies, Apple has understood this challenge for some time — and has leveraged these same popular technologies to help solve it. One has only to look at the ecosystem connecting the iPod and the iTunes store to see a prime example. Of course, Apple is not the only company to do so; Amazon, Google, and others have built similar solutions for people using their services. But with the iPhone and iPod touch, and now with the new iPad, I think we’re beginning to see something really interesting develop. Especially in the context of eBooks, I’m increasingly convinced that we’re at the dawn of a change as radical as that driven by Gutenberg’s invention.

How can I make such an audacious claim? How can one even assess whether a particular eBook technology will be successful? Any genuine solution will have to address the problems of the current informational age — and it will need to continue answering the problems of the previous informational ages. From what I’ve seen, Apple’s new iPad is the first device to promise this (even if that promise isn’t yet fully realized). That is what makes it such a compelling candidate to be the first platform that serves true digital books.

Of course, as you may note from that last phrase, I don’t believe we’ve yet seen a true digital book. Yes, we have eBooks on a variety of digital devices, but they haven’t yet taken real advantage of their electronic status. Books that are static, don’t allow customization, don’t connect with other information on the device, and don’t leverage social connectivity aren’t the future, no matter how sophisticated the device that serves them. They’re simply the past repackaged. Their repackaging may be interesting in some circumstances (airplanes and commutes anyone?) but the current crop of eBooks and eReaders simply doesn’t address the informational problems of the third age robustly enough to be compelling for the long term. This is certainly one of the reasons that the Kindle pilot at Princeton didn’t go very well. Don’t misunderstand — the Kindle, like the nook and the Sony Reader, addresses some important informational problems. But I don’t believe it has put the whole package together in a way that can drive real cultural change, and that means its adoption will be limited.

Given what I’ve seen of its features and approaches, the iPad shows the promise to engender such a change, though much development will have to take place for it to realize its potential. Nonetheless, the innovation it offers in three critical areas is especially compelling: accessibility, participation, and customization. Central to all three of these is the fact that the iPad is not a single-use, standalone device; it’s a powerful, converged platform with robust development tools and capabilities. Although it has come to market well behind other eReader devices, this aspect alone makes the iPad a credible platform for the future of the book.

One difference between the iPad and other tablet or eReader devices is its new level of accessibility. I don’t merely mean accessibility in the traditional sense of that word — that this device is portable, generally affordable (especially when one thinks of textbook costs), and solidly connected. Many devices, including the current generation of eReaders (and full-blown laptops), offer this kind of accessibility. Instead, I would argue that the key accessibility feature of the iPad is its apparent “lack” of an interface (a feature Apple’s marketing is working hard to underscore). Unlike all of the other similar devices (including those running Apple’s standard OS), which require users to learn to negotiate complex symbolic interfaces — files, folders, hierarchies, toolbars, navigational buttons — the iPad limits or even eliminates these in favor of touch, an approach intuitive even to those too young to read. Pioneered on the iPhone and iPod touch, this technology offers a simple way for users to interact with and control content. So instead of seeing an image on the screen and having to use a button on the side of the device to “turn the page,” I simply drag my finger across it, and the digital page behaves as though it were a real object in the real world. The collapsing of symbolic complexity into the simplicity of touch enables participation by new groups of people — even relative technophobes — and this mirrors the increased accessibility offered by Gutenberg’s revolution while lowering the barrier characteristic of most recent technologies.

In Gutenberg’s case, the increase in accessibility led to a dramatic increase in cultural participation, and this is another way the iPad differentiates itself from many of its peer devices. Whereas the current generation of eReaders limits most users to the consumption of information, mirroring the control of publishing that emerged during the last informational age, the iPad offers (and certainly promises to offer more fully) a new set of tools for content creation. Put in the hands of readers and students, the robust capabilities of its new version of iWork, combined with access to the complete range of apps on the App Store and an entirely new generation of native apps, the iPad could provide access to professional-quality creative tools that empower a new set of participants. For those interested in culture and creativity, this is an exciting prospect.

Finally, the iPad’s blend of social and contextual technologies and its ease of customization offer useful ways for the device to help users sort, focus, and control the information around them. The iPad’s networking capabilities, linked to a new generation of digital books, could help people discover both new texts and the members of a discussion group who could help them process what they’re reading. Combined with a portable format that allows readers to carry their books into various contexts, this could be incredibly powerful. One imagines, for example, a field-guide to forests linked to live discussion partners, allowing a reader to discover the forest in a new and engaging way that offers the advantages of both the first and second informational ages. Yet this sort of capability also reveals an area where the iPad falls surprisingly short: its lack of a camera (let alone two, one forward and one backward facing) means the device has limited capabilities for interesting emerging technologies like augmented reality — a staple of recently-developed apps. In terms of future eBooks, a volume of Hemingway that could alert readers that they were only two blocks from the café Les Deux Magots, for example, and offer an augmented tour of the place or that could direct the reader of Brontë to a moor would be transformational indeed. Perhaps we’ll see such capabilities on iPad 2.0.

Will the iPad’s mix of eBooks, media, and creation tools change the world? It’s difficult to say. At ACU, we’re certainly looking forward to getting these devices in the hands of teachers and students so that we have a clearer sense. But it’s already clear that in providing a device that addresses the core issues of all three information ages, Apple’s iPad is the first contender to show genuine promise.

I like Apple (I own a Mac and an iPhone) and don’t plan on returning to PC land any time soon. But, so early in the game, does ACU need to be so slavish in its praise of the corporate monster that is Apple? Me thinks a little brake tap might be in order.

It’s sad that many of the problems Apple has generated in it’s short past with the Appstore are almost willfully ignored. I expected a more neutral and honest or at least critical view from openculture.com. I myself too have several apple computers and products. But like almost any iphone users I know, I jailbreaked it to escape the power Apple has over it’s devices. This won’t be a device where content will thrive to openness but one where every publisher has to answer to Apple or gets removed from the Appstore, as they have done it in the recent past more times then I wish to remember.

Iceline, funny you failed to mention the power of traditional publishers and media over content and artists. I’m not so sure Apple is the evil here.

I agree with the spirit of the critiques here, but understand that I was not intending to do a thoroughgoing critique of the the iPad. Instead, I was working to consider the future of the book and to discuss how one might evaluate one device versus another. Note that while I’m interested in the iPad’s capabilities and see it as having distinct advantages over the Kindle, for example (a device costing virtually the same), I don’t believe the iPad’s potential has been reached. Still, it’s clear that books are moving to a digital format — indeed, that they need to in order to address some of the problems of the current information age — and we need to understand some of the factors that will influence that move. Obviously, questions of rights, openness, interactivity, and cost will have to figure in, but such issues presume a platform a platform that is worth considering seriously from a technical standpoint first, and that’s what I was working to establish here. Thanks again for your comments, and I think it will be interesting to see how people and content converge around these devices.

Thank you for this excellent and thoughtful post! History gives us so much perspective and important context. Hopefully as you say the forces that strive to lock up content won’t win out and only deliver us “static” content, prepackaged for us by corporations for easy consumption… every book should be searchable, quotable, attributable. I should be able to download an electronic copy when I buy a paper one! And the device shouldn’t be crippled unduly in its capabilities solely for profit seeking, and limit its promise. I’m sure a future version will have a camera and allow for augmented reality; Apple is surely waiting to see what applications will be popular for the device before trying to add too much to it right off the bat.

Back in the 80s, I owned a bookstore and watched as people spent more and more time watching videos rather than reading. Even then, we discussed the future of print and could envision a time when every book/magazine/newspaper would be digitized to read on our computers and lines would blur between text, graphics and movies. (I once tried to convince some investors to go out and purchase the digital rights from publishers, realizing that they could do so for a song — few considered the end of ink and paper 20+ years ago.) We also knew people who had worked at Xerox labs in Rochester in the 70s and had laid out the future of computers becoming portable notebooks that could be used and tossed around like schoolbooks.

That’s why the iPad as a perfect disseminator of “books” just doesn’t seem so revolutionary.

Conversely, access to the internet and its unlimited storehouse of info from virtually anywhere on the planet is the element that few envisioned. Moreover, the internet as a exchange for lousy information, unreasoned opinion, infinite blather, ultra-mundane and ridiculous images/videos, etc. isn’t something that any of us who were thinking about a future of easy access to books, news, art and movies ever considered. It is the true revolution.

It is interesting to wonder if Apple is doing a great service in this revolution by trying to figure out a way for publishers/producers/directors to make enough money so they can continue to act as an alternative set of filters to the viral popularity that now determines what many people spend their time viewing online. Whether anyone or any group should be able to trump the democratization of truth, power, culture, or taste is the story here.

Just wondering why this article is up but there isn’t an iPad app for Open Culture. Make a brutha happy.

I do appreciate what you said: technology is at its best not when it sets us off on some isolated yet sparkling digital future, but when it connects us more fully to our humanity — to our history, our interrelatedness, and our culture.

Oral. Written. Print. Electronic. Digital. The iPad is part of at least the 5th age of information.