In these times, we need to keep at some kind of routine. And so I’d like to doff my cloth worker’s cap to Denis Shiryaev, who once again has returned from the early days of cinema with another AI-restored clip of film from the early 20th century.

Ah, but there’s something amiss this time, a glitch in the matrix of expectations. Not all sources can be saved by technology. Fans of Shiryaev’s crystal clear journeys back in time (find them in the Relateds below) might find the footage rough. It doesn’t make this film any less fascinating.

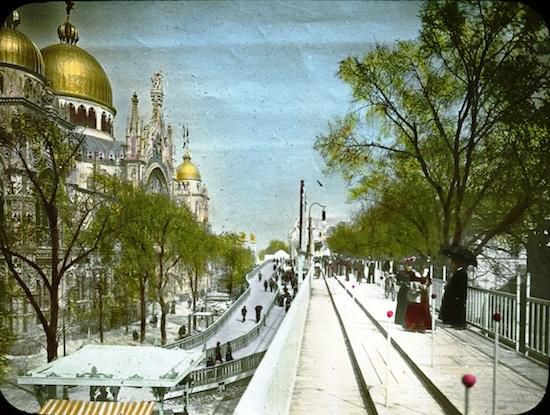

Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon started their film business to try to copy the success of similar, earlier filmmakers like the Lumiere Brothers in Paris. Audiences would pay to see short films of how people lived, worked, walked about, and just existed. It was a window into another reality, and by pure chance a hundred of Mitchell & Kenyon’s films were found preserved in a Blackburn, UK basement nearly a century later. This is a compilation of three of them, scored by Guy Jones with mild atmospherics.

More than any of the other films that Shiryaev has “restored,” Mitchell & Kenyon don’t try to hide their camera or pretend it’s not there. Instead, these three films make a point of inviting their subjects to look directly at us, and because of Shiryaev’s work these dozens and dozens of eyes really seem to be watching us from across time. The young boys are cheeky, the young girls shy, the older adults bemused or slightly irritated. There is no particular focus here–we can choose who we want to follow, which indeed was one of the reasons for these films popularity. They were designed for repeat visits.

There are two particular points of interest that happen very quickly. One is at 1:09–the appearance of an Afro-Caribbean man as part of the workforce. People of African descent had lived in Britain since the 12th century, but this might be one of the earliest films of such a person. The other is later at 4:24, which might be the first film of a bloke giving the camera the rude two-fingered salute. This moment is why the British Film Institute dubbed Mitchell & Kenyon “the accidental anthropologists.”

(You might also watch for the fight that breaks out near the end of the film. Real or not? You be the judge.)

Related Content:

Watch Scenes from Czarist Moscow Vividly Restored with Artificial Intelligence (May 1896)

Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.