|

|

Finally, we leave you with this — Mailer reading from his new work, describing the conception of Hitler, as told from the devil’s perspective, in somewhat racy terms. (NOTE: the video quality is very Youtube-esque, but it gets the job done): |

Norman Mailer’s Fuhrer in MultiMedia

The Art of Reading a Poem (According to Harold Bloom)

Most university podcasts allow the outside world to listen in on fairly polished and formal campus lectures. But this podcast is different. As part of its new iTunes initiative, Yale University has recently released a recording of famed literary critic Harold Bloom (see bio) teaching a seminar on “The Art of Reading a Poem” (listen above). Here, Bloom endearingly takes his students through a poem by Wallace Stevens, Parts of a World, and constantly moves between interpretation and digression — digressions that are often filled with intriguing personal anecdotes (as well as frequent laments for other thinkers from Bloom’s generation who have since passed away).

The podcast is notable for being remarkably unedited, which has its pluses and minuses. On the downside, the seminar doesn’t really get going until 13 minutes in (so consider starting there), and the first few minutes include a long stretch of silence when Bloom excuses himself from the room. On the upside, the unedited cut creates a kind of cinéma vérité experience for the listener. You get to hear Bloom, one of America’s best literary critics, working in the classroom in an unadulterated way, teasing apart a poem by one of America’s best poets. There is something immediate, pure and exciting about this way of using the podcast, an approach that universities should look at more closely.

See more University Podcasts here.

Philip Roth’s Everyman and Beyond

Courtesy of the radio program Open Source, we get an intriguing and wideranging interview with Philip

Roth, where he talks candidly about his latest and 27th novel Everyman, a work that takes an existentially anguishing look at the end of life. We also get Roth reading from other past novels, talking about the day-to-day practice of writing, and offering thoughts on the current state of American politics. You can catch the interview in one of three ways: iTunes, Rss feed, mp3 stream.

For other interviews with prominent thinkers, see our page called Smart Talks — Leading Thinkers in Multi-Media.

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Let’s go into Christmas on the right note, with a free podcast of Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol. (Find it here on iTunes.) Written in 1843, Dicken’s tale remains one of the most popular Christmas stories of all time. It gave us the indelible characters of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, and the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future. And it invented the notion of “christmas spirit.” This podcast is rather well read. If you’d like to read along with the actual text, you can get a free etext here, courtesy of Project Gutenberg.

Also, you can find other free Christmas stories at Librivox. On this page, you can stream mp3s of many different holiday tales.

For more free audio books, check out our Audio Book Podcast Collection. We now have over 40 classics listed and ready to download. Happy holidays.

Google’s Shakespeare

Google has always shied away from the content creation business. While Yahoo spent precious resources developing expensive content, the Google folks contented themselves with developing technology that organized the rest of the world’s information. And it paid off well. Given this approach, it was somewhat strange to stumble upon an editorialized part of their web site that invites users to “Explore Shakespeare with Google.” But we’re glad we did.

Google’s Shakespeare product is part of the company’s larger Book Search initiative, which, to boil it down, involves scanning millions of books, putting them on Google’s servers, and allowing users to search the print universe like they do the world of web content. Although some aspects of the project have proven to be highly controversial (namely, the decision to scan millions of copyrighted texts), other aspects have been easily welcomed by the publishing community. This includes the decision to scan and archive a panoply of old, public domain texts.

This is where we get to Google’s Shakespeare. What you’ll find here is a collection of all of the Bard’s plays in full text. The histories, tragedies, comedies, romances — they are all here. The folks at Googleplex give you the ability to access each play in its entirety and peruse it online. Or, alternatively, you can download each play as a PDF file, which gives you the ability to print the text and work through it in new ways. This kind of editorial collection is hard to argue with. In fact, we’d like to see more collections like it. But something tells us that this isn’t likely — that the Bard (oh, and China) is just about the only thing for which Google will make an exception.

Coltrane Spotify Sample

Third

America lost more than it realized today. Styron was, of course, appreciated by a great number of writers, readers, and critics. But, these days, he isn’t usually mentioned in the same sentence as Philip Roth, John Updike, or Norman Mailer, the elder statesmen of contemporary American literature. There are some legitimate reasons for that. Reputation is often simply a function of output and, since 1993, Styron hadn’t published anything new. He was then dealing with serious depression, which he wrote eloquently about in one of his last works, Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness, and he would be in and out of hospitals from there.

We’re hoping to rely on our loyal readers rather than erratic ads. To support Open Culture’s educational mission, please consider making a donation. We accept PayPal, Venmo (@openculture), Patreon and Crypto! Please find all options here. We thank you! ![]()

The 10 Best Books of the Year

Last week, The New York Times’ Book Review published its list, 100 Notable Books of the Year and it has since followed up with a whittled down list, The 10 Best Books of 2006. It’s boiled down to 5 works of fiction, and 5 non-fiction, and here’s what it looks like:

FICTION

ABSURDISTAN — Gary Shteyngart

THE COLLECTED STORIES OF AMY HEMPEL — Amy Hempel

THE EMPEROR’S CHILDREN — Claire Messud

THE LAY OF THE LAND — Richard Ford

SPECIAL TOPICS IN CALAMITY PHYSICS — Marisha Pessl

NONFICTION

FALLING THROUGH THE EARTH: A Memoir — Danielle Trussoni

THE LOOMING TOWER: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. — Lawrence Wright.

