When did language begin? The question is not an easy one to answer. There are no records of the event. “Languages don’t leave fossils,” notes the Linguistic Society of America, “and fossil skulls only tell us the overall shape and size of hominid brains, not what the brains could do.” The scant evidence from evolutionary biology does not tell us when early humans first began to use language, only that they could 100,000 years or so ago.

However, the question also depends on what we mean by language. Before the linguistic technologies of grammar and syntax, hominids, like other mammals today and a good number of non-mammals too, had a wordless language that communicated more directly, and more honestly, than any of the thousands of ways to string syllables into sentences.

That language still exists, of course, and those who understand it know when someone is afraid, relieved, frustrated, angry, confused, surprised, embarrassed, or awed, no matter what that someone says. It is a language of feeling—of sighs, grunts, rumbles, moans, whistles, sniffs, laughs, sobs, and so forth. Researchers call them “vocal bursts” and as any long-suffering married couple can tell you, they communicate a whole range of specific feelings.

“Emotional expressions,” says UC Berkeley psychology graduate student Alan Cowen, “color our social interactions with spirited declarations of our inner feeling that are difficult to fake, and that our friends, co-workers and loved ones rely on to decipher our true commitments.“ Cowen and his colleagues devised a study to test the range of emotion vocal bursts can carry.

The researchers asked 56 people, reports Discover magazine, “some professional actors and some not, to react to different emotional scenarios” in recordings. Next, they played the recordings for over a 1,000 people, who rated “the vocalizations based on the emotions and tone (positive or negative) they thought the clips conveyed.”

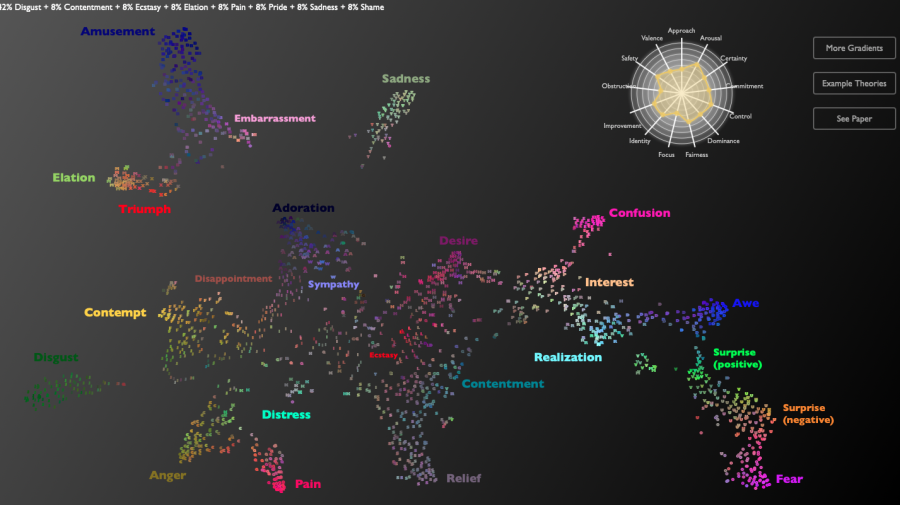

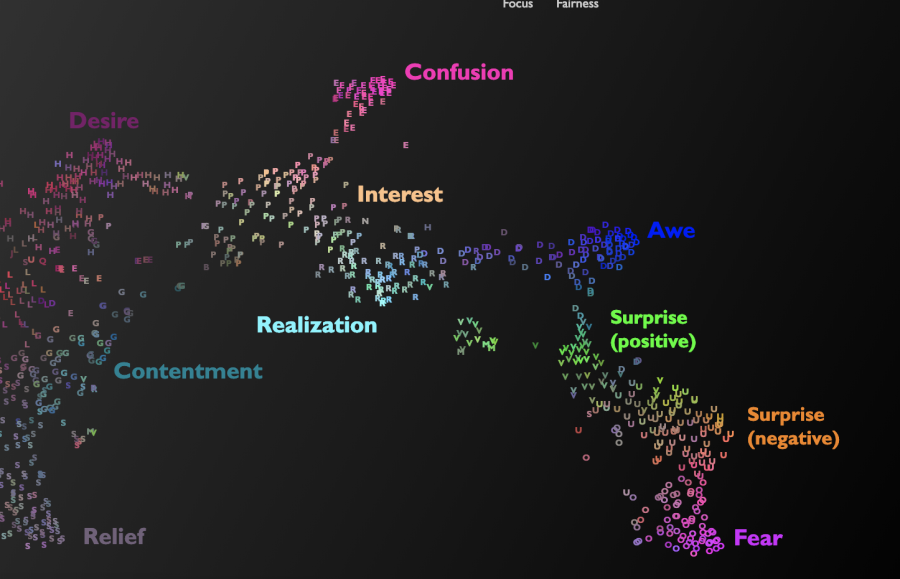

The researchers found that “vocal bursts convey at least 24 distinct kinds of emotions.” They plotted those feelings on a colorful interactive map, publicly available online. “The team says it could be useful in helping robotic devices better pin down human emotions,” Discover writes. “It could also be handy in clinical settings, helping patients who struggle with emotional processing.” The study only recorded vocalizations from English speakers, and “the results would undoubtedly vary if people from other countries or who spoke other languages were surveyed.”

But this limitation does not undermine another implication of the study: that human language consists of far more than just words, and that vocal bursts, which we likely share with a wide swath of the animal kingdom, are not only, perhaps, an original language but also one that continues to communicate the things we can’t or won’t say to each other. Read the study here and see the interactive vocal burst map here.

via MetaFilter

Related Content:

Where Did the English Language Come From?: An Animated Introduction

Why We Say “OK”: The History of the Most Widely Spoken Word in the World

The History of the English Language in Ten Animated Minutes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

So, my discovery has been leaked out, heh !? you smelly rats !