“This is what we did. How did it happen? How could we?” –Dorothea Lange

The idea sounds counterintuitive given the violence we read about daily, but it is perhaps possible that human societies are slowly outgrowing xenophobia and war, as Harvard psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker has argued extensively. It’s also possible that Pinker’s view is an “article of faith” rather than fact. In any case, we can at least be heartened by one thing: If we do become better at learning from the past than repeating it, the primary documents will not have disappeared into a memory hole. The very same technologies that spread fear, bigotry, and disinformation across the globe also enable us to unearth humanity’s long history of bad decision-making and preserve the evidence in widely-accessible online archives.

One such archive, the Densho Digital Repository, contains “historic photographs, documents, newspapers, letters and other primary source materials” from the history of the Japanese in America—including, of course, a particularly regrettable historical episode, the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, a grim political expedient that offers lessons today to those who choose to learn them. Prominent among the archives’ many documents from the period is the Dorothea Lange Collection, almost 500 images taken by the famous photographer of “the many different stages of mass removal and incarceration” of Japanese Americans in California. The photographs (recently highlighted on Kottke.org) feature original captions written by Lange that contextualize the subjects and sometimes provide their names and a few biographical details.

The lives of Japanese internees were in fact documented by not one, but two famous American photographers, Lange and Ansel Adams. However, Adams—whose photographic series we featured in a previous post—gained access to an internment camp in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas on his own, through a friendship with the camp’s warden. Lange, on the other hand, snapped several hundred photographs while on official assignment with the War Relocation Authority. In 1942, the government hired her to document the removal and imprisonment of over 100,000 Japanese Americans in camps across the state.

