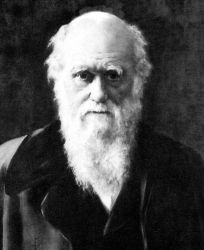

At least in America, Charles Darwin has become the favorite whipping boy for many fundamentalists on the right. In one neat package, you get in Darwin all things deplorable. A godless “secular humanist” who denied the sanctity of humanity, God’s providence, and the integrity of the Bible. What more could you love to hate?

At least in America, Charles Darwin has become the favorite whipping boy for many fundamentalists on the right. In one neat package, you get in Darwin all things deplorable. A godless “secular humanist” who denied the sanctity of humanity, God’s providence, and the integrity of the Bible. What more could you love to hate?

Somewhere lost in today’s culture wars is the real Charles Darwin. Aired first in October, this program, produced by American Public Media’s Speaking of Faith (MP3 — iTunes — Feed — Web Site), revisits Darwin’s life & thought with James Moore, a Cambridge University scholar who has written Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist. And here’s the picture that we get. Like many important scientists who came before him — Galileo, Copernicus and Newton — Darwin believed that science could help explain the laws of nature created by God. Further, he saw his Origin of Species as describing the forms of life that owed their existence to God’s law — a law that expressed itself in natural selection. Readers will find that Darwin’s text is littered with references to creation. And Darwin, himself, was noted for saying that when he wrote the book, his faith in God was as strong as that of a bishop, although his faith did wane latter in life. Simply put, Darwin was hardly the enemy of religion that many consider him today.

Again, you can access this program with the following links: (MP3 — iTunes — Feed — Web Site). Additionally, you can access a free e‑text of On the Origin of Species here, along with a free audiobook version here.

You may also want to check out a related program by Speaking of Faith: Einstein and the Mind of God