Fellini’s Fantastic TV Commercials for Barilla, Campari & More: The Italian Filmmaker Was Born 100 Years Ago Today

To help celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of the great Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini, we present a series of lyrical television advertisements made during the final decade of his life.

In 1984, when he was 64 years old, Fellini agreed to make a miniature film featuring Campari, the famous Italian apéritif. The result, Oh, che bel paesaggio! (“Oh, what a beautiful landscape!”), shown above, features a man and a woman seated across from one another on a long-distance train.

The man (played by Victor Poletti) smiles, but the woman (Silvia Dionisio) averts her eyes, staring sullenly out the window and picking up a remote control to switch the scenery. She grows increasingly exasperated as a sequence of desert and medieval landscapes pass by. Still smiling, the man takes the remote control, clicks it, and the beautiful Campo di Miracoli (“Field of Miracles”) of Pisa appears in the window, embellished by a towering bottle of Campari.

“In just one minute,” writes Tullio Kezich in Federico Fellini: His Life and Work, “Fellini gives us a chapter of the story of the battle between men and women, and makes reference to the neurosis of TV, insinuates that we’re disparaging the miraculous gifts of nature and history, and offers the hope that there might be a screen that will bring the joy back. The little tale is as quick as a train and has a remarkably light touch.”

Also in 1984, Fellini made a commercial titled Alta Societa (“High Society”) for Barilla rigatoni pasta (above). As with the Campari commercial, Fellini wrote the script himself and collaborated with cinematographer Ennio Guarnieri and musical director Nicola Piovani. The couple in the restaurant were played by Greta Vaian and Maurizio Mauri. The Barilla spot is perhaps the least inspired of Fellini’s commercials. Better things were yet to come.

In 1991 Fellini made a series of three commercials for the Bank of Rome called Che Brutte Notti or “The Bad Nights.” “These commercials, aired the following year,” writes Peter Bondanella in The Films of Federico Fellini, “are particularly interesting, since they find their inspiration in various dreams Fellini had sketched out in his dream notebooks during his career.”

In the episode above, titled “The Picnic Lunch Dream,” the classic damsel-in-distress scenario is turned upside down when a man (played by Paolo Villaggio) finds himself trapped on the railroad tracks with a train bearing down on him while the beautiful woman he was dining with (Anna Falchi) climbs out of reach and taunts him. But it’s all a dream, which the man tells to his psychoanalyst (Fernando Rey). The analyst interprets the dream and assures the man that his nights will be restful if he puts his money in the Banco di Roma.

The other commercials (watch here) are called “The Tunnel Dream” and “The Dream of the Lion in the Cellar.” (You can watch Roberto Di Vito’s short, untranslated film of Fellini and his crew working on the project here.)

The bank commercials were the last films Fellini ever made. He died a year after they aired, at age 73. In Kezich’s view, the deeply personal and imaginative ads amount to Fellini’s last testament, a brief but wondrous return to form. “In Federico’s life,” he writes, “these three commercial spots are a kind of Indian summer, the golden autumn of a patriarch of cinema who, for a moment, holds again the reins of creation.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2012.

Related Content:

Fellini’s Three Bank of Rome Commercials, the Last Thing He Did Behind a Camera (1992)

Watch All of the Commercials That David Lynch Has Directed: A Big 30-Minute Compilation

Ingmar Bergman’s 1950s Soap Commercials Wash Away the Existential Despair

Read More...

The Poetry of Mining Beautiful White Italian Marble Captured in a Short Film

Did anyone ever truly want to be a coal miner? The work was dirty, dangerous, and poorly compensated, the workers exploited and their unions blocked by callow employers.

Coal production is in a state of terminal decline, but the old phrase “it’s not mining coal” endures.

However hard your job may be, it’s not coal mining.

It’s probably not contemporary marble mining either. This may strike you as a pity, after viewing excerpts from Il Capo, filmmaker Yuri Ancarani’s dreamy 15-minute documentary, set in the Bettogli quarry in Tuscany.

As captured above, the shirtless quarry boss’s silent instructions to workers prying enormous slabs of marble from the barren white landscape with industrial excavators are unbelievably lyrical.

Consider yourself lucky if your job is even a fraction as poetic.

Marble mining seems as though it might also be a secret to staying fit—and tan—well into middle age.

I do wonder if vanity caused our middle aged hero to doff his noise-canceling headphones while the camera rolled. These massive slabs do not go down lightly, thus the necessity of non-verbal communication.

The filmmaker states that he was with the delicacy of his subject’s “light, precise and determined” movements. The quarry crew might not find their boss’ physicality reminiscent of a conductor guiding an orchestra through a particularly sensitive movement, but those who caught the film at one of the many galleries, festivals, and museums where it has screened reportedly do.

Clearly, Ancarani has an attraction to work transpiring in unusual landscapes. Il Capo is a part of his Malady of Iron trilogy, which also documents time spent with divers operating from a submarine deep below the ocean’s surface and a surgical robot whose movements inside the human body are controlled via joystick.

via Nowness

Related Content:

How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation

The Making of a Steinway Grand Piano, From Start to Finish

Electric Guitars Made from the Detritus of Detroit

- Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her latest script, Fawnbook, is available in a digital edition from Indie Theater Now. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...40,000 Film Posters in a Wonderfully Eclectic Archive: Italian Tarkovsky Posters, Japanese Orson Welles, Czech Woody Allen & Much More

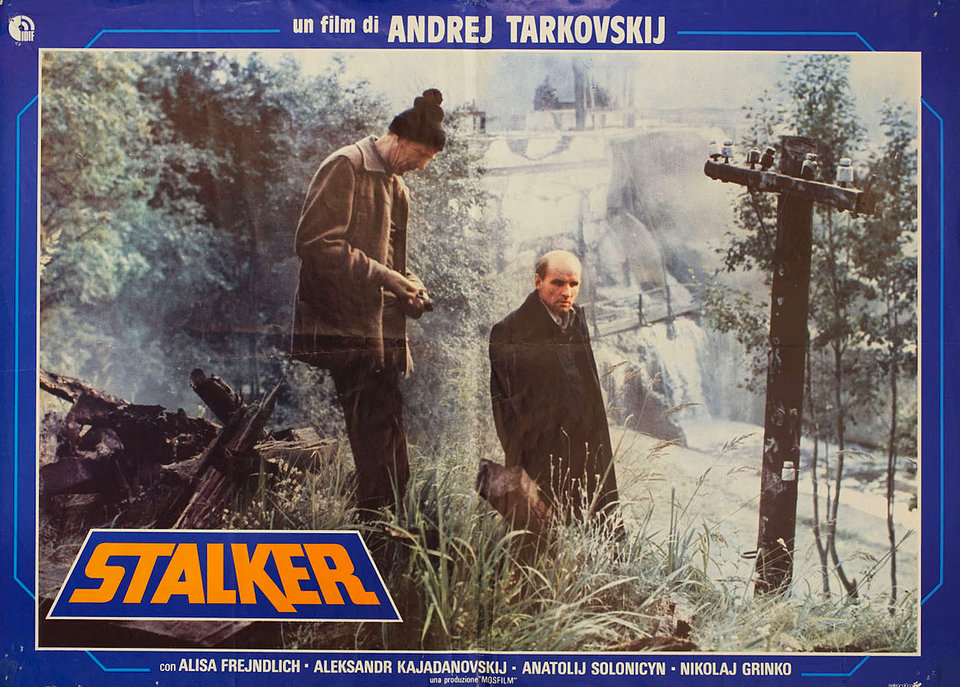

Here we have a poster for a film many of you will have heard of, and some of you will have watched right here on Open Culture: Stalker, widely considered the most masterful of Soviet auteur Andrei Tarkovsky’s career full of masterpieces. Needless to say, the film has inspired no small amount of cinephile enthusiasm in the 37 years since its release, and if it has inspired the same in you, what better way to express it than to hang its poster on your wall? And why not take it to the next level by hanging a Stalker poster from another country, such as the Italian one here?

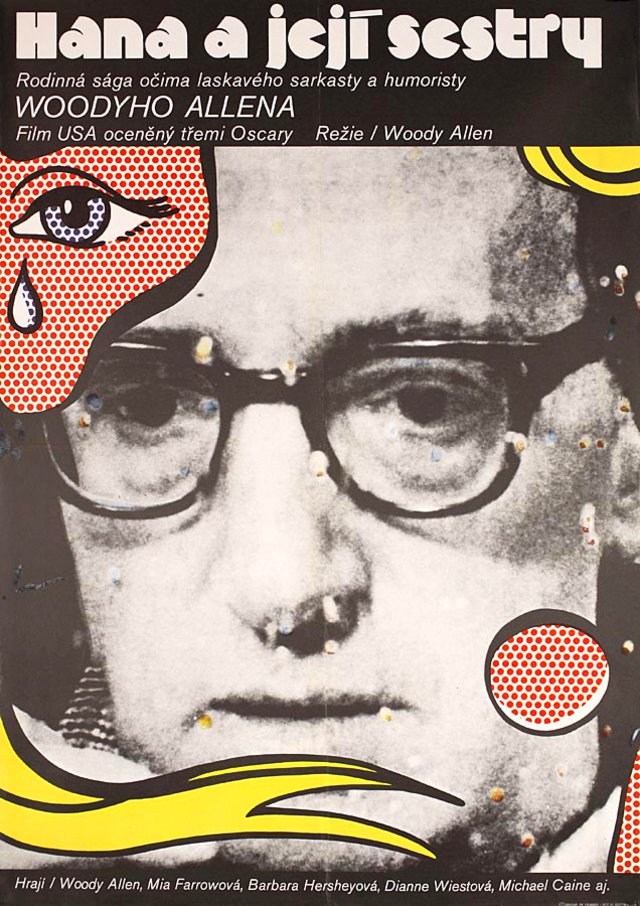

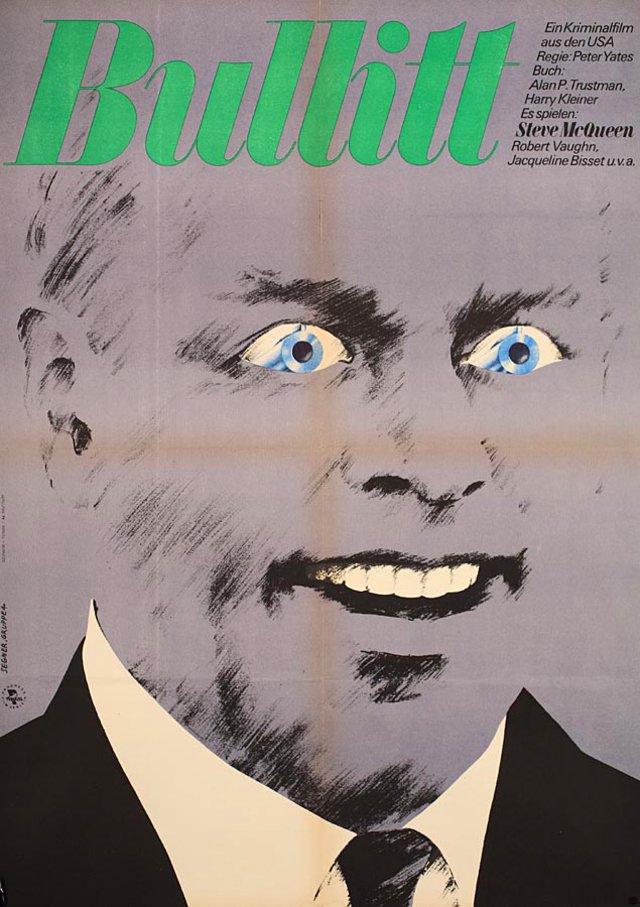

We found it on Posteritati, a New York movie poster gallery whose online store also functions as a digital archive of over 40,000 of these commercial-cinematic works of art, all conveniently sorted into categories: not just Tarkovsky posters, but posters from the former East Germany and Iran, posters from the Czech New Wave, and posters designed by the Japanese artist Tadanori Yokoo (whose works, said no less an observer of the human condition than Yukio Mishima, “reveal all of the unbearable things which we Japanese have inside ourselves”). And that’s just a small sampling of what Posteritati has to offer. If you dig deep enough, you can even find posters from Poland and the Czech Republic with cats in them.

Avid Open Culture readers might find Posteritati’s philosophy section especially worthwhile, containing as it does posters for movies we’ve previously featured and movies about thinkers we like to write about, like Derrida, Examined Life, Wittgenstein, and of course the Slavoj Žižek-starring The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology and Žižek!

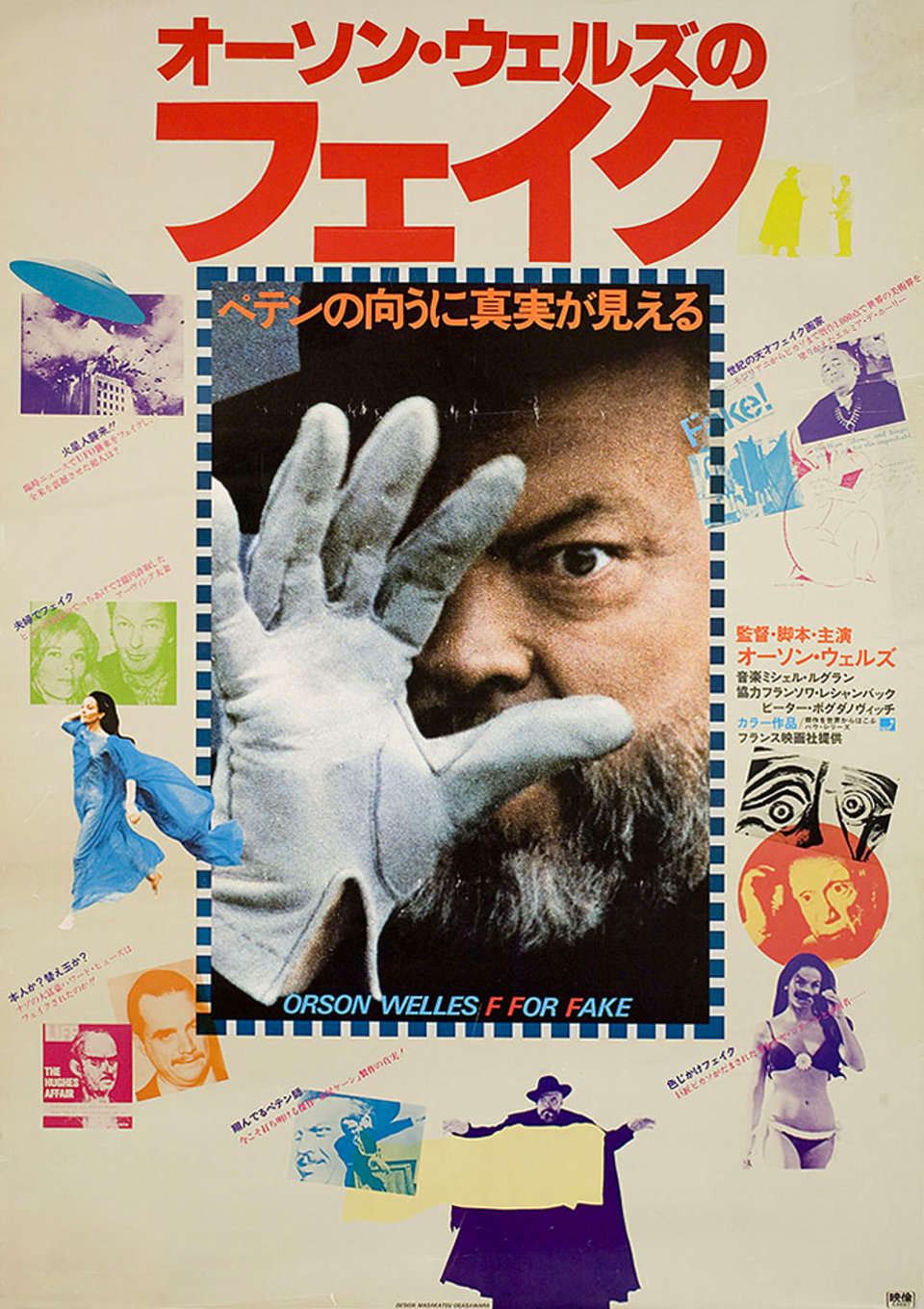

They also sell posters at the site, though even the ones not in stock remain available to view as images: just toggle the “IN STOCK ONLY” switch to the OFF position, and you can then see all of the posters in the collection. No matter what your cinematic, intellectual, or aesthetic interests, you’ll find at least a few posters that pique your interest. The Japanese poster for Orson Welles’ F for Fake just above, for instance, represents a near-perfect intersection of most of my own interests. Just as well Posteritati doesn’t have it in stock — I’d probably pay anything.

Related Content:

50 Film Posters From Poland: From The Empire Strikes Back to Raiders of the Lost Ark

The Strange and Wonderful Movie Posters from Ghana: The Matrix, Alien & More

Japanese Movie Posters of 10 David Lynch Films

A Look Inside Martin Scorsese’s Vintage Movie Poster Collection

100 Greatest Posters of Film Noir

Striking French, Russian & Polish Posters for the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

Watch Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mind-Bending Masterpiece Free Online

F for Fake: Orson Welles’ Short Film & Trailer That Was Never Released in America

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Adapting the Unfilmable Story of Pinnochio — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #143

Your Pretty Much Pop A‑Team Mark Linsenmayer, Lawrence Ware, Sarahlyn Bruck, and Al Baker discuss the original 1883 freaky children’s story by Carlo Collodi and consider the recent rush of film versions, from a new Disney/Robert Zemikis CGI take to Guillermo del Toro’s stop-motion passion project to a heavily costumed Italian version by Matteo Garrone, which is the second to feature Oscar winner Roberto Benigni in a lead role. Benigni’s previous try was a 2002 version that is the most true to the beats of the original story and maybe because of this has a 0% on Rotten Tomatoes. Why do people keep remaking this story, and how has the original moral of “be a good boy and obey” changed over the years?

Read the original story. Some articles going through the film versions include:

- “The twisted history of Pinocchio on screen” by Cindy White

- “Pinocchio: Top 10 Best Movie And TV Adaptations, Ranked by IMDb” by Olivia Hayward

- “Pinocchios, Ranked” by Barry Levitt

- “The Transformations of Pinocchio” by Joan Acocella

- “Pinocchio: The scariest children’s story ever written” by Nicholas Barber

Follow us @law_writes, @sarahlynbruck, @ixisnox, @MarkLinsenmayer.

Hear more Pretty Much Pop. Support the show and hear bonus talking for this and nearly every other episode at patreon.com/prettymuchpop or by choosing a paid subscription through Apple Podcasts. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

Read More...Watch Free Cult Films by Stanley Kubrick, Fritz Lang, Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi & More on the New Kino Cult Streaming Service

For many Open Culture readers, the Halloween season offers an opportunity — not to say an excuse — to re-experience classic horror films: F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu from 1922, for instance, or even George Méliès The Haunted Castle, which launched the whole form in 1896. This year, may we suggest a home screening of the formidable work of vintage cinema that is 1968’s The Astro Zombies? Written, produced, and directed by Ted Mikels — auteur of The Corpse Grinders and Blood Orgy of the She-Devils — it features not just “a mad astro-scientist” played by John Carradine and “two gore-crazed, solar-powered killer robot zombies,” but “a bloody trail of girl-next-door victims; Chinese communist spies; deadly Mexican secret agents led by the insanely voluptuous Tura Satana” and an “intrepid CIA agent” on the case of it all.

You can watch The Astro Zombies for free, and newly remastered in HD to boot, at Kino Cult, the new streaming site from film and video distributor Kino Lorber. Pull up the front page and you’ll be treated to a wealth of titillating viewing options of a variety of eras and subgenres: “Drive-in favorites” like Ape and Beware! The Blob; “golden age exploitation” like Reefer Madness and She Shoulda Said ‘No’!; and even classics like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Stanley Kubrick’s Fear and Desire.

True cult-film enthusiasts, of course, may well go straight to the available selections, thoughtfully grouped together, from “Master of Italian Horror” Mario Bava and prolific Spanish “B‑movie” kingpin Jesús Franco. Those looking to throw a fright night might consider Kino Cult’s offerings filed under “hardboiled horror”: Killbillies, The House with 100 Eyes, Bunny: The Killer Thing.

Few of these pictures skimp on the grotesque; fewer still skimp on the humor, a necessary ingredient in even the most harrowing horror movies. Far from a pile of cynical hackwork, Kino Cult’s library has clearly been curated with an eye toward films that, although for the most part produced inexpensively and with unrelenting intent to provoke visceral reactions in their audiences, are hardly without interest to serious cinephiles. The site even includes an “artsploitation” section containing such taboo-breaching works as Curtis Burz’s Summer House. Among its general recent additions you’ll also find Dogtooth by Yorgos Lanthimos, perhaps the most daring high-profile provocateur currently at work in the medium. Since Kino Cult has made all these films and more available to stream at no charge, none of us, no matter our particular cinematic sensibilities, has an excuse to pass this Halloween un-entertained — and more to the point, undisturbed. Enter the collection here.

Related Content:

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & MoreThe First Horror Film, George Méliès’ The Haunted Castle (1896)

Watch Nosferatu, the Seminal Vampire Film, Free Online (1922)

Martin Scorsese Creates a List of the 11 Scariest Horror Films

Stephen King’s 22 Favorite Movies: Full of Horror & Suspense

Time Out London Presents The 100 Best Horror Films: Start by Watching Four Horror Classics Free Online

What Scares Us, and How Does this Manifest in Film? A Halloween Pretty Much Pop Culture Podcast (#66)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch the Hugely-Ambitious Soviet Film Adaptation of War and Peace Free Online (1966–67)

On the question of whether novels can successfully be turned into films, the cinephile jury remains out. In the best cases a filmmaker takes a literary work and reinvents it almost entirely in accordance with his own vision, which usually requires a book of modest or unrealized ambitions. This method wouldn’t do, in other words, for War and Peace. Yet Tolstoy’s epic novel, whose sheer historical, dramatic, and philosophical scope has made it one of the most acclaimed works in the history of literature, has been adapted over and over again: for radio, for the stage, as a 22-minute Yes song, and at least four times for the screen.

The first War and Peace film, directed by and starring the pioneering Russian filmmaker Vladimir Gardin, appeared in 1915. Japanese activist filmmaker Fumio Kamei came out with his own version just over three decades later. Only in the nineteen-fifties, with large-scale literary adaptation still in vogue, did the mighty hand of Hollywood take up the book. The project went back to 1941, when producer Alexander Korda tried to put it together under the direction of Orson Welles, fresh off Citizen Kane.

For better or worse, Welles’ version would surely have proven more memorable than the one that opened in 1956: King Vidor’s War and Peace expediently hacked out great swathes of Tolstoy’s novel, resulting in a lush but essentially unfaithful adaptation. This was still early in the Cold War, a struggle conducted through the amassing of soft power as well as hard. “It is a matter of honor for the Soviet cinema industry,” declared an open letter published in dthe Soviet press, “to produce a picture which will surpass the American-Italian one in its artistic merit and authenticity.”

The gears of the Soviet Ministry of Culture were already turning to get a superior War and Peace film into production — superior in scale, but far superior in fealty to Tolstoy’s words. This put a formidable challenge in front of Sergei Bondarchuk, who was selected as its director and who, like Gardin before him, eventually cast himself in the starring role of Count Pyotr “Pierre” Kirillovich Bezukhov. As a production of Mosfilm, national studio of the Soviet Union, War and Peace could marshal an unheard-of volume of resources to put early nineteenth-century Russia onscreen. Its furniture, fixtures, and other objects came from more than forty museums, and its thousands of uniforms and pieces of military hardware from the Napoleonic Wars were recreated by hand.

The most expensive production ever made in the Soviet Union, War and Peace was also rumored to be the most expensive production in the history of world cinema to date. With a total runtime exceeding seven hours, it was released in four parts throughout 1966 an 1967. Now, thanks to Mosfilm’s Youtube channel, you can watch them all free on Youtube. 55 years later, its production values still radiate from each and every frame, something you can appreciate even if you know nothing more of War and Peace than that — as a non-Russian filmmaker of comparatively modest production sensibilities once said — it’s about Russia.

Related content:

Why Should We Read Tolstoy’s War and Peace (and Finish It)? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case

The Art of Leo Tolstoy: See His Drawings in the War & Peace Manuscript & Other Literary Texts

Free Online: Watch Stalker, Mirror, and Other Masterworks by Soviet Auteur Andrei Tarkovsky

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Italian Advice on How to Live the Good Life: Cigarettes, Tomatoes, and Other Picturesque Small Pleasures

“I guess everybody’s got a dream and we’re all hoping to see it come true,” muses Giovanni Mimmo Mancusou, a philosophical native of Calabria, the lovely, sun-drenched region forming the toe of Italy’s boot, above. “A dream coming true is better than just a dream.”

Filmmakers Jan Vrhovnik and Ana Kerin were scouting for subjects to embody “the very essence of nostalgia” when they chanced upon Mancusou in a corner shop.

A lucky encounter! Not every non-actor — or for that matter, actor — is as comfortable on film as the laidback Mancusou.

(Vrhovnik has said that he invariably serves as his own camera operator when working with non-actors, because of the potential for intimacy and intuitive approach that such proximity affords.)

Mancusou, an advocate for simple pleasures, also appears to be quite fit, which makes us wonder why the film’s description on NOWNESS doubles down on adjectives like “aging”, “older” and most confusingly, “wisened.”

Merriam-Webster defines “wizened” with a z as “dry, shrunken, and wrinkled often as a result of aging or of failing vitality” … and “wisened” not at all.

Perhaps NOWNESS meant wise?

We find ourselves craving a lot more context.

Mancusou has clearly cultivated an ability to savor the hell out of a ripe tomato, his picturesque surroundings, and his ciggies.

“Serenity, joy, ecstasy” is embroidered across the back of his ball cap.

His manner of expressing himself does lend itself to a “poetic thought piece”, as the filmmakers note, but might that not be a symptom of struggling to communicate abstract thoughts in a foreign tongue?

We really would love to know more about this charming guy… his family situation, what he does to make ends meet, his actual age.

Home movies accompany his nostalgic reverie, but did he provide this footage to his new friends?

Did they hunt it down on ebay? It definitely fits the vibe, but is the man with the eyebrows Mancusou at an earlier age?

Our star pulls up to a small petrol station, declares, “All right, here we go,” and the next frame shows him wearing a headlamp and magnifier as he peers into the workings of a pocket watch:

Time out of mechanical. It’s magic.

Is this a hobby? A profession? Does he repair watches in a darkened gas station?

The filmmakers aren’t saying and the blurred background offers no clues either. Curse you, depth of field!

We’re not even given his home coordinates.

The film, part of the NOWNESS series Portrait of a Place, is titled Paradiso, and there is indeed a village so named adjacent to the town of Belvedere Marittimo, but according to census data we found on line, it has only 14 residents, 7 male.

If that’s where Mancusou lives, he’s either 45–49, 65–69, 70–74, or one of two fellows over age 74…and now we’re really curious about his neighbors, too.

No shade to Signor Mancuso, but we’re glad to know we’re not the only viewers left unsatisfied by this portrait’s lack of depth.

One commenter who chafed at the lack of specificity (“this video is a random portrait of basically anyone in the world that is happy with the little he has”) suggested the omissions contribute to an Italian stereotype familiar from pasta sauce commercials:

People in Italy actually work and have ambitions you know? And often are very well-educated and hard-working. The perspective of Italy that you have comes from the American media and Italian post-war neorealism. Indeed, Oscar-winning Italian people complained about the fact that what the media wants is seeing Italians wearing tank tops doing nothing if not mafia or smelling the roses.

Watch more entries in the NOWNESS Portrait of a Place series here.

