What kind of a blighted society turns the word “snowflake” into an insult?, I sometimes catch myself thinking, but then again, I’ve never understood why “treehugger” should offend. All irony aside, being known as a person who loves nature or resembles one of its most elegant creations should be a mark of distinction, no? At least that’s what Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley surely thought.

The Vermont farmer, self-educated naturalist, and avid photographer, was the first person to offer the following wisdom on the record, then illustrate it with hundreds upon hundreds of pictures of snowflakes, 5,000 in all:

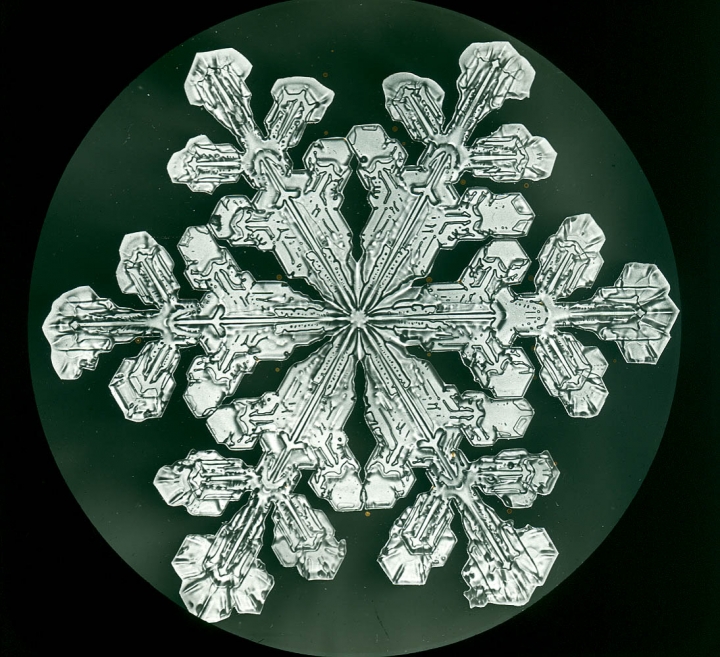

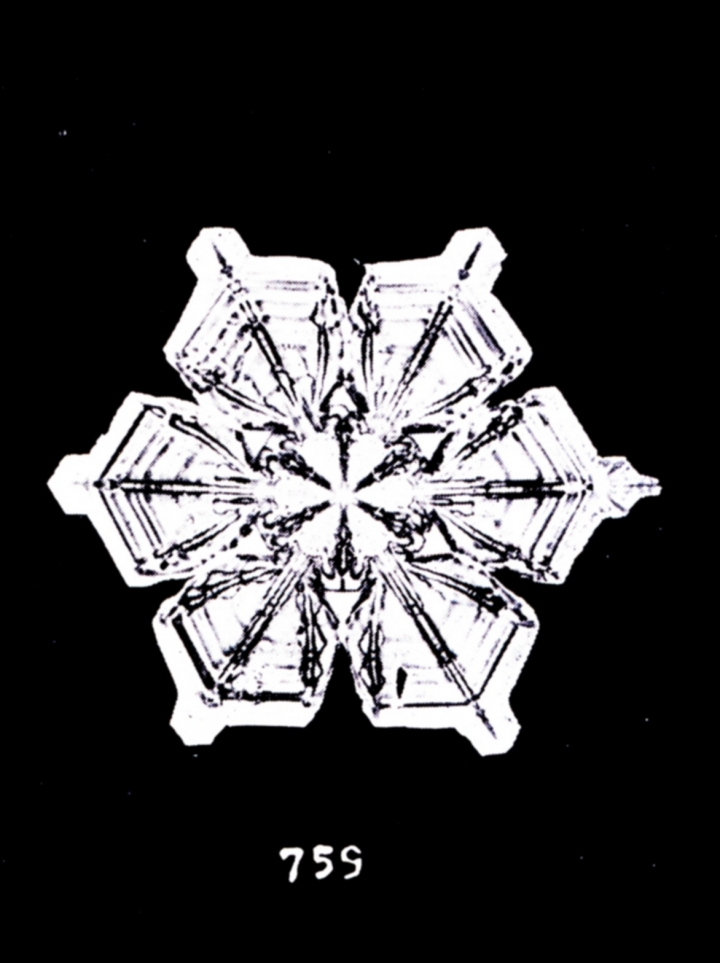

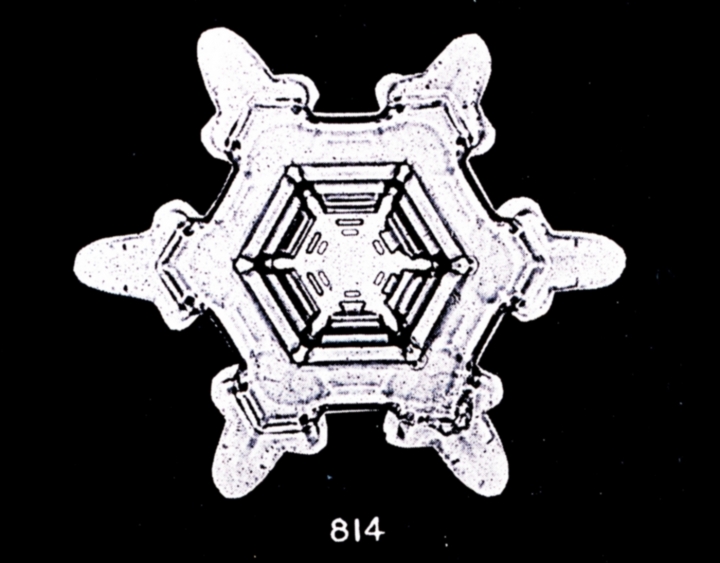

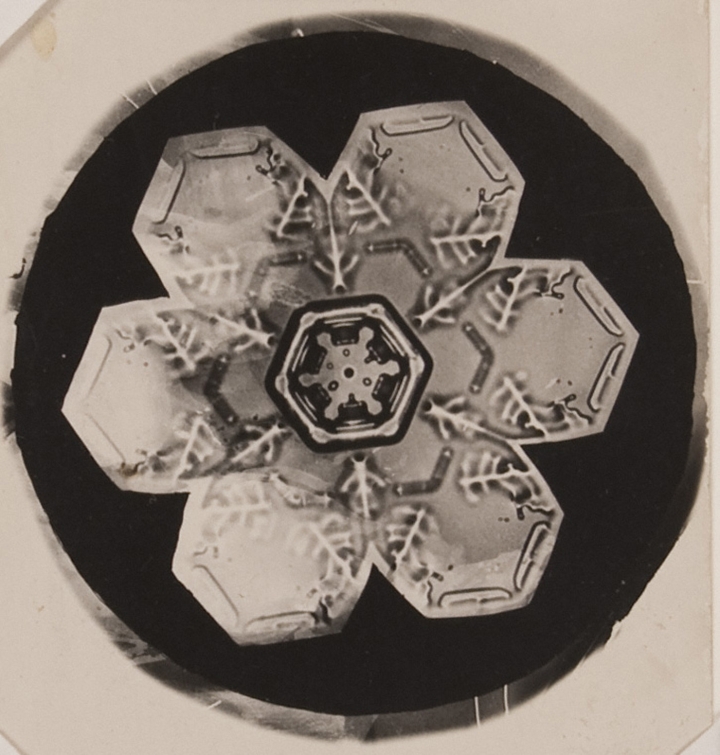

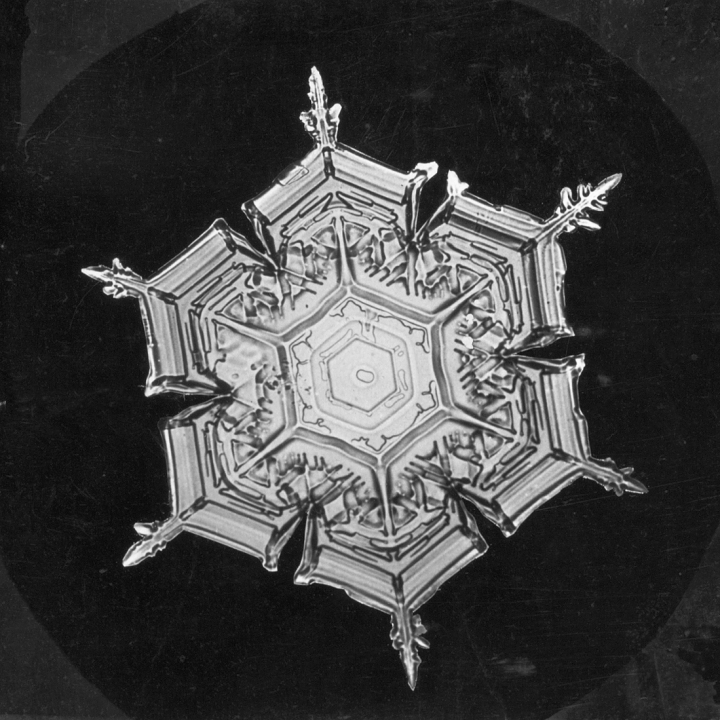

I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.

