Phillumeny — the practice of collecting matchboxes — strikes me as a fun and practical hobby. As a child, I was fascinated with the contents of a large glass vase my grandparents had dedicated to this pursuit. Their collection was an ersatz record of all the hotels and nightclubs they had apparently visited before transforming into a dowdy older couple who enjoyed rocking in matching Bicentennial themed chairs, monitoring their bird feeder.

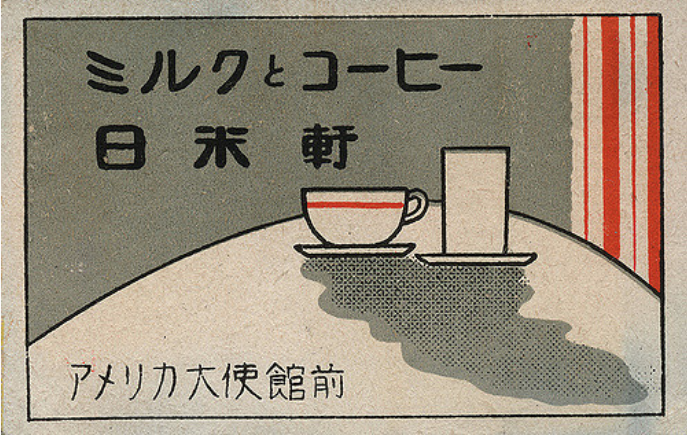

As any serious phillumenist will tell you, one need not have a personal connection to the items one is collecting. Most matchbox enthusiasts are in it for the art, a microcosm of 20th century design. The urge to preserve these disposable items is understandable, given the amount of artistry that went into them. It was good business practice for bars and restaurants to give them to customers at no charge, even if they never planned to strike so much as a single match.

Smoking’s heyday is over, but until someone figures out how to make fire with a smart phone, matchboxes and books are unlikely to disappear. Wherever you go, you’ll be able to find goodies to add to your collection, usually for free.

