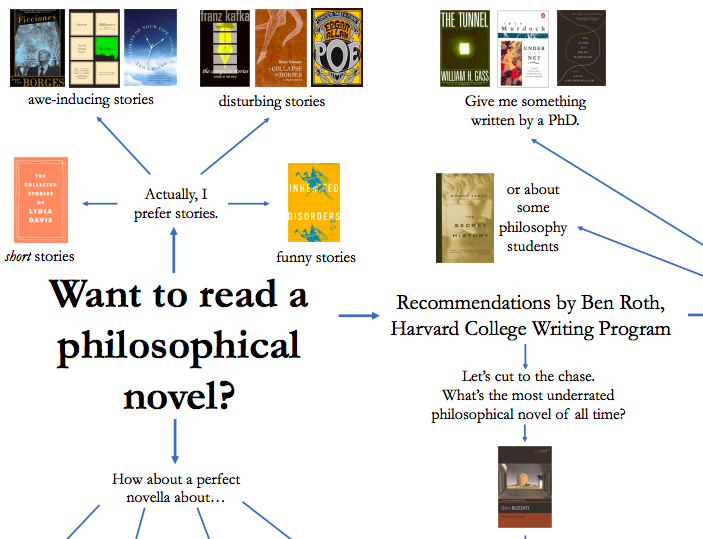

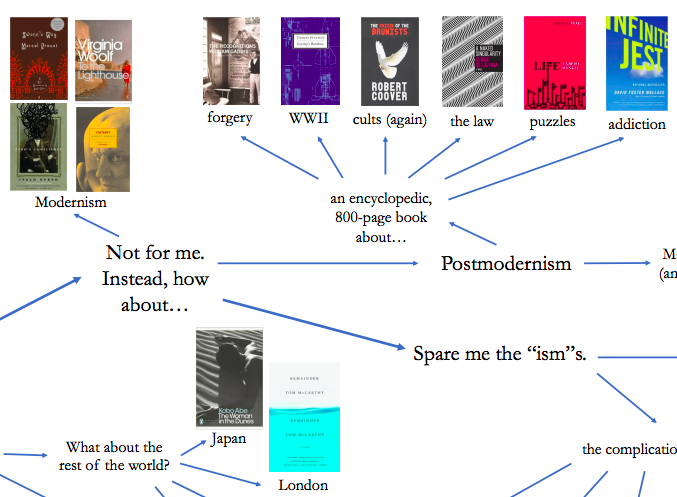

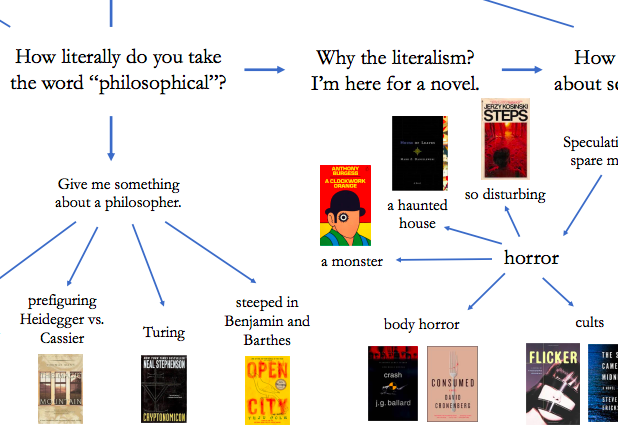

Do you want to read a philosophical novel? Sure, we all do. But the question of exactly what kind of philosophical novel you want to read, let alone which individual book, isn’t quite so easily answered. But now a professional has come to the rescue: “Ben Roth, a philosopher who teaches in the Harvard College Writing Program, has put together a kind of flowchart recommending philosophical novels and stories,” reports Daily Nous’ Justin Weinberg. “With categories like ‘about a philosopher,’ ‘by a Ph.D.,’ ‘horror,’ ‘the complications of history,’ and many more, the chart is pretty big.”

The choices you make in navigating it could land you on the work of a writer from one of a variety of countries, one of several eras, and one of a capacious range of definitions of “philosophical.” If you take the word in the sense of a novel’s being about or steeped in the work of a particular philosopher, Roth recommends books like Thomas Bernhard’s Correction (Wittgenstein) and Teju Cole’s Open City (Benjamin and Barthes). Elsewhere on the map he also includes novels written by philosophically credentialed academics like William Gass, Iris Murdoch, and Anuk Arudpragasam.

If you prefer novels where “fiction writers drop into straight essayistic mode,” Roth offers a choice between the easy mode of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being and the hard mode of Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. (If you just wanted to read about a bunch of philosophy students, well, there’s always Donna Tartt’s The Secret History.)

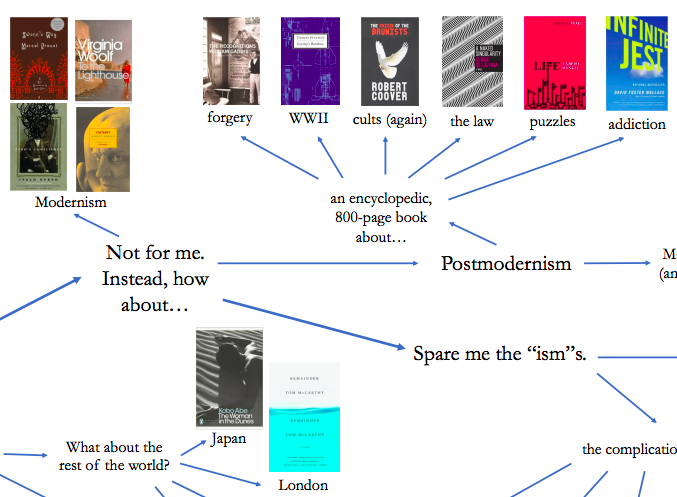

To those who go in for more “novelly novels,” as Geoff Dyer (a known Bernhard enthusiast and author of some pretty philosophical fiction himself) memorably put it, Roth presents more forks in the road: Would you like to read science fiction? Existentialism? Postmodernism? A book free of ‑isms entirely, or anyway as free as possible?

Your answers to those questions and others could have you reading anything from J.G. Ballard’s Crash (“body horror”) to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea (“mid-century French classic”) to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (postmodern, encyclopedic, on addiction). Other choices may lead you to selections less obviously involved with philosophy: J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, or Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Of course, you may not want to read a philosophical novel at all: you may want to read philosophical short stories, in which case Roth recommends such form-defining figures as Edgar Allan Poe, writer of “disturbing stories”; Lydia Davis, writer of “short stories” (emphasis his); and Jorge Luis Borges, writer of “awe-inducing stories.”

Borges and quite a few other names on Roth’s philosophical-novel flowchart also appear in critic David Auerbach’s “Inquest on Left-Brained Literature,” a revealing look at the authors read by “engineers with a literary bent.” Both also include Don DeLillo, whose work Auerbach characterizes as making “heavy use of phantasmagoria, complemented by very sophisticated narrative construction,” and “simple, visceral, classical themes approached in [a] flashy, novel way.” Roth, for his part, describes DeLillo’s White Noise as his “favorite book ever.” Elsewhere on the flowchart, to the philosophical literature enthusiast who’s read everything he offers “the most underrated philosophical novel of all time,” Dino Buzzati’s The Tartar Steppe. No, I haven’t heard of it either, but I have to admit that it keeps good company.

Related Content:

Jorge Luis Borges Selects 74 Books for Your Personal Library

R. Crumb Illustrates Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea: Existentialism Meets Underground Comics

44 Essential Movies for the Student of Philosophy

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.