Bentley left a considerable record—though still an insignificant sample size given the scope of the object of study. But his photographs give the impression of an infinite variety of different types, each with the same basic crystalline latticework structure. He took his first photograph of a snowflake, the first ever taken, in 1885, by adapting a microscope to a bellows camera, after years of making sketches and much trial and error.

Some great portion of this work must have been tedious and frustrating—Bentley had to hold his breath for each exposure lest he destroy the photographic subject. But it was worth the effort. Bentley, the Smithsonian informs us, “was a pioneer in ‘photomicrography,’ the photographing of very small objects.” Five hundred of his photographs now reside at the Smithsonian Institution Archives, “offered by Bentley in 1903 to protect against ‘all possibility of loss and destruction, through fire or accident.” You can see a huge digital gallery of those hundreds of photos here.

Along with U.S. Weather Bureau physicist William J. Humphreys, he published 2300 of his snowflake photographs in a monograph titled Snow Crystals. Bentley also published over 60 articles on the subject (read two of them here). Despite his contributions, he receives no mention in most histories of photomicrography. This may be due to his provincial location (he never left Jericho, VT) or his lack of scientific training and credentials, or a lack of interest in photos of snowflakes on the part of most photomicrography historians.

Or it may be because Bentley was thought to be a fraud. When a German meteorologist commissioned some images of his own and got some very different results, he accused the farmer of retouching. Bentley readily admitted it, saying, “a true scientist wishes above all to have his photographs as true to nature as possible, and if retouching will help in this respect, then it is fully justified.”

The defense is a good one. Although the “nature” Bentley’s photos show us may be a theoretical idealization, so too are the hand-rendered illustrations of most scientists throughout history (and nearly every medical diagram today). Take, for example, the psychedelic, brightly colored patterns of accomplished biologist Ernst Haeckel, who turned the micro- and macroscopic world into surreally symmetrical art in his drawings. Though he might not have said so directly, Bentley was doing something similar with a camera. Just listen to him describe his process in a 1900 issue of Harper’s:

Quick, the first flakes are coming; the couriers of the coming snow storm. Open the skylight, and directly under it place the carefully prepared blackboard, on whose ebony surface the most minute form of frozen beauty may be welcome from cloud-land. The mysteries of the upper air are about to reveal themselves, if our hands are deft and our eyes quick enough.

In the “quiet frenzy of his winter’s quest,” writes Allison Meier at Hyperallergic, he produced images of “beautiful ghosts from a winter that bristled the air over a century ago.” Learn more about Bentley’s life, work, and the Smithsonian collection in the short documentary further up, the Washington Post video above, and the Radiolab episode below, in which a breathless Latif Nasser takes us into the heart of Bentley’s origin story, and “snowflake expert and photographer Ken Libbrecht helps set the record straight.”

Real snowflakes have many imperfections, and perhaps Bentley did snow a disservice to so strenuously suggest otherwise. But the record he left us, Meier notes, “is appreciated as much as an artistic archive as a meteorological one.” He might have been a scientist when it came to technique, but Bentley was a romantic when it came to snow. His story is as fascinating as his photographs. Maybe a delightful alternative to the usual Christmas fare. There’s even a children’s book called… what else?… Snowflake Bentley.

via Smithsonian/Hyperallergic

Related Content:

See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838)

The First Known Photograph of People Sharing a Beer (1843)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

the image archives (Bentley’s photos) I think moved on the Smithsonian website. I found some here (11/25/19)

https://siarchives.si.edu/history/featured-topics/stories/wilson-bentley-pioneering-photographer-snowflakes/image-gallery-snowflakes

I don’t know if this covers all 500 images but the link provided in the original article seems like it is out of date

the snow flakes were ok