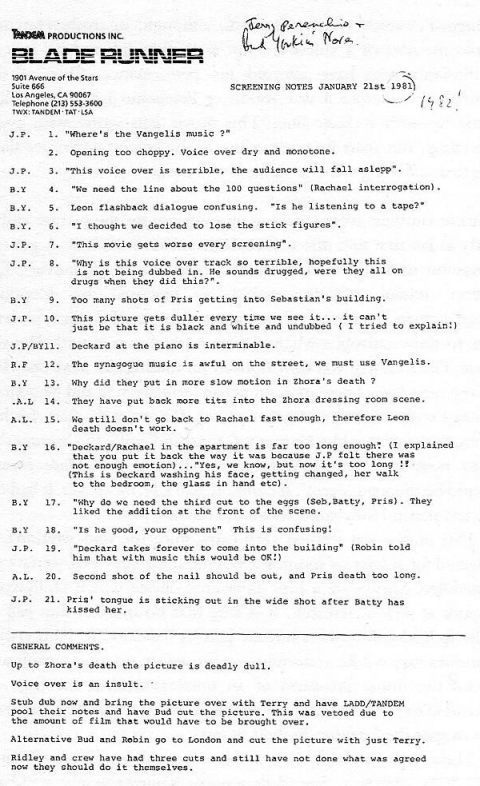

The story above—from our old friend James Grime of Numberphile and Cambridge University—has all the makings of weirdo Americana: bad amateur science, commercial ventures based upon the same, and a state legislature eager to embrace it all. In 1897, an amateur mathematician named Edwin Goodwin believed he’d solved an ancient problem ruled insoluble fifteen years earlier. He thought that he had squared the circle and could reasonably copyright Pi as 3.2. Yes, that’s right, after his “discovery,” Goodwin, a native of Indiana, decided to copyright his proof so that anyone using it outside of the state would have to pay him royalties.

But kindly, in a gesture of nativist goodwill (or political opportunism), Goodwin decided he would let his home state of Indiana use his proof for free for educational purposes. In fact, he said as much when he introduced a bill to the Indiana House of Representatives to rule his proof correct and grant him sole proprietorship. And, as sometimes happens in stories like this, the bill passed, unanimously, and the legislators were impressed. But one man wasn’t. By sheer chance, a professor of mathematics happened to be in attendance. While he declined to meet mathematics hero Edwin Goodwin, he did take it upon himself to warn the Indiana Senate of what was coming its way. Luckily for the state’s schoolchildren, the Senate threw the bill out, but not before a half-hour spent mocking its silliness.

But is the idea of squaring a circle ridiculous? Dr. Grime cites one Indian mathematician who proposed a somewhat feasible solution. And what exactly does it mean to “square a circle”? If you don’t know (and I don’t), you’ll have to wait till next time on Numberphile, when Grime and his team promise to explain it to us rubes.

Related Content:

The Math in Good Will Hunting is Easy: How Do You Like Them Apples?

The Enigma Machine: How Alan Turing Helped Break the Unbreakable Nazi Code

Incredible Mental Math Gymnastics on “Countdown”

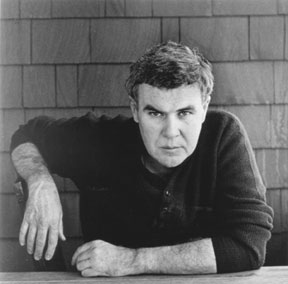

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness