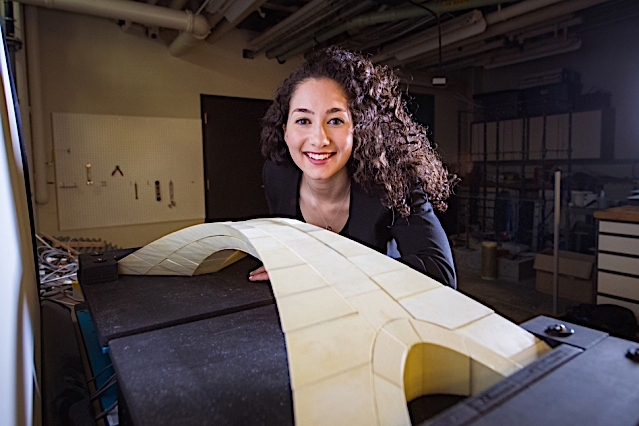

Photo by Gretchen Ertl, via MIT News

Unfortunate though it may be for the dreamers of the world, we’re all judged not by what we imagine, but what we actually do. This goes double for those specifically tasked with creating things in the physical environment, from engineers and architects to inventors and artists. Leonardo da Vinci, the original “Renaissance man,” was an engineer, architect, inventor, artist, and more besides, and five centuries after his death we continue to admire him for not just the works of art and technology he realized during his lifetime, but also the ones that never made it off his drawing board (or out of his notebooks). And as we continue to discover, many of the latter weren’t just flights of fancy, but genuine innovations grounded in reality.

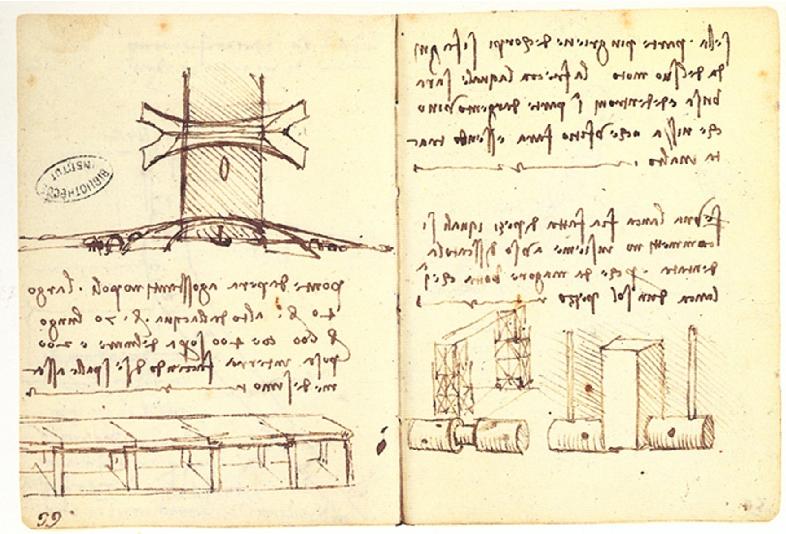

Take the bridge Leonardo proposed to Sultan Bayezid II, who in 1502 had “sent out the Renaissance equivalent of a government RFP (request for proposals), seeking a design for a bridge to connect Istanbul with its neighbor city Galata,” writes MIT News’ David L. Chandler. Writing to the sultan, Leonardo describes his design as “a masonry bridge as high as a building, and even tall ships will be able to sail under it.”

At the time, such bridges required the support of piers all along their spans, which prevented large ships from passing underneath. But Leonardo’s design would do the job with only “a single enormous arch.” About ten times longer than the typical bridge of the early 16th century, it took a page from the bridges of ancient Rome, designed as it was to “stand on its own under the force of gravity, without any fasteners or mortar to hold the stone together.”

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Alas, Leonardo, who had better luck with Italian patrons, didn’t win this particular commission. His bridge design must at least have impressed the sultan with its sheer ambition, but would it have held up? A team at MIT consisting of graduate Karly Bast, professor John Ochsendorf, and undergraduate Michelle Xie recently put it to the test, scrutinizing the material Leonardo left behind, replicating the geological conditions of the proposed site, and building a 1:500 scale model out of 126 3D-printed blocks. Not only could the model bear weight using only the strength of its own geometry, the design also came with other features, such as stabilizing abutments (which Chandler compares to the legs of “a standing subway rider widening her stance to balance in a swaying car”) to keep the bridge upright in that earthquake-prone area of modern-day Turkey.

That particular location didn’t get a bridge until 1845, when Valide Sultan ordered the construction of the first, wooden, Galata Bridge. It stood for 18 years until its replacement by another wooden bridge, part of an infrastructure-building push before Napoleon III’s visit to Istanbul. The third Galata Bridge, completed in 1875 from a design by a British engineering firm, floated on pontoons. The fourth was a German-designed floating bridge in use from 1912 until a fire damaged it in 1992. Only the fifth and current Galata Bridge, with its tram tracks above, its pedestrianized deck full of shops and market spaces below, and it drawbridge section in the middle, was built by a Turkish company. In all its iterations, the Galata Bridge has become one of Istanbul’s cultural reference points and major attractions as well — not that having been designed by Leonardo would have hurt its image any.

via MIT News/Popular Mechanics

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More

An Animated History Of Aviation: From Leonardo da Vinci’s Sketches to Apollo 11

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Fascinating, but the bridge, if built, would have been almost 500m long. This would have entailed (to judge from the photo above) a truly enormous structure. While it seems ergonomic and effective, it probably would not have suited contemporary aesthetics.