From the figureheads of ships to cigar store statues to the caricature mascots of various sports teams…. Unfortunate or denigrating images of Native American peoples have persisted in popular culture, folk symbols of what Elisabeth W. Russell refers to in her history of the cigar store Indian as “The Vanishing American.” The phrase comes from the title of a Zane Grey novel, which then became a 1925 silent film dealing, wrote the New York Times that year, “with the passing of the American Indian.” Although both the novel and film attempt to protest the treatment of Native people by the U.S. government, both underwrite a common, troubling assumption—that Native Americans, like the Buffalo and the wild Mustang, were a threatened (and threatening) separate species, whose “vanishing” from the picaresque West (as they had “vanished” from the East) was a lamentable, but perhaps unavoidable, side effect of the march of Euro-American progress.

Each symbolic memorializing of Native Americans in U.S. iconography, however solemn or offensively cartoonish, gestures toward some meager recognition of a tragic loss, while erasing the circumstances that occasioned it. Of course Native Americans didn’t vanish, but were slowly killed or hounded into poverty and dispossession, and out of sight of white America—their dress, religions, and cultures made to disappear through forced assimilation, only to reappear in romanticized images of tragically conquered, but admirably warlike, primitives.

Those images proliferated during the mid-to-late 19th century, the period of intense Western settlement and expansion and the so-called Indian Wars. “It is a given today,” writes historian Brian Dipple, “that the idea of the American Indian has been historically significant. It shaped the attitudes of those in the nineteenth century who shaped Indian policy. Indian policy—be it removal of the Eastern tribes in the 1830s, reservation isolationism beginning in the 1850s, or allotment of reservation lands and assimilation in the 1880s—cannot be understood without an awareness of the ideas behind it. Literature and the visual arts provide revealing guides to nineteenth century assumptions about the Indian.”

Native historian Vine Deloria describes the cultural situation with more incisive wit in his “Indian Manifesto,” Custer Died for Your Sins: “The American public feels most comfortable with the mythical Indians of stereotype-land who were always THERE. These Indians are fierce, they wear feathers and grunt. Most of us don’t fit this idealized figure since we grunt only when overeating, which is seldom.” By the early 20th century, “mythical Indians” had become firmly embedded in popular culture, thanks to art and entertainment like the presumably serious attempts of Zane Grey and Frederic Remington, and J.M. Barrie’s deeply unserious Peter Pan. It is in this cultural atmosphere that photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis’ huge, 20-volume ethnographic project, The North American Indian emerged.