MAYFLOWER: A Story of Courage, Community, and War — Nathaniel Philbrick

THE OMNIVORE’S DILEMMA: A Natural History of Four Meals — Michael Pollan

THE PLACES IN BETWEEN — Rory Stewart

(Note: This list won’t appear in print until the December 10th.)

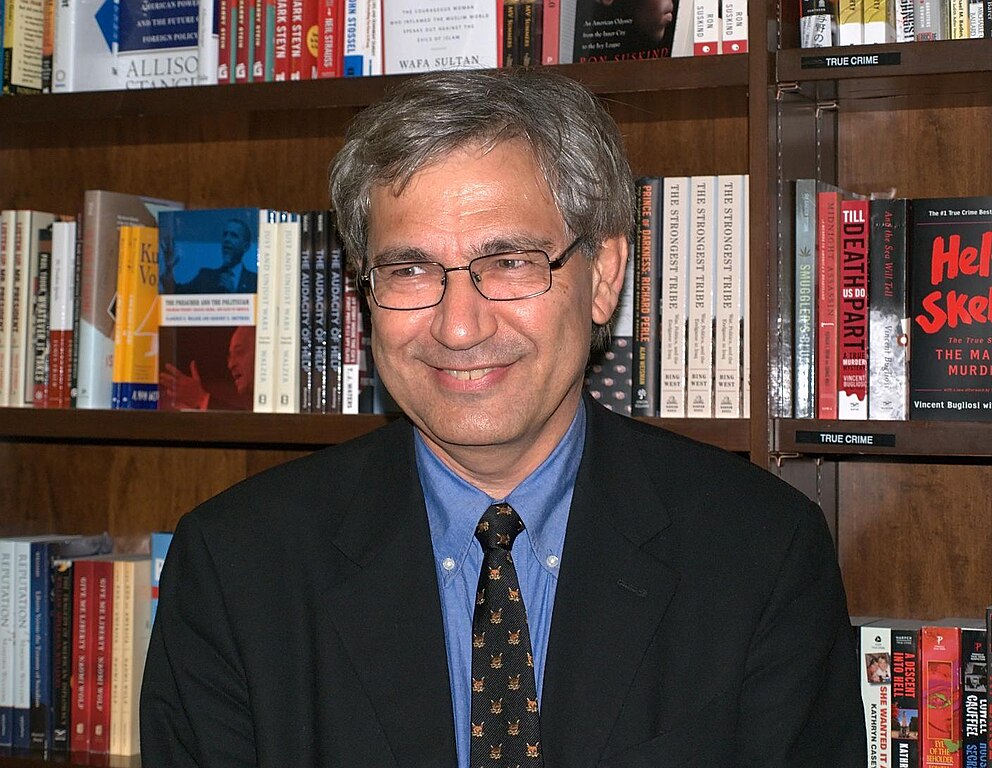

The Nobel Prize in Literature: Who is Orhan Pamuk?

Image by David Shankbone, via Wikimedia Commons

We now know the list of Nobel Prize winners for 2006, and the award ceremony in Stockholm is not far off (December 10th). This year’s prize in literature went to Orhan Pamuk, who is almost a rock star in his home country, Turkey, but less well known outside. But that’s clearly about to change. If you’re not already familiar with Pamuk’s work, we’ve pulled together some resources for you. Born in Istanbul in 1952 (check out the Nobel bio here), Pamuk has written 10 books in Turkish — of which 7 have been translated into English — and, through complex plots and post-modern devices, his books repeatedly come back to exploring a duality — the relationship between East and West, Islamic values and Western values, religion and secularism. As John Updike puts it in a review of Snow, a particularly acclaimed work, what Pamuk delivers is an artistic look at “the tension between the secularism established by Kemal Atatürk in the nineteen-twenties and the recent rise of political Islam; … the cultural divide between a Westernized élite and the theistic masses.”

Much to his chagrin, Pamuk has gained public stature not simply because of his literary achievements, but because he has taken strong public stands against the repressive tendencies of his government and Islamic radicalism more generally. And he has paid a personal price. Notably, he was the first writer in the Muslim world to denounce the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. Also, when he declared in a 2005 interview that “Thirty thousand Kurds and a million Armenians were killed in these lands [Turkey between 1915 and 1917] and nobody dares to talk about it,” the Turkish government responded by harrassing him and then bringing him up on charges — charges it was eventually forced to drop because of international pressure. As this interview makes clear, Pamuk is not exactly what you’d call an eager dissident. Rather, you get the strong sense that it’s a moral obligation for him, the ethical cost of being famous in a country that has too few people willing to call on the government to account for its actions.

Resources:

Text

- Pamuk on “The Freedom to Write”

- Pamuk’s Short Personal Piece in The New Yorker

- A Conversation with Orhan Pamuk

- Guardian Profile

Media

- Orhan Pamuk Interview: Nobel Prize Winner 2006 (Real Player — Audio)

- Pamuk on his novel, “Snow” (Online Stream)