All of David Lynch’s movies, television shows, music videos, and commercials — and also his paintings, photographs, and comic strips — express a consistent, and consistently Lynchian, vision. But that vision depends on more than just the visual: the sonic has also played a vital part in its development at least since the nightmarishly intricate sound design of Lynch’s 1977 debut feature Eraserhead. And just imagine how much impact later Lynch projects like Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, The Straight Story, and Mulholland Drive would have lost without the rich and often haunting scores of Angelo Badalamenti, a composer with whom Lynch has worked at seemingly every opportunity.

Lynch made his own official debut as a recording artist seven years ago with Crazy Clown Time, and this November he and Badalamenti will release their first collaborative album Thought Gang. According to its Bandcamp page, this “esoteric jazz side project of David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti evolved from the seeds of Twin Peaks’ trademark slow cool jazz and blossomed into more experimental pastures: horizonless vistas of acid-soaked freejazz, laced with spoken word narratives and sprawling noisescapes.” If that sounds good to you, you can get a first taste of the album from the track “Woodcutters From Fiery Ships” above.

The Thought Gang sessions happened 25 years ago, between the end of Twin Peaks’ second season and the production of the Twin Peaks movie Fire Walk with Me. Out of those sessions came a quantity of music that Lynch describes as “sort of like jet-fueled jazz in a weird way… but it’s all based on stories.” Two of those tracks, “A Real Indication” and “The Black Dog Runs at Night,” appeared on the soundtrack of the movie, and two others, “Frank 2000” and “Summer Night Noise,” (as well as the instrumental mix of another, “Logic and Common Sense”) feature in Twin Peaks: The Return, which aired on Showtime last year. More connections to Lynch’s other work surface in “Woodcutters From Fiery Ships,” beginning with its title, which adorned a Lynch-themed, seemingly never-developed CD-ROM game twenty years ago.

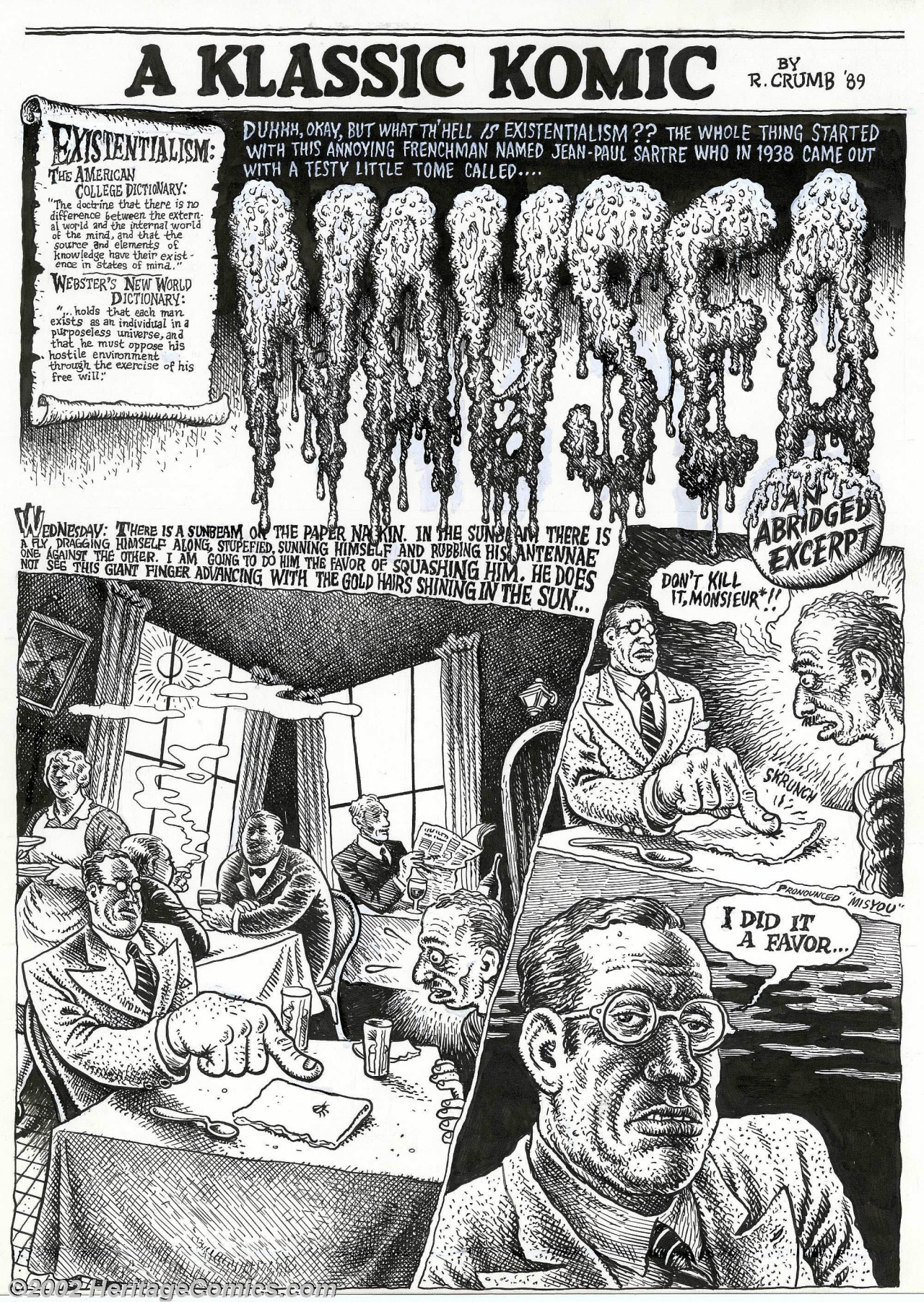

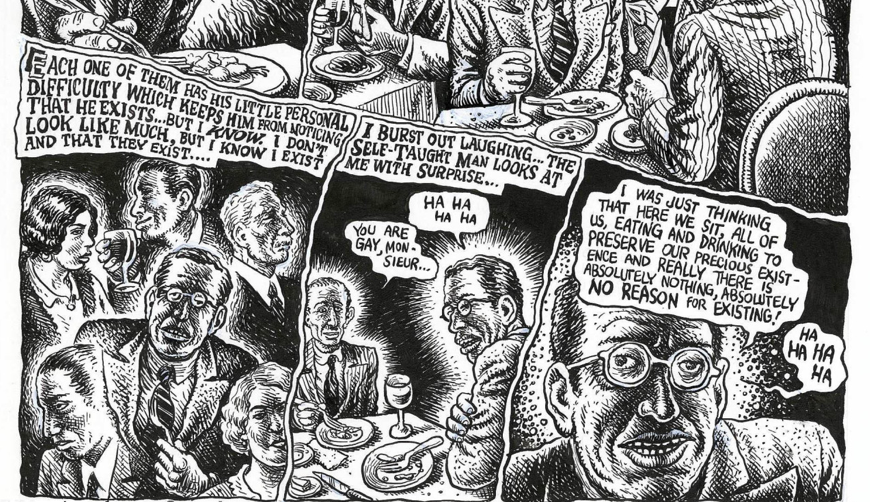

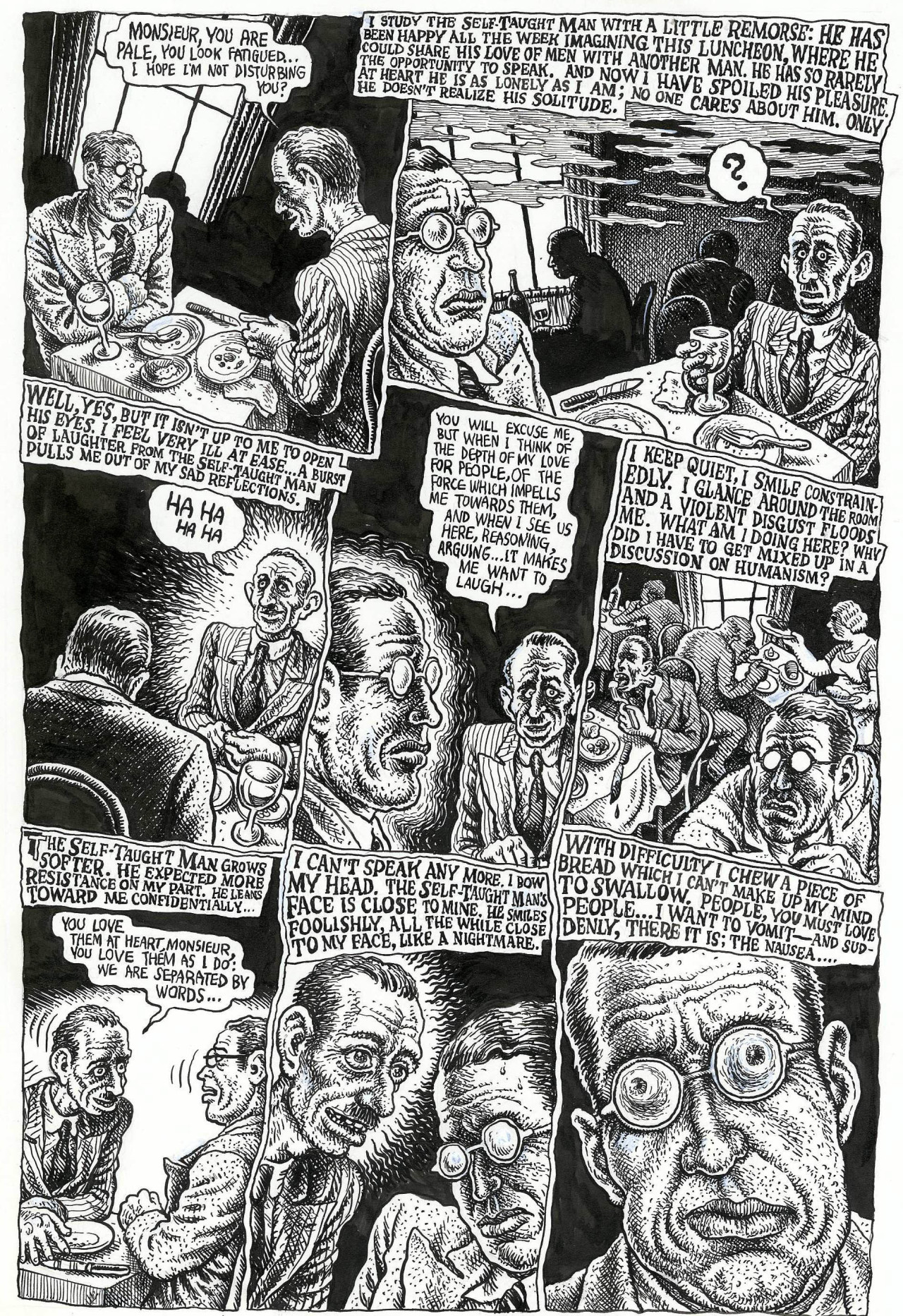

Much of the Lynchian imagery that fills the song — talk-sung by Badalamenti himself, who, says the Bandcamp page, summoned “such a violent laughter-fueled excitement from Lynch that he literally induced a hernia” — may also sound familiar. A character called Pete “saw the girl next door take off her clothes last night and walk through her house nude.” At a diner, “he heard a man say that the doctors had cut him down his neck and into his chest.” A “grey man with big ears lit a big cigar” and “smoke drifted over Pete’s apple pie.” Badalamenti at one point declares that “things aren’t making sense. For instance, why is that boy bleeding from the mouth?” True fans will recognize that line as the title of one of Lynch’s paintings. And so the grand Lynchian project continues, somehow getting both weirder and more coherent all the time.

Related Content:

Angelo Badalamenti Reveals How He and David Lynch Composed the Twin Peaks‘ “Love Theme”

Hear the Music of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks Played by the Danish National Symphony Orchestra

David Lynch’s Music Videos: Nine Inch Nails, Moby, Chris Isaak & More

David Lynch’s New ‘Crazy Clown Time’ Video: Intense Psychotic Backyard Craziness (NSFW)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.