Cameras are small, and getting smaller all the time. This development has helped us all document our lives, sharing the sights we see with an ease difficult to imagine even twenty years ago. 120 years ago, photography faced an entirely different set of challenges, but then as now, much of the motivation to meet them came from commercial interests. Take the case of Chicago photographer George R. Lawrence and his client the Chicago & Alton Railway, who wanted to promote their brand-new Chicago-to-St. Louis express service, the Alton Limited. This product of the golden age of American train travel demanded some respectable photography, a technology then still in its thrilling, possibility-filled emergence.

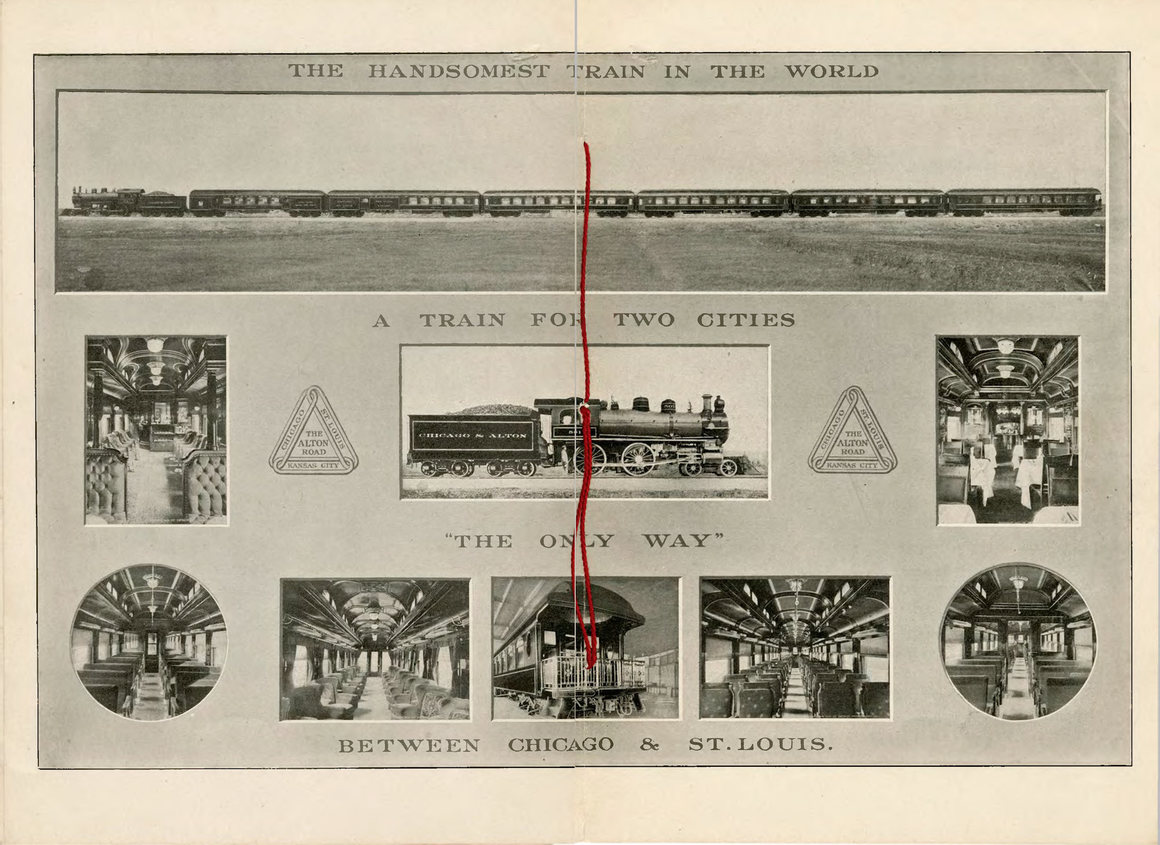

A truly elegant piece of work, the Alton Limited would, during its 72-year lifespan, boast such features as a post office, a library, a Japanese tea-room, and a striking maroon-and-gold color scheme that earned it the nickname “the Red Train.”

Even from a distance, the Alton Limited looked upon its introduction in 1899 like nothing else on the railroads, with its six identical Pullman cars all designed in perfect symmetry — the very aspect that so challenged Lawrence to capture it in a photograph. Simply put, the whole train wouldn’t fit in one picture. While he could have shot each car separately and then stitched them together into one big print, he rejected that technique for its inability to “preserve the absolute truthfulness of perspective.”

