Philosopher and psychoanalyst Slavoj Zizek is a polarizing figure, in and out of the Academy. He has been accused of misogyny and opportunism, and a Guardian columnist once wondered if he is “the Borat of philosophy.” The latter epithet might be as much a reference to his occasional boorishness as to his Slovenian-accented English. Despite (or because of) these qualities, Zizek has become a fascinating public intellectual, in part because all of his work is shot through with pop culture references as diffuse as the most studied of fanboys. And even though Zizek, a student of the Freudian theorist Jacques Lacan, can get deeply obscure with the best of his peers, his enthusiasm and rapid-fire free-associations mark him as a true fan of everything he surveys.

The Zizek I just described is fully in evidence in the short clip above from the three-part documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. Directed by Sophie Fiennes (sister of Joseph and Ralph), The Pervert’s Guide places Zizek in original locations and replica sets of several classic films—David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, and Hitchcock’s Vertigo, to name just a few. Zizek’s scenes of commentary are edited with scenes from the films to give the impression that he is speaking from within the films themselves. It’s a novel approach and works particularly well in the video above, where Zizek gives us his take on Vertigo. As he says of Hitchcock’s film—which could apply to the one he is in as well—“often things begin as a fake, inauthentic, artificial, but you get caught in your own game.” Viewers of The Pervert’s Guide get caught in Zizek’s interpretive game; it’s a fascinating, ridiculous, and unsettling one.

In the clip, through a series of close analyses of plot points and camera angles, Zizek concludes that Vertigo is the realization of a male fantasy, which necessarily involves violence and nightmarish transformations. In the “male libidinal economy,” he says, in the jargon‑y psychoanalytic speak of his trade, women must be “mortified” before they are acceptable sexual partners. Slipping out of academic argot, he clarifies: “to paraphrase an old saying, the only good woman is a dead woman.” It’s this kind of blunt and utterly unsentimental way of speaking that raises the hackles of some of Zizek’s critics. But I’m not here to defend him. Watching (and reading) him for me is a game of edge-of-your seat “what outrageous or incomprehensible thing is he going to say next?” and I’ll admit, I enjoy it. