Image by Machocarioca, via Wikimedia Commons

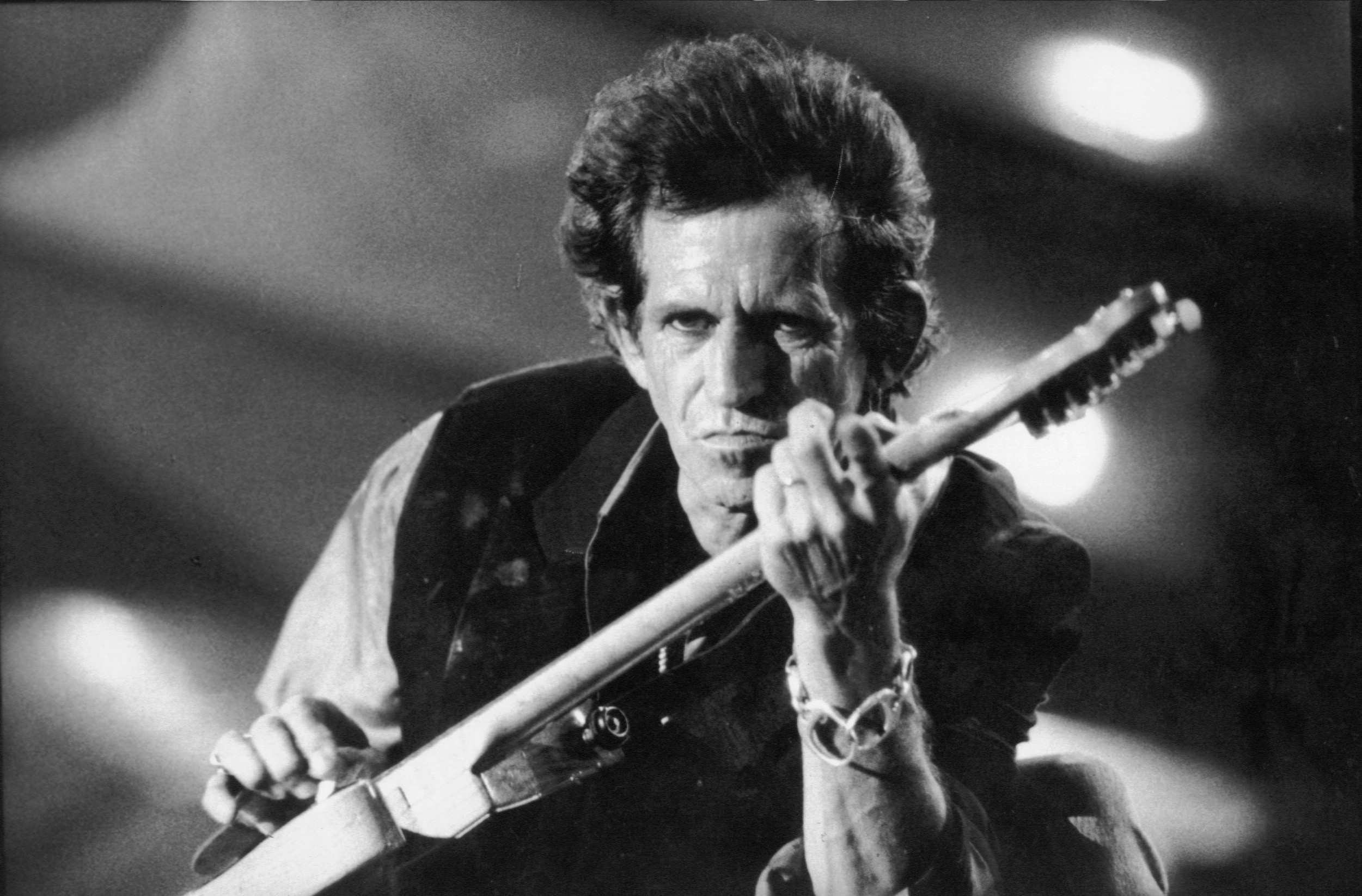

You don’t have to, like, stretch your brain or anything to rattle off a list of Keith Richards’ influences. If you’ve ever heard a Rolling Stones song, you’ve heard him pull out his Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry riffs, and he’s never been shy about supporting and naming his idols. He’s played with Waters, Berry, and many more blues and early rock and roll greats, and after borrowing heavily from them, the Stones gave back by promoting and touring with the artists who provided the raw material for their sound.

Then there’s the 2002 compilation The Devil’s Music, culled from Richards’ personal favorite collection of blues, soul, and R&B classics, and featuring big names like Robert Johnson, Little Richard, Bob Marley, Albert King, and Lead Belly, and more obscure artists like Amos Milburn, and Jackie Brenston. You may also recall last year’s Under the Influence, a Netflix documentary by 20 Feet From Stardom director Morgan Neville, in which Richards namechecks dozens of influential musicians—from his mum’s love of Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday, to his and Jagger’s youthful adoration of Waters and Berry, to his rock star hangouts with Willie Dixon and Howlin’ Wolf.

Point is, Keith Richards loves to talk about the music he loves. A big part of the Stones’ appeal—at least in their 60s/early 70s prime—was that they were such eager fans of the musicians they emulated. Yes, Jagger’s phony country drawls and blues howls could be a little embarrassing, his chicken dance a little less than soulful. But the earnestness with which the young Englishmen pursued their Americana ideals is infectious, and Richards has spread his love of U.S. roots music through every medium, including his 2010 memoir Life, a wickedly ironic title—given Richards’ No. 1 position on the “rock stars most-likely-to-die list,” writes Michiko Kakutani, “and the one life form (besides the cockroach) capable of surviving nuclear war.”

It’s also a very poignant title, given Richards’ single-minded pursuit of a life governed by music he’s loved as passionately, or more so, as the women in his life. Richards, Kakutani writes, dedicated himself “like a monk to mastering the blues.” Of this calling, he writes, “you were supposed to spend all your waking hours studying Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, Robert Johnson. That was your gig. Every other moment taken away from it was a sin.” In the course of the book, Richards mentions over 200 artists, songs, and recordings that directly inspired him early or later in life, and one enterprising reader has compiled them all, in order of appearance, in the Spotify playlist above.

You’ll find here no surprises, but if you’re a Stones fan, it’s hard to imagine you wouldn’t put this one on and listen to it straight through without skipping a single track. When it comes to blues, soul, reggae, country, and rock and roll, Keith Richards has impeccable taste. Scattered amidst the Aaron Neville, Etta James, Gram Parsons, Elvis, Wilson Pickett, etc. are plenty of classic Stones recordings that feel right at home next to their influences and peers.

With the exception of reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Sly & Robbie, most of the tracks are from U.S. or U.S.-inspired artists (Tom Jones, Cliff Richard). Again, no surprises. Not everyone Richards appropriated has appreciated the homage (Chuck Berry long held a grudge), but were it not for his fandom and apprenticeship, it’s possible a great many blues records would have gone unsold, and some artists may have faded into obscurity. Thanks to playlists like these, they can live on in a digital age that doesn’t always do so well at acknowledging or remembering its history.

Related Content:

Chuck Berry Takes Keith Richards to School, Shows Him How to Rock (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.