In the summer of 1942, Jack Kerouac followed in the footsteps of Joseph Conrad and Eugene O’Neill and went to sea. After dropping out of Columbia University the previous Fall, the 20-year-old Kerouac signed up for the merchant marine and shipped out aboard the U.S. Army Transport ship Dorchester.

Although World War II had broken out at about the time of his departure from Columbia, Kerouac’s motives for going to sea were more personal than patriotic. “My mother is very worried over my having joined the Merchant Marine,” Kerouac wrote in his journal at the time, “but I need money for college, I need adventure, of a sort (the real adventure of rotting wharves and seagulls, winey waters and ships, ports, cities, and faces & voices); and I want to study more of the earth, not out of books, but from direct experience.”

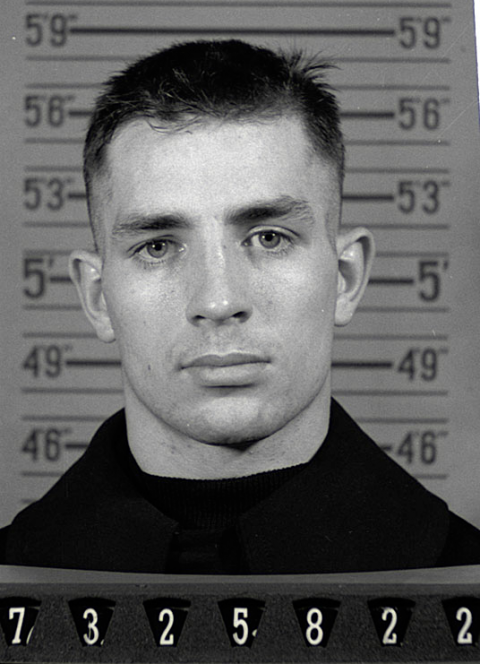

In October of 1942, after completing a voyage to and from an Army command base in Greenland (which he would later write about in Vanity of Duluoz), Kerouac left the merchant marine and returned to Columbia. That was lucky, because most of the Dorchester’s crew–more than 600 men–died three months later when the ship was torpedoed by a German U‑boat. But the restless Kerouac lasted only a month at Columbia before dropping out again and making plans to return to sea. In December of 1942 he enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve. He wanted to join the Naval Air Force, but failed an aptitude test. So on February 26, 1943 he was sent to the Naval Training Station in Newport, Rhode Island. That’s apparently when the photograph above was taken of the young Kerouac with his military haircut. It would have been right around the time of his 21st birthday.

Kerouac lasted only 10 days in boot camp. As Miriam Klieman writes at the National Archives, “The qualities that made On the Road a huge success and Kerouac a powerful storyteller, guide, and literary icon are the same ones that rendered him remarkably unsuitable for the military: independence, creativity, impulsivity, sensuality, and recklessness.” According to files released by the government in 2005, Naval doctors at Newport found Kerouac to be “restless, apathetic, seclusive” and determined that he was mentally unfit for service, writing that “neuropsychiatric examination disclosed auditory hallucinations, ideas of reference and suicide, and a rambling, grandiose, philosophical manner.” He was sent to the Naval Hospital in Bethesda Maryland and eventually discharged.

For more on Kerouac’s brief adventure in the Navy, read Kleiman’s Article, “Hit the Road, Jack! Kerouac Enlisted in the U.S. Navy But was Found ‘Unfit for Service’ ”

Related content:

Jack Kerouac Reads from On the Road, 1959

Jack Kerouac’s 30 Revelations for Writing Modern Prose