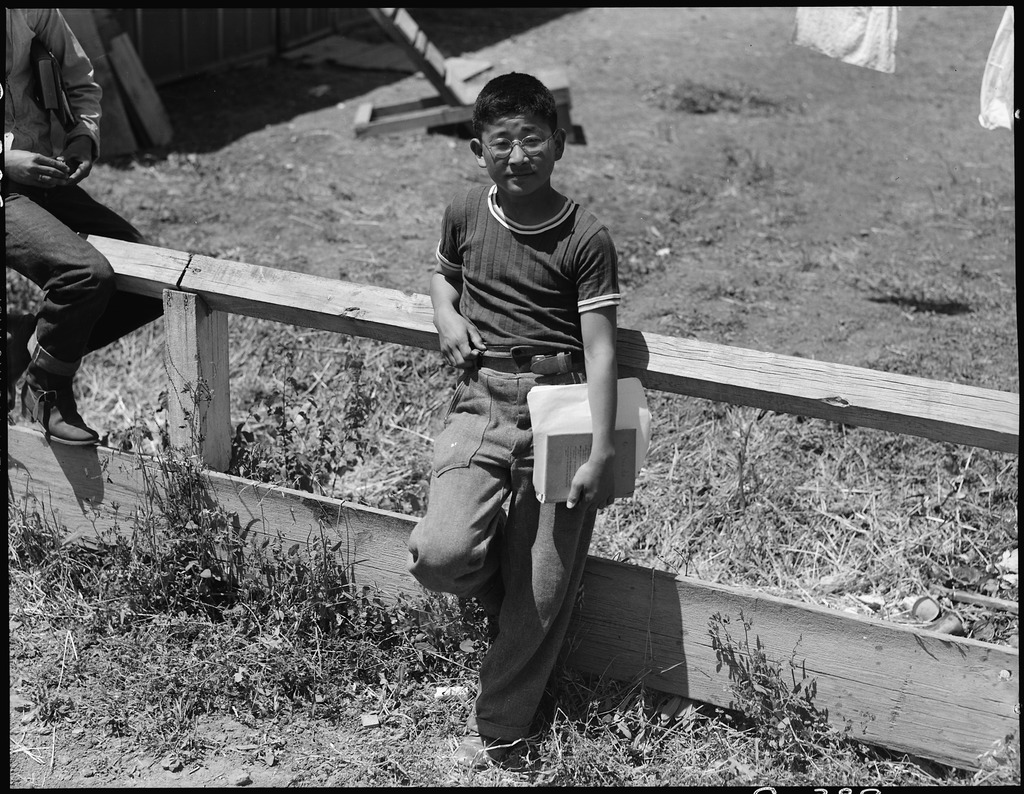

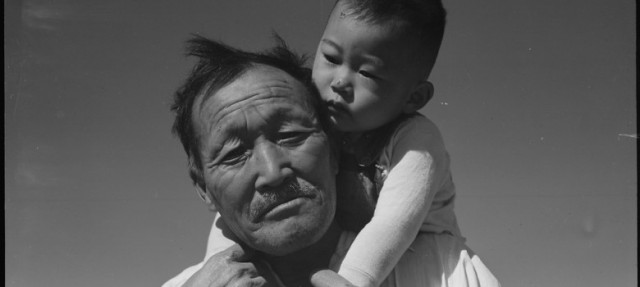

Lange’s photographs, writes Densho’s blog, have helped shape “the collective memory of Japanese American removal.” Despite the restrictions placed on her by the authorities—Lange could not shoot images of barbed wire, bayonets, or guard towers—“she managed to produce a body of work that at once captured the inhumane actions of the U.S. government and the humanity of the individuals being forced to leave their lives behind for the ‘crime’ of Japanese ancestry.”

Her photographs are “seemingly unstaged and unlighted,” writes Dinitia Smith in a New York Times review of Impounded, a book featuring many of the close to 800 photographs Lange took, most of which were only recently discovered at the National Archives, “where they had lain neglected for a half-century after having been impounded by the government.” Best known for her photos of Dust Bowl farm workers, Lange, writes scholar Megan Asaka at Densho, “was an odd choice, given her leftist politics and strong sympathy for victims of racial discrimination.” She was “appalled by the forced exile” and “confided to a Quaker protester that she was guilt stricken to be working for a federal government that could treat its citizens so unjustly.” She took on the assignment “to accurately record what the Japanese Americans were undergoing,” but apart from “a few photos that reached the public,” most of her work didn’t see the light of day for decades.

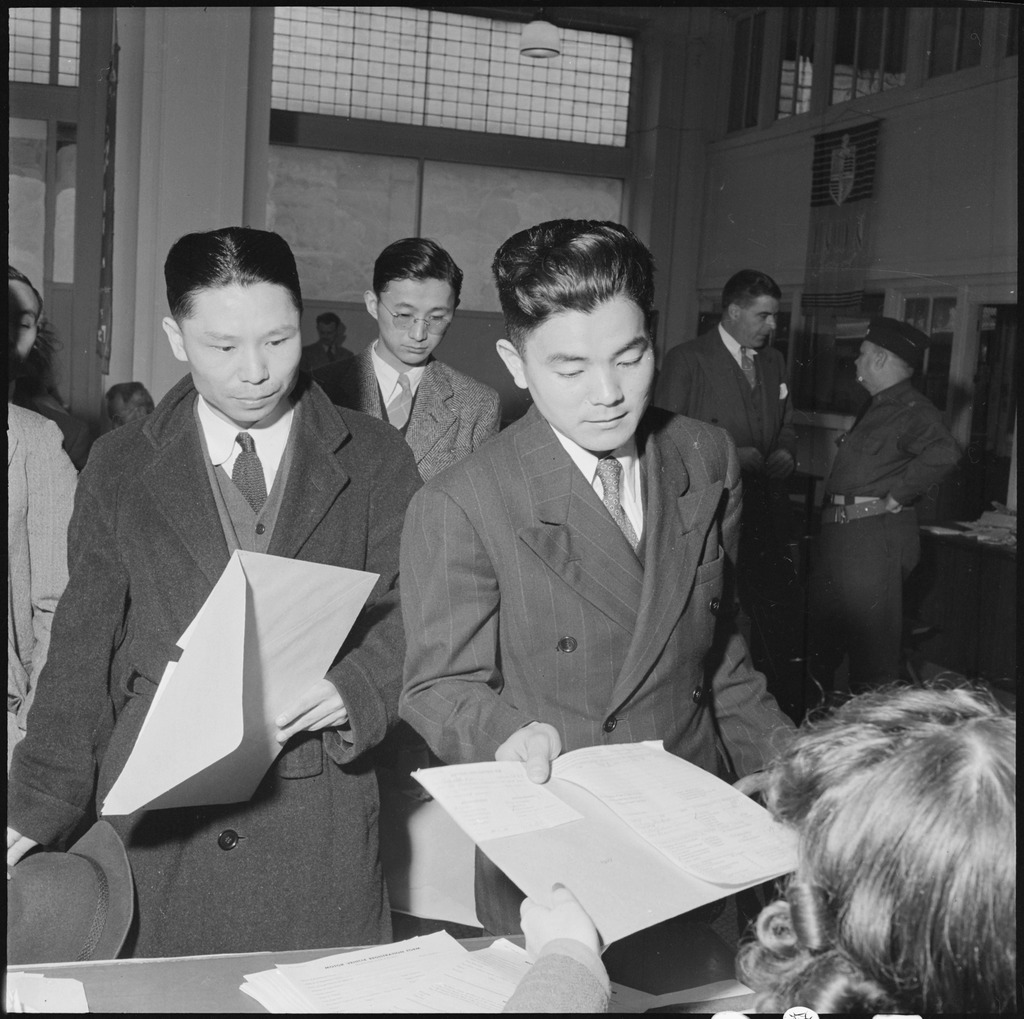

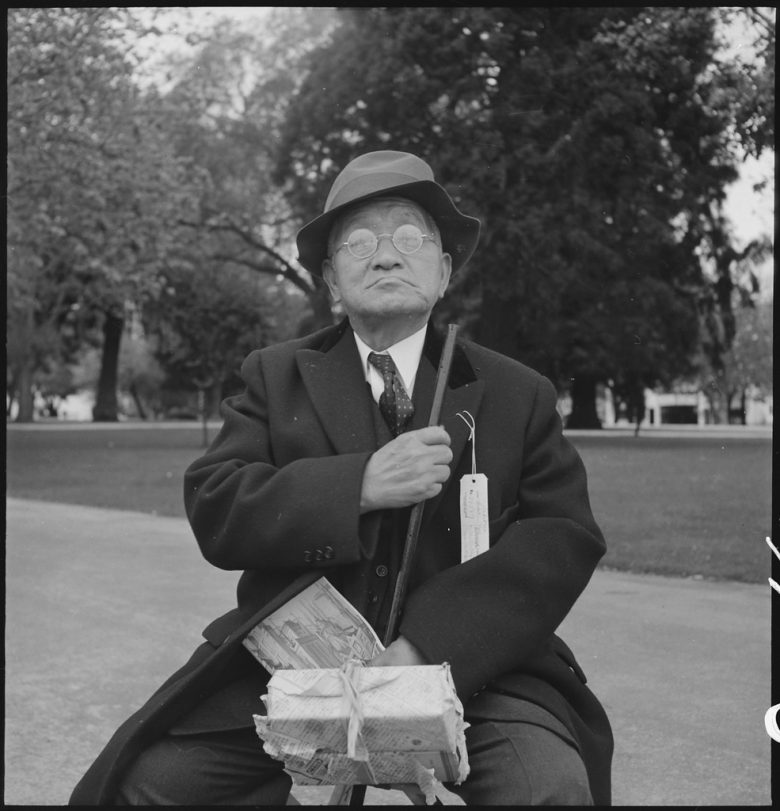

“What the military wanted from her,” explains historian Linda Gordon in a PBS documentary on Lange’s assignment, “was a set of photographs to illustrate that they weren’t persecuting or torturing these people who they evacuated.” Gordon, who co-edited Impounded, notes in the book that the photos “tell us that conditions in the camps were much worse than most people think.” It’s hard not to be reminded of another, more harrowing, forced removal happening a continent away as we see Lange’s images of Japanese American families forced to abandon their homes and stores, fill out registration paperwork, gather their belongings in suitcases, and board trains and buses en masse with numbered tags around their necks.

