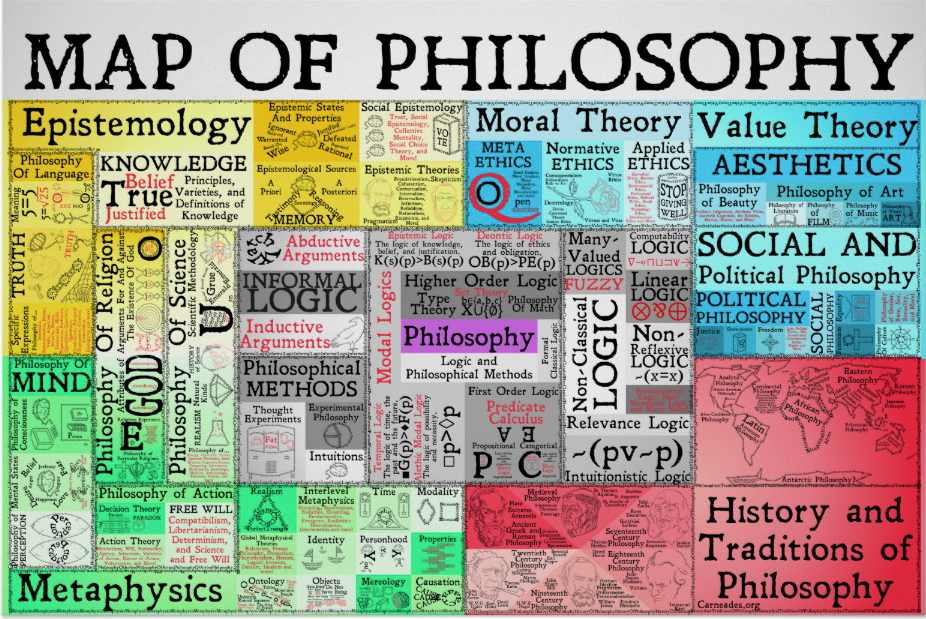

The belief in a singular, coherent “Western tradition” in philosophy has led to a very insular, Eurocentric view in philosophy departments, as Jay L. Garfield and Bryan W. Van Norden write in a New York Times op-ed. “No other humanities discipline demonstrates this systemic neglect of most of the civilizations in its domain,” they argue, “The present situation is hard to justify morally, politically, epistemically or as good educational and research training practice.” In his follow-up book Taking Back Philosophy Van Norden argues that educational institutions should “live up to their cosmopolitan ideals” by expanding the canon and teaching non-Western philosophical traditions.

One philosophy educator, Peter Adamson, professor of philosophy at the LMU in Munich and King’s College London, has taken up the challenge of teaching global philosophical traditions through his popular podcast The History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, with series on the Islamic World, Africana, and India. With expert co-authors and guests, Adamson’s podcasts help us navigate cultural and historical differences without watering down the substance of diverse bodies of thought.

These surveys of non-Western traditions aim to be as exhaustive as the podcast’s coverage of Classical, Later Antiquity, and Medieval periods in Europe. We’ve featured Adamson’s podcasts on Islamic and Indian philosophy in an earlier post. Now we revisit his series on Indian philosophy, which has grown substantially in the interval, from thirty-two to sixty-two episodes, divided into three categories—“Origins,” “Age of the Sutra,” and “Buddhists and Jains.”

Very broadly, much Indian philosophy can be understood as a centuries-long conflict between the six orthodox Vedic schools (astika) and the heterodox (nastika) schools, including Buddhism, Jainism, and Carvaka, a materialist philosophy that denied all metaphysical doctrines. While some strains among these schools of thought can be associated with individual names, like Kanada, Patañjali, or Nagarjuna, much ancient Indian philosophy “is represented by a mass of texts,” as Luke Muehlhauser writes in his short guide, “for which the authors and dates of composition are mostly unknown.”

Adamson’s free podcast survey of Indian philosophy makes for entertaining, informative listening. You can download every episode in .zip form at the links above. Or find links to the individual episodes right below. To keep up with trends in the study of Indian philosophy in English, be sure to follow the Indian Philosophy Blog. And for an excellent list of “Readings on the Less Commonly Taught Philosophies (LCTP),” see this post by Bryan Van Norden here.

Related Content:

Free Online Philosophy Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness