Question for the drinkers out there:

Does strong beer taken in moderate quantities at mealtimes make you cheerful?

Yeah, me too!

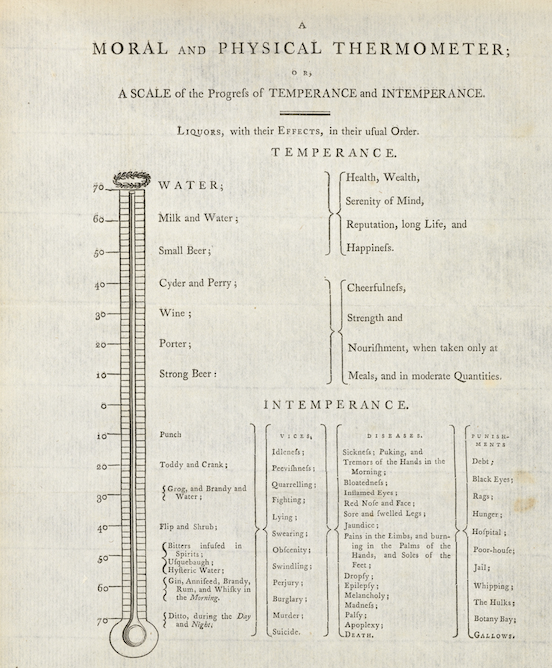

That gives us a temperature of 10 according to 18th-century physician John Coakley Lettsom’s “moral and physical thermometer,” one of his Hints Designed to Promote Beneficence, Temperance, and Medical Science (1797).

It’s nothing to be ashamed of—anything above zero constitutes a passing score. The founder of the Medical Society of London, Lettsom was a proponent of true temperance, not total abstinence. According to his rubric, a “small beer” has all the virtues of milk and water.

Dip below a zero, though, and you’re in for a bumpy night.

Punch is apparently the gateway to such demon influences as flip, shrub, whiskey and rum. Gosh. You may as well just skip the punch and go straight for the hard stuff, if, as in Lettsom’s view, they all end in the same vices and diseases.

Puking and Tremors of the Hands in the Morning?

Yes, on occasion.

Peevishness, Idleness, and Obscenity?

Yep, that too.

Murder, Madness, and Death?

Mercifully, no. At least not yet.

While not entirely free of stigma, alcoholism is now something many view through the lens of AA, a problem best remedied through a system of personal accountability shored up by a network of nonjudgmental, sympathetic support.

Back in Lettsom’s day, when an alcoholic hit rock bottom, it was assumed he or she would stay there, a task made easier when the wages of this particular sin included the poor house, a one way ticket to the Botany Bay penal colony, and the gallows.

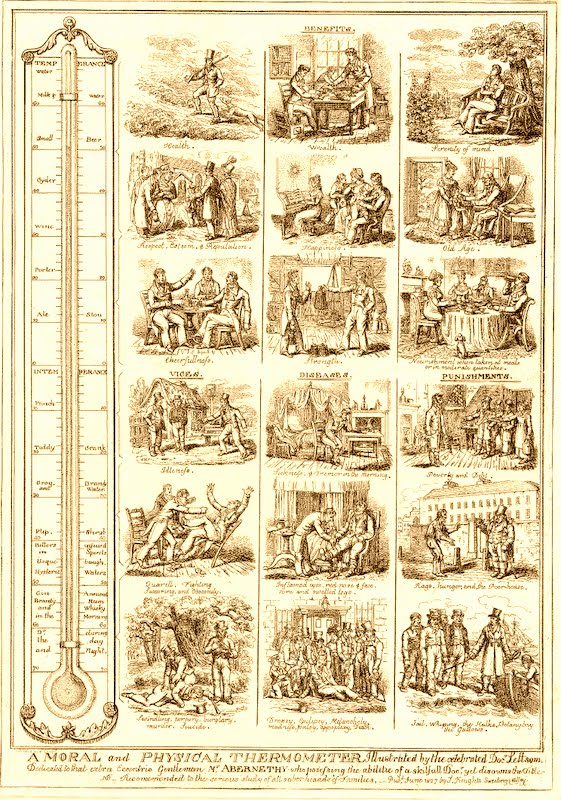

Such looming consequences are easily laughed off when you’ve had a snoot, which may be why Lettsom also published the illustrated version of his thermometer below. A picture is worth a thousand words, particularly when depicting the pre-Dickensian misery that awaits the drunkard and his family.

via Rebecca Onion and Slate

Related Content:

George Washington’s 110 Rules for Civility and Decent Behavior

Thomas Jefferson’s Handwritten Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

“The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink”: An Ad for London’s First Cafe Printed Circa 1652

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday