“All my jokes are Indianapolis,” Kurt Vonnegut once said. “All my attitudes are Indianapolis. My adenoids are Indianapolis. If I ever severed myself from Indianapolis, I would be out of business. What people like about me is Indianapolis.” He delivered those words to a high-school audience in his hometown of Indianapolis in 1986, and a decade later he made his feelings even clearer in a commencement speech at Butler University: “If I had to do it all over, I would choose to be born again in a hospital in Indianapolis. I would choose to spend my childhood again at 4365 North Illinois Street, about 10 blocks from here, and to again be a product of that city’s public schools.” Now, at 543 Indiana Avenue, we can experience the legacy of the man who wrote Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat’s Cradle, and Breakfast of Champions at the newly permanent Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library.

The museum’s founder and CEO Julia Whitehead “conceived the idea for a Vonnegut museum in November of 2008, a year and a half after the author’s death, writes Atlas Obscura’s Susan Salaz. “The physical museum opened in a donated storefront in 2011, displaying items donated by friends or on loan from the Vonnegut family” — his Pall Malls, his drawings, a replica of his typewriter, his Purple Heart.

But the collection “has been homeless since January 2019.” A fundraising campaign this past spring raised $1.5 million in donations, putting the museum in a position to purchase the Indiana Avenue building, one capacious enough for visitors to, according to the museum’s about page, “view photos from family, friends, and fans that reveal Vonnegut as he lived; “ponder rejection letters Vonnegut received from editors”; and “rest a spell and listen to what friends and colleagues have to say about Vonnegut and his work.”

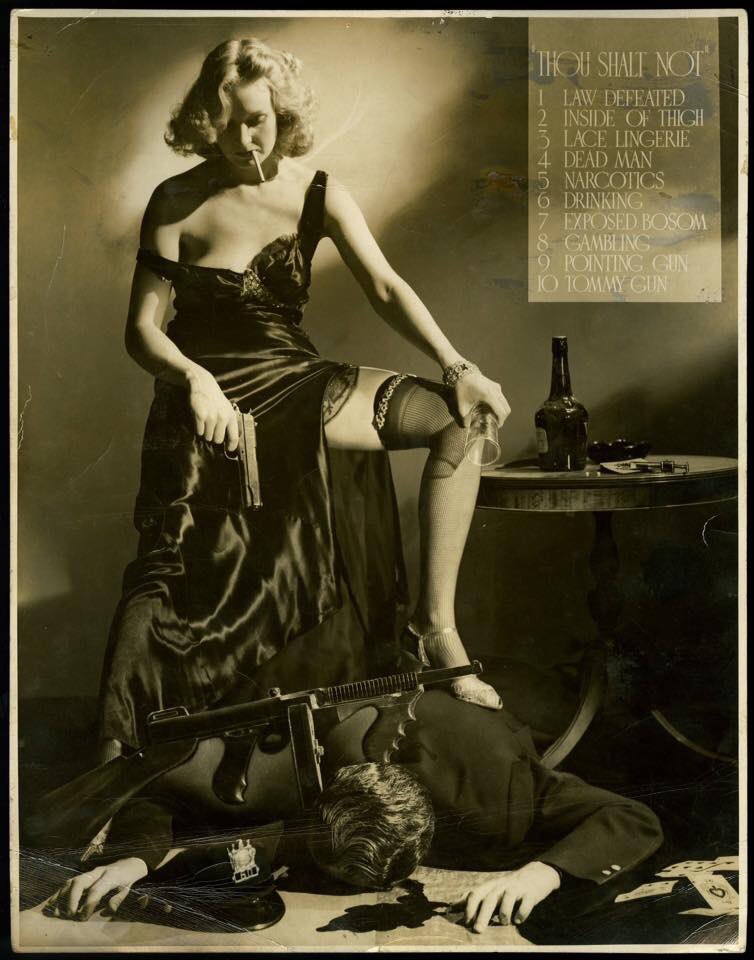

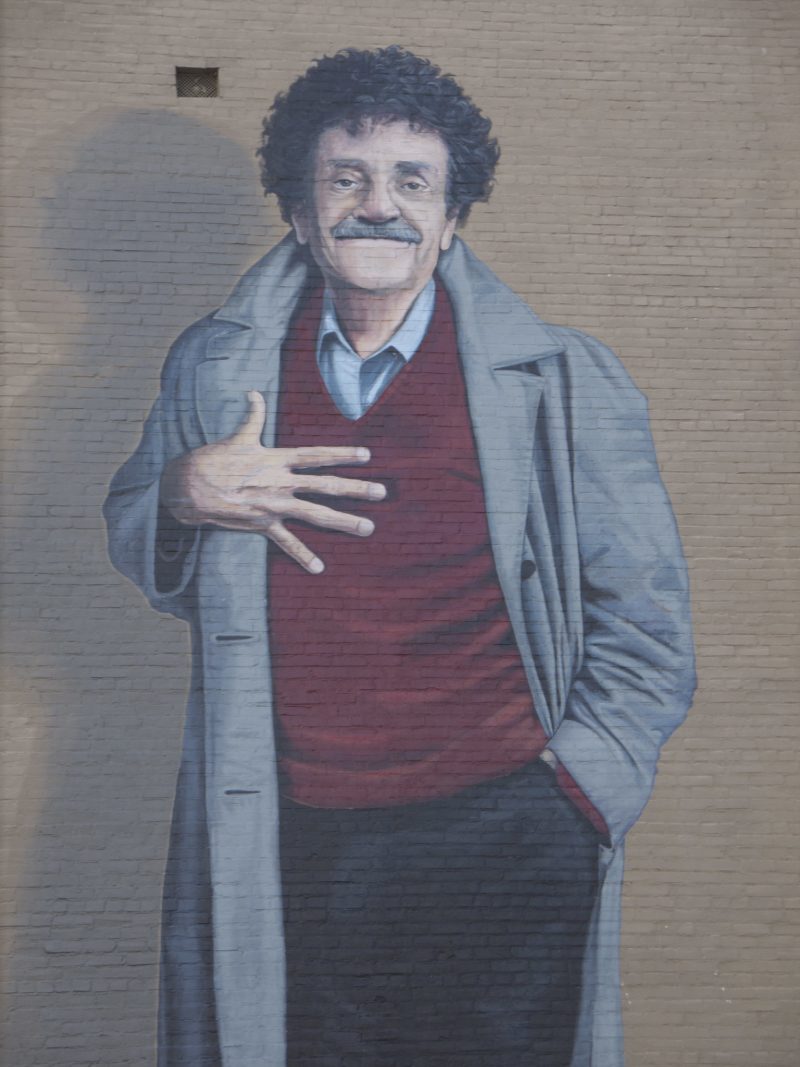

The newly re-opened Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library will also pay tribute to the jazz-loving, censorship-loathing veteran of the Second World War with an outdoor tunnel playing the music of Wes Montgomery and other Indianapolis jazz greats, a “freedom of expression exhibition” that Salaz describes as featuring “the 100 books most frequently banned in libraries and schools across the nation,” and veteran-oriented book clubs, writing workshops, and art exhibitions. In the museum’s period of absence, Vonnegut pilgrims in Indianapolis had no place to go (apart from the town landmarks designed by the writer’s architect father and grandfather), but the 38-foot-tall mural on Massachusetts Avenue by artist Pamela Bliss. Having known nothing of Vonnegut’s work before, she fell in love with it after first visiting the museum herself, she’ll soon use its Indiana Avenue building as a canvas on which to triple the city’s number of Vonnegut murals.

You can see more of the new Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, which opened its doors for a sneak preview this past Banned Books Week, in the video at the top of the post, as well as in this four-part local news report. Though Vonnegut expressed appreciation for Indianapolis all throughout his life, he also left the place forever when he headed east to Cornell. He also satirically repurposed it as Midland City, the surreally flat and prosaic Midwestern setting of Breakfast of Champions whose citizens only speak seriously of “money or structures or travel or machinery,” their imaginations “flywheels on the ramshackle machinery of awful truth.” I happen to be planning a great American road trip that will take me through Indianapolis, and what with the presence of an institution like the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library — as well as all the cultural spots revealed by the Indianapolis-based The Art Assignment — it has become one of the cities I’m most excited to visit. Vonnegut, of all Indianapolitans, would surely appreciate the irony.

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Kurt Vonnegut? An Animated Video Makes the Case

Kurt Vonnegut Creates a Report Card for His Novels, Ranking Them From A+ to D

Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization

Behold Kurt Vonnegut’s Drawings: Writing is Hard. Art is Pure Pleasure

22-Year-Old P.O.W. Kurt Vonnegut Writes Home from World War II: “I’ll Be Damned If It Was Worth It”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.