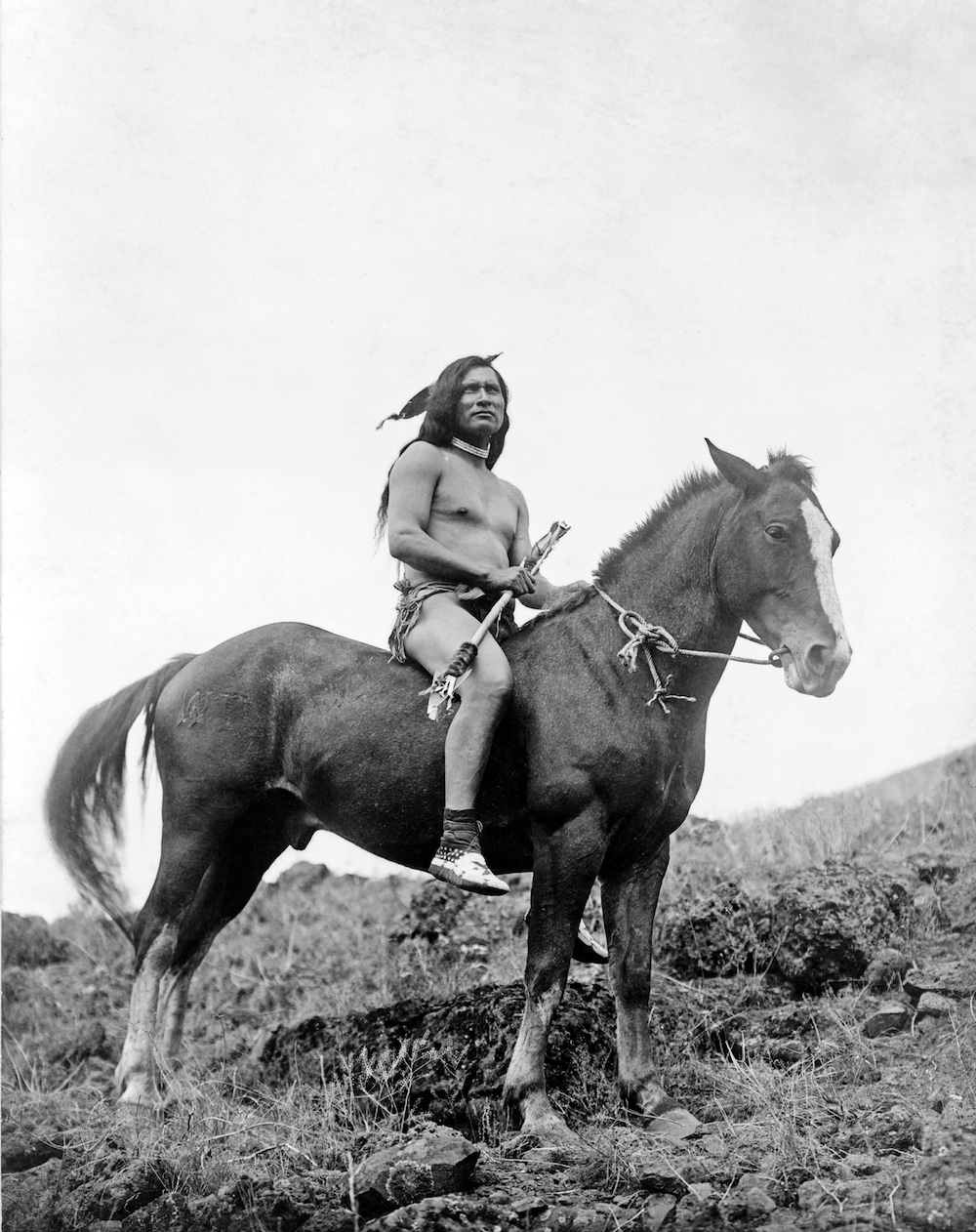

Beginning in 1904, and with the eventual backing of J.P. Morgan, writes Mashable, Curtis “spent more than 20 years crisscrossing North America, creating over 40,000 images of more than 80 different tribes. He made thousands of wax cylinder recordings of native songs and language, and wrote down oral histories, legends and biographies.” You can view and download more than 1,000 of these photographs at the Library of Congress. Curtis thought of his work as documenting “what he saw as a vanishing way of life.” Motivated by assumptions about Native people as semi-mythic remnants from the past, the photographer “sometimes meddled with the documentary authenticity of his images. He posed his subjects in romanticized settings stripped of Western civilization, more representative of an imagined pre-Colombian existence than the subjects’ actual lives in the present.”

The photographs are beautiful, their subjects ennobled by the dramatic lighting and stylized poses, and the breadth and scope of the entire project is nothing less than breathtaking. It set the stage for the significant work of later photographers and ethnographers like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and the Lomaxes. Curtis has even been credited with producing the first documentary film. The images, histories, traditions, and biographies Curtis preserved constitute an invaluable historical record. That said, we should bear in mind that The North American Indian comes to us framed by Curtis’ assumptions about Native American cultures, formed by a climate in which myth vied with, and usually supplanted, fact. What do we see in these staged images, and what do we not see?

One of Curtis’ enthusiastic early backers, Theodore Roosevelt—who authored the introduction to Volume One—was, “like many of Curtis’ eventual supporters,” writes Valerie Daniels, “more interested in obtaining a record of vanishing Native American cultures as a testament to the superiority of his own civilization than out of any concern over their situation or recognition of his own role in the process.” Though Curtis did not necessarily share these views, and later became “radical in his admonition of government policies toward Native Americans,” he also had to please his financiers and his audience, most of whom would have felt the way Roosevelt did. We should bear this cultural context in mind as we take in Curtis’ work, and ask how it shaped the creation and reception of this truly impressive record of both American history and American myth. Enter the archive of images here.

via Mashable

Related Content:

226 Ansel Adams Photographs of Great American National Parks Are Now Online

200 Ansel Adams Photographs Expose the Rigors of Life in Japanese Internment Camps During WW II

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thank you for this post!

Yes, thank you.

In HS, I read Dee Brown’s “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.” Somewhere in that book (I apologize for any errors I make in paraphrasing) were notes from a regimental commander leading one of the tribes onto a reservation. In his journal during the first few days of travel he describes them as “savages.” After a few days, and interaction with the chief, he writes, ‘I felt I was in the presence of a superior being.’ Over 3 decades later that still resonates somewhere deep inside me. Whether it was because of a simple and sudden and short-lived understanding of what is truly important or some primordial voice that speaks of concern for the “least of these” I do not know. Acculturation seems to favor those willing to pursue something more valuable to them than life and our story is still being written…

I especially enjoyed these two pictures:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b36359/?co=ecur

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a48564/?co=ecur

This little light of mine.

I am going to let it shine.

Outstanding, TY. That’s not 1000, though. Where are the rest?

Sorry, I just found the link. Don’t bother responding. Right, and THAT is outstanding! TY

i am extremly interested in the Native American Indians because for many years I have been tricked into believing that the Native indian wasthe bad guy and were seen as savages Iblame John Wayne movies.Ifeel as though I’ve been brain washed into believing they were just savages instead ofbeing the most intelligentand resourceful of natives.I was only able to understand their situation because I browsed Pinterest for pictures for my art. I am finding all information I come across very helpful for my understanding and the needs of these people Sincerely June