Is the singularity upon us? AI seems poised to replace everyone, even artists whose work can seem like an inviolably human industry. Or maybe not. Nick Cave’s poignant answer to a fan question might persuade you a machine will never write a great song, though it might master all the moves to write a good one. An AI-written novel did almost win a Japanese literary award. A suitably impressive feat, even if much of the authorship should be attributed to the program’s human designers.

But what about literary criticism? Is this an art that a machine can do convincingly? The answer may depend on whether you consider it an art at all. For those who do, no artificial intelligence will ever properly develop the theory of mind needed for subtle, even moving, interpretations. On the other hand, one group of researchers has succeeded in using “sophisticated computing power, natural language processing, and reams of digitized text,” writes Atlantic editor Adrienne LaFrance, “to map the narrative patterns in a huge corpus of literature.” The name of their literary criticism machine? The Hedonometer.

We can treat this as an exercise in compiling data, but it’s arguable that the results are on par with work from the comparative mythology school of James Frazier and Joseph Campbell. A more immediate comparison might be to the very deft, if not particularly subtle, Kurt Vonnegut, who—before he wrote novels like Slaughterhouse Five and Cat’s Cradle—submitted a master’s thesis in anthropology to the University of Chicago. His project did the same thing as the machine, 35 years earlier, though he may not have had the wherewithal to read “1,737 English-language works of fiction between 10,000 and 200,000 words long” while struggling to finish his graduate program. (His thesis, by the way, was rejected.)

Those numbers describe the dataset from Project Gutenberg fed into the The Hedonometer by the computer scientists at the University of Vermont and the University of Adelaide. After the computer finished “reading,” it then plotted “the emotional trajectory” of all of the stories using a “sentiment analysis to generate an emotional arc for each work.” What it found were six broad categories of story, listed below:

- Rags to Riches (rise)

- Riches to Rags (fall)

- Man in a Hole (fall then rise)

- Icarus (rise then fall)

- Cinderella (rise then fall then rise)

- Oedipus (fall then rise then fall)

How does this endeavor compare with Vonnegut’s project? (See him present the theory below.) The novelist used more or less the same methodology, in human form, to come up with eight universal story arcs or “shapes of stories.” Vonnegut himself left out the Rags to Riches category; he called it an anomaly, though he did have a heading for the same rising-only story arc—the Creation Story—which he deemed an uncommon shape for Western fiction. He did include the Cinderella arc, and was pleased by his discovery that its shape mirrored the New Testament arc, which he also included in his schema, an act the AI surely would have judged redundant.

Contra Vonnegut, the AI found that one-fifth of all the works it analyzed were Rags-to-Riches stories. It determined that this arc was far less popular with readers than “Oedipus,” “Man in a Hole,” and “Cinderella.” Its analysis does get much more granular, and to allay our suspicions, the researchers promise they did not control the outcome of the experiment. “We’re not imposing a set of shapes,” says lead author Andy Reagan, Ph.D. candidate in mathematics at the University of Vermont. “Rather: the math and machine learning have identified them.”

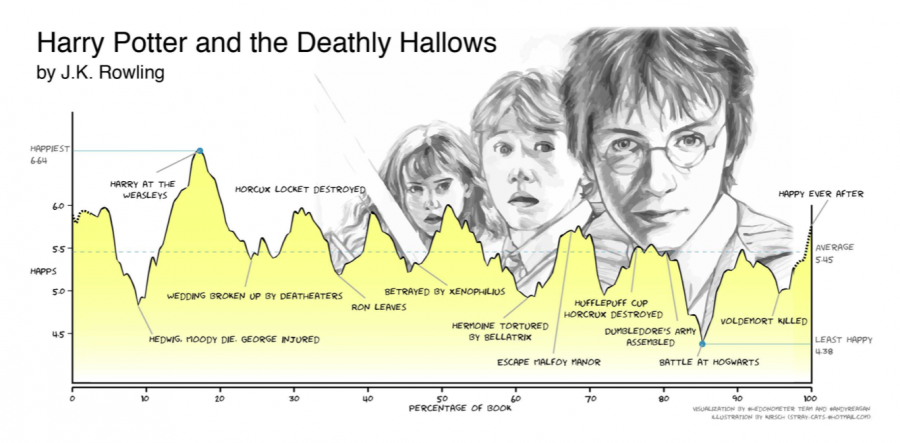

But the authors do provide a lot of their own interpretation of the data, from choosing representative texts—like Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows—to illustrate “nested and complicated” plot arcs, to providing the guiding assumptions of the exercise. One of those assumptions, unsurprisingly given the authors’ fields of interest, is that math and language are interchangeable. “Stories are encoded in art, language, and even in the mathematics of physics,” they write in the introduction to their paper, published on Arxiv.org.

“We use equations,” they go on, “to represent both simple and complicated functions that describe our observations of the real world.” If we accept the premise that sentences and integers and lines of code are telling the same stories, then maybe there isn’t as much difference between humans and machines as we would like to think.

via The Atlantic

Related Content:

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

Kurt Vonnegut Maps Out the Universal Shapes of Our Favorite Stories

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Curious as to what Hal would think about this.

@VLH “What the Hal?”

It seems solipsistic to imagine being moved to feel by a robotic creation.

The twist here: this article was written by a machine! ;-p

Isn’t HAL the idiom (name) given the spaceship computer in 2001 Space Odyssey instead of IBM (each letter one previous) to avoid legal problems?

Research crystal energy and frequencies — XS4ALL

Are there any questions which AI cannot answer: example, humans’ articulations are the limbs and the movements of the limbs.

It is true that male and female have grown together on the planet earth for as long as bi-pedal kife has existed. These movements in the circumference of all turns, these range of motions in contrast with all other objects is how the tines of alphabets have come into human existence for the use of language… to question the rationality of intelligence in contrast with the speed of cognition the artificial intelligence as humans integrate all the turning through space and time, space and time hold the keys to existence, and artificial intelligence is constructed and comprised of atoms, human biology, human anatomical biology, constructs of polarity, et cetera… Jordan Peterson Explains Psychoanalytic Theory

Will artificial intelligence be capable of accomplishing faster than light travel???????????????????????????????

Alpha Particles and the Atom — Niels Bohr Library & Archives

Language is embedded within existence by and because of polairit/time…

|

The Capture of Electrons by Alpha-Particles

|

Quantum Mechanics: Schrödinger’s discovery of the shape of atoms

Why are words constructed of syllables transcribed with polarity crystalline in content, YowYow

Transvestigation Transpocalypse Gender Inversion Kaia Gerber Cindy Crawford Clone

The Symbolosphere, Conceptualiztion, Language and Neo-Dualism

Endosymbiotic Theory