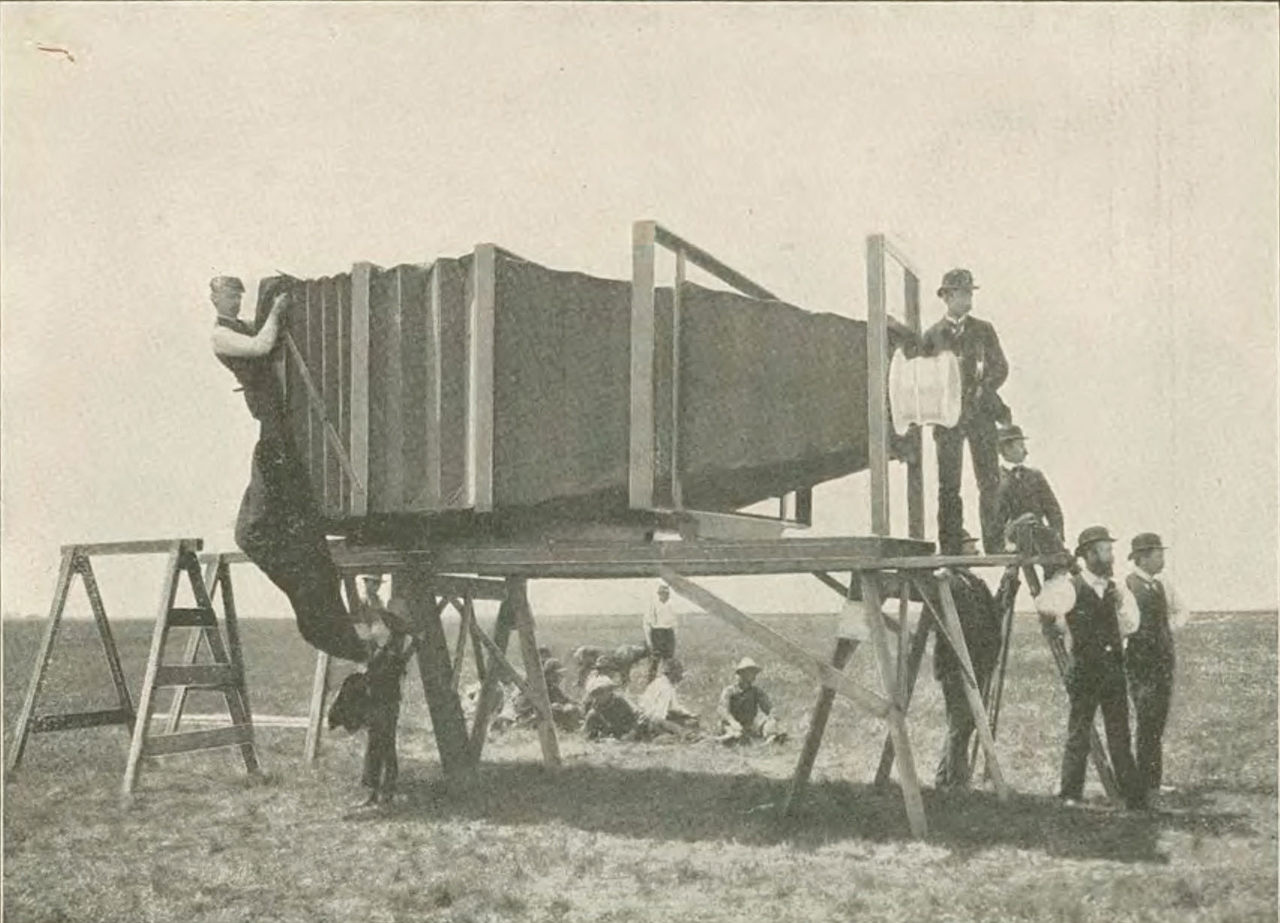

Only a much bigger camera, Lawrence knew, could capture the whole train. And so, in the words of Atlas Obscura’s Anika Burgess, he “quickly went to work designing a camera that could hold a glass plate measuring 8 feet by 4 1/2 feet. It was constructed by the camera manufacturer J.A. Anderson from natural cherry wood, with bespoke Carl Zeiss lenses (also the largest ever made). The camera alone weighed 900 pounds. With the plate holder, it reached 1,400 pounds. According to an August 1901 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the bellows was big enough to hold six men, and the whole camera took a total of 15 workers to operate.” Transporting the camera to Brighton Park, “an ideal vantage point from which to shoot the waiting train,” required another team of men, and developing the eight-foot long photo took ten gallons of chemicals.

The advertisements in which Lawrence’s photograph appeared practically glowed with pride in the Alton Limited, billing it as “a train for two cities,” as “the only way between Chicago and St. Louis,” as “the handsomest train in the world.” The whole-train picture beggared belief: though it went on to win Lawrence the Grand Prize for World Photographic Excellence at the 1900 Paris Exposition, Burgess notes, it looked so impossible that both the photographer and Chicago & Alton “had to submit affidavits to verify that the photograph had been made on one plate.” We in the 21st century, of course, have no reason to doubt its authenticity, or even to marvel at its ingenuity until we know the story of the immense custom camera with which Lawrence shot it. Today, what awes us are all those smaller shots of the Alton Limited’s interior, exuding a luxuriousness that has long vanished from America’s railroads. If we were to find ourselves on such a train today, we’d surely start Instagramming it right away.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Behold a Beautiful Archive of 10,000 Vintage Cameras at Collection Appareils

19-Year-Old Student Uses Early Spy Camera to Take Candid Street Photos (Circa 1895)

See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838)

The History of Photography in Five Animated Minutes: From Camera Obscura to Camera Phone

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.