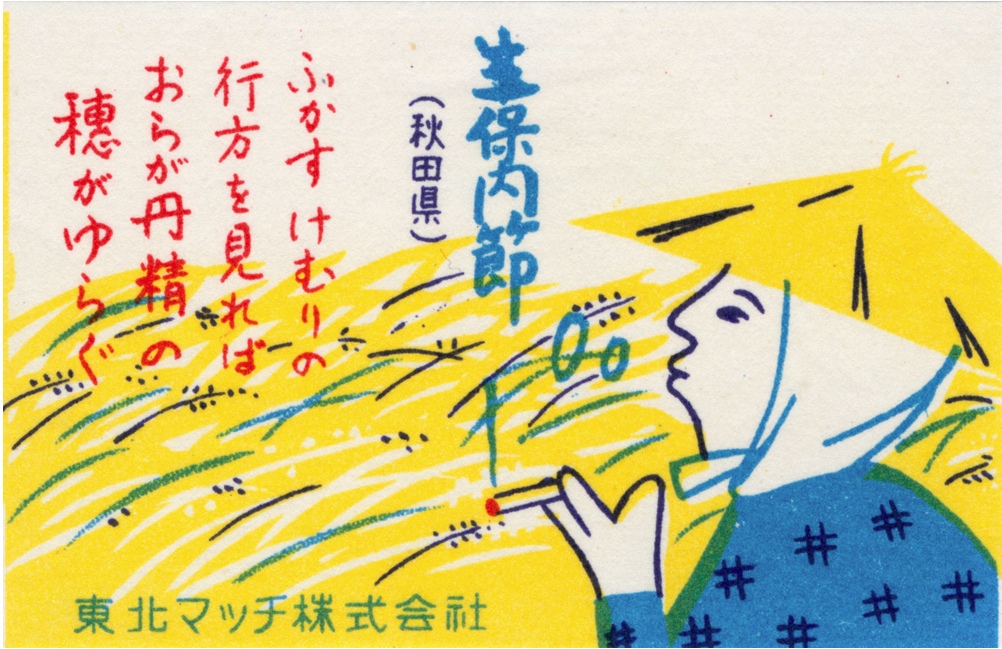

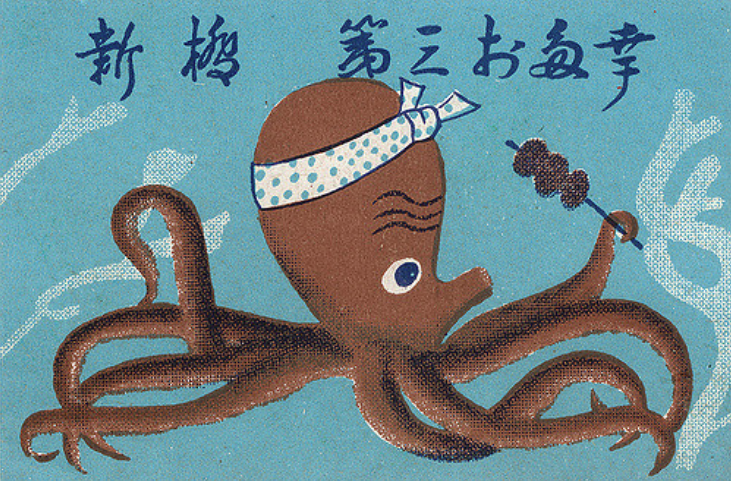

Or you could stay at home, trawling the Internet for some of the most glorious, and sought after examples of the form — those produced in Japan between the two World Wars. As author Steven Heller, co-chair of the School of Visual Arts’ MFA Design program, writes in Print magazine:

The designers were seriously influenced by imported European styles such as Victorian and Art Nouveau… (and later by Art Deco and the Bauhaus, introduced through Japanese graphic arts trade magazines, and incorporated into the design of matchbox labels during the late 1920s and ’30s). Western graphic mannerisms were harmoniously combined with traditional Japanese styles and geometries from the Meiji period (1868–1912), exemplified by both their simple and complex ornamental compositions. Since matches were a big export industry, and the Japanese dominated the markets in the United States, Australia, England, France, and even India, matchbox design exhibited a hybrid typography that wed Western and Japanese styles into an intricate mélange.

Find something that catches your eye? It shouldn’t cost more than a buck or two to acquire it, though Japanese clutter-control guru, Marie Kondo, would no doubt encourage you to adopt cartoonist Roz Chast’s approach to matchbook appreciation.

Earlier this spring, Chast shared her passion with readers of The New Yorker, collaging some of her favorites into an autobiographical comic wherein she revealed that she doesn’t collect the actual objects, just the digital images. Those familiar with Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant, Chast’s hilariously painful memoir about her difficult, aging parents’ “golden years,” will be unsurprised that she opted not to add to the unwelcome pile of “crap” that gets handed down to the next generation when a collector passes away.

If you’re inspired to start a Chast-style collection, have a rummage through the large album of Japanese vintage matchbox covers that web designer, Jane McDevitt posted to Flickr, from which the images here are drawn.

Those 418 labels, culled from a friend’s grandfather’s collection are just the tip of McDevitt’s matchbox obsession. To date, she’s posted over 2050 covers from all around the world, with the bulk hailing from Eastern Europe in the 50s and 60s. You can visit her collection of 400+ Japanese matchbox covers here. And if you’re into this stuff, check out the Japanese book, Matchbox Label Collection 1920s-40s.

Related Content:

Advertisements from Japan’s Golden Age of Art Deco

The Making of Japanese Handmade Paper: A Short Film Documents an 800-Year-Old Tradition

Ayun Halliday, author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine, will be reading from her travel memoir, No Touch Monkey! And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late at Indy Reads Books in downtown Indianapolis, Thursday, July 7. Follow her @AyunHalliday