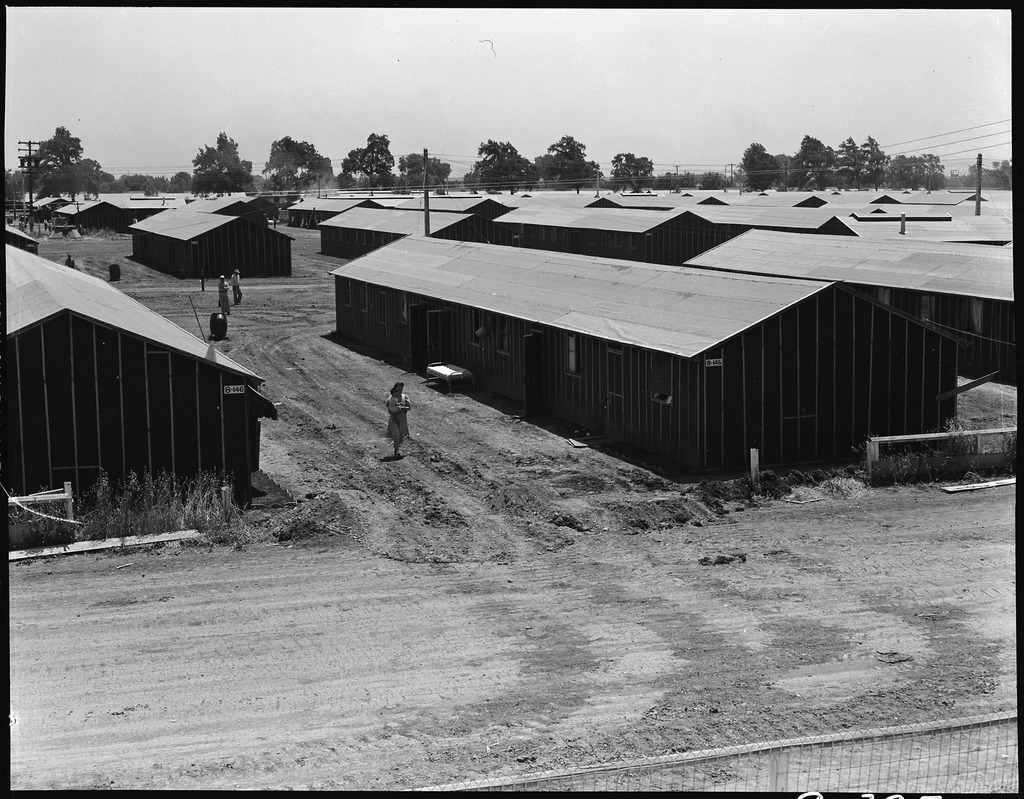

What awaited the internees at the camps were military-style barracks, libraries, rudimentary schools, and “tar-paper shacks where they endured brutal heat and bitter cold, filth, dust and open sewers,” writes Smith. Some internees were housed in former horse stalls and many endured cavity searches and other humiliating indignities, as well as daily fear and anxiety about their eventual fates. Lange’s photographs, however, “powerfully contest the government propaganda and hateful rhetoric aimed at vilifying Japanese Americans,” writes Densho: “Often shot from a low angle, Lange places her subjects on a visual pedestal. She restores some dignity in a moment when, many admit, they felt they had none.”