Related Content

What Are the Keys to Happiness? Lessons from a 75-Year-Long Harvard Study

Positive Psychology: A Free Online Course from Harvard University

The Science of Well-Being: Take a Free Online Version of Yale University’s Most Popular Course

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...

The Forgotten Women of Surrealism: A Magical, Short Animated Film

“The problem of woman is the most marvelous and disturbing problem in all the world,” — Andre Breton, 1929 Surrealist Manifesto.

“I warn you, I refuse to be an object.” — Leonora Carrington

Fashion model, writer, and photographer Lee Miller had many lives. Discovered by Condé Nast in New York (when he pulled her out of the path of traffic), she became a famous face of Vogue in the 1920s, then launched her own photographic career, for which she has been justly celebrated: both for her work in the fashion world and on the battlefields (and Hitler’s tub!) in World War II. One of Miller’s achievements often gets left out in mentions of her life, the Surrealist work she created as an artist in the 1930s.

Hailed as a “legendary beauty,” writes the National Galleries of Scotland, Miller studied acting, dance, and experimental theater. “She learned photography first through being a subject for the most important fashion photographers of her day, including Nickolas Muray, Arnold Genthe and Edward Steichen.” Her apprenticeship and affair with Man Ray is, of course, well-known. But rather than calling Miller an active participant in his art and her own (she co-created the “solarization” process he used, for example) she’s mostly referred to only as his muse, lover, and favorite subject.

“Surrealism had a very high proportion of women members who were at the heart of the movement, but who often get cast as ‘muse of’ or ‘wife of,’ ” says Susanna Greeves, curator of an all-women Surrealist exhibit in South London. The marginalization of women Surrealists is not a historical oversight, many critics and scholars contend, but a central feature of the movement itself. When British Surrealist Eileen Agar said in a 1990 interview, “In those days, men thought of women simply as muses,” she was too polite by half.

Despite their radical politics, male Surrealists perfected turning women into disfigured objects. “While Dalí used the female figure in optical puzzles, Magritte painted pornified faces with breasts for eyes, and Ernst simply decapitated them,” Izabella Scott writes at Artsy. Surrealist artist René Crevel wrote in 1934, “the Noble Mannequin is so perfect. She does not always bother to take her head, arms and legs with her.” Edgar Allan Poe’s love for “beautiful dead girls” escalated into dismemberment.

Dalí employed no lyrical obfuscation in his thoughts on the place of women in the movement. He called his contemporary, Argentine/Italian artist Leonor Fini (who never considered herself a Surrealist), “better than most, perhaps.” Then he felt compelled to add, “but talent is in the balls.”

When writing her dissertation on Surrealism in the 1970s at New York University, Gloria Feman Orenstein found that all of the women had been totally left out of the record. So she found them — tracking down and becoming “a close friend to many influential female surrealists,” notes Aeon, “including Leonora Carrington and Meret Elisabeth Oppeneim” (another Man Ray model and the only Surrealist of any gender to have actual training and experience in psychoanalysis).

Through her research, Orenstein “became the academic voice of feminist surrealism,” recovering the work of artists who had always been part of the movement, but who had been shouldered aside by male contemporaries, lovers, and husbands who did not see them on equal terms. In the short film above, Gloria’s Call, L.A.-based artist Cheri Gaulke “manifests Orenstein’s journey into the surreal with collage-like animations.” It was a quest that took her around the world, from Paris to Samiland, and it began in Mexico City, where she met the great Leonora Carrington.

See how Orenstein not only rediscovered the women of Surrealism, but helped recover the essential roots of Surrealism in Latin America, also erased by the art historical scholarship of her time. And learn more about the artists she befriended and brought to light at Artspace and in Penelope Rosemont’s 1998 book, Surrealist Women: An International Anthology.

Related Content:

An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Postwar Italian Cinema Created La Dolce Vita and Then the Paparazzi

Those who love the work of Federico Fellini must envy anyone who sees La Dolce Vita for the first time. But today such a viewer, however overwhelmed by the lavish cinematic feast laid before his eyes, will wonder if giving the intrusive tabloid photographer friend of Marcello Mastroianni’s protagonist the name “Paparazzo” isn’t a bit on the nose. Unlike La Dolce Vita’s first audiences in 1960, we’ve been hearing about real-life paparazzi throughout most all of our lives, and thus may not realize that the word itself originally derives from Fellini’s masterpiece. Each time we refer to the paparazzi, we pay tribute to Paparazzo.

In the video essay above, Evan Puschak (better known as the Nerdwriter) traces the origins of paparazzi: not just the word, but the often bothersome professionals denoted by the word. The story begins with the dictator Benito Mussolini, an “avid movie fan and fanboy of film stars” who wrote “more than 100 fawning letters to American actress Anita Page, including several marriage proposals.” Knowing full well “the emotional power of cinema as a tool for propaganda and building cultural prestige,” Mussolini commissioned the construction of Rome’s Cinecittà, the largest film-studio complex in Europe when it opened in 1937 — six years before his fall from power.

During the Second World War, Cinecittà became a vast refugee camp. When peacetime returned, with “the studio space being used and Mussolini’s thumb removed, a new wave of filmmakers took to the streets of Rome to make movies about real life in postwar Italy.” Thus began the age of Italian Neorealism, which brought forth such now-classic pictures as Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City and Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. In the nineteen-fifties, major American productions started coming to Rome: Quo Vadis, Roman Holiday, Ben-Hur, Cleopatra. (It was this era, surely, that inspired an eleven-year-old named Martin Scorsese to storyboard a Roman epic of his own.) All of this created an era known as “Hollywood on the Tiber.”

For a few years, says Puschak, “the Via Veneto was the coolest place in the world.” Yet “while the glitterati cavorted in chic bars and clubs, thousands of others struggled to find their place in the postwar economy.” Some turned to tourist photography, and “soon found they could make even more money snapping photos of celebrities.” It was the most notorious of these, the “Volpe di via Veneto” Tazio Secchiaroli, to whom Fellini reached out asking for stories he could include in the film that would become La Dolce Vita. The newly christened paparazzi were soon seen as the only ones who could bring “the gods of our culture down to the messy earth.” These six decades later, of course, celebrities do it to themselves, social media having turned each of us — famous or otherwise — into our own Paparazzo.

Related content:

Federico Fellini Introduces Himself to America in Experimental 1969 Documentary

Cinecittà Luce and Google to Bring Italy’s Largest Film Archive to YouTube

Mussolini Sends to America a Happy Message, Full of Friendly Feelings, in English (1927)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Francis Ford Coppola Breaks Down His Most Iconic Films: The Godfather, Apocalypse Now & More

Fifty years after its theatrical release, The Godfather remains a subject of lively cinephile conversation. What, as any of us might ask after a fresh semi-centennial viewing of Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia masterpiece, is this movie about? We need only ask Coppola himself, who has our answer in one word: succession. In the recent GQ interview above, he also explains the themes of other major works with similar succinctness: Apocalypse Now is about morality; The Conversation is about privacy. Such clean and simple encapsulations belie the nature of the film production process, and especially that of Coppola’s nineteen-seventies pictures, with their large scale, seriousness of purpose, and proneness to severe difficulty.

“What we consider real art is a movie that does not have a safety net,” Coppola says, and that applies without a doubt to movies like The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. Much as Orson Welles once said of his own experience making Citizen Kane, the young Coppola went into The Godfather ignorant of more or less everything involved in its content but life in an Italian-American family. But he had, in theater school, learned the techniques of “outwitting the faculty,” and dealing with the higher-ups at Hollywood studios turned out to require that same skill set. He thus found a way to include every element ruled insistently out by the executives, from New York locations and a period setting to performers like the then-unknown Al Pacino and then-washed-up Marlon Brando.

Brando didn’t take part in The Godfather Part II, but he did show up at the end of Apocalypse Now for a vividly memorable turn as the power-mad Colonel Kurtz. As Coppola remembers it, “when Brando arrived, he looked at me — he’s so smart — and he said, ‘You painted yourself in a corner, didn’t you?” The actor meant that the surreal qualities of the film had reached such an intensity that no conventional form of resolution could possibly suffice. This was the result of the fact that, as Coppola puts it, “one of the things that make a movie is the movie: it contributes to making itself.” In other words, as Coppola and his collaborators shot each scene (a process that famously resulted in over one million feet of footage), the very film taking shape before them suggested its own direction — in the case of Apocalypse Now, toward the ever darker and stranger.

Always candid about his professional struggles, Coppola has also been generous with technical and artistic explanations of just how his pictures have come together. Godfather fans will delight in his director’s-commentary tracks on the first and second parts of that trilogy; as for The Godfather Part III, Coppola released a new edit (in the manner of Apocalypse Now’s Redux and Final Cut) called The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone in 2020. He discusses that project in the GQ interview, and also his work-in-progress Megalopolis. Having described The Godfather as essentially a Shakespearean tale, he’s now reaching further back in time: “Wouldn’t it be interesting if you made a Roman epic but didn’t set it in ancient Rome — set it in modern New York?” He also lets us in on Megalopolis’ surprising key word: not megalomania, nor ambition, nor power, but sincerity.

Related content:

A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Casting of The Godfather with Coppola, Pacino, De Niro & Caan

Francis Ford Coppola’s Handwritten Casting Notes for The Godfather

Orson Welles Explains Why Ignorance Was His Major “Gift” to Citizen Kane

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...