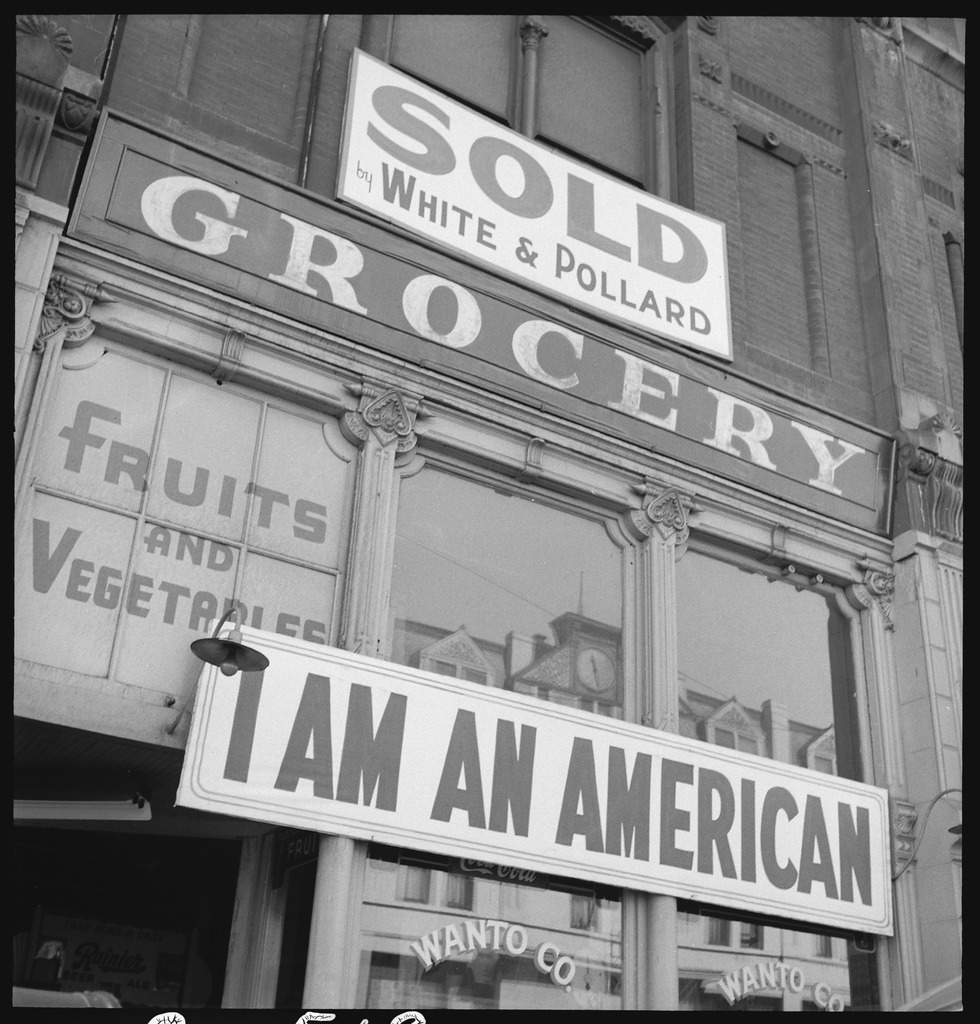

Unlike Ansel Adams’ fascinating photos, which are restricted to the confines of one camp, Lange’s document the internees entire journey from freedom to imprisonment, as well as the responses of many Japanese Americans to their new status as internal enemies of the state. One shop owner, “a University of California graduate of Japanese descent,” Lange noted, placed the sign you see above on his closed storefront.

All of the photographs in the Densho archive are now in the public domain and can be freely used for any purpose. Lange, I imagine, would hope they force us to reflect on the futile insanity of demonizing entire populations and turning on fellow citizens in times of war, xenophobic fervor and political opportunism.

via Kottke

Related Content:

200 Ansel Adams Photographs Expose the Rigors of Life in Japanese Internment Camps During WW II

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

My sister has written an award winning film script about this called , “Loyal Americans > s. She is looking for producers /backers . If interested contact me @ po*******@*ol.com Thnx , Christine Rubin

hrttdhthhyrr

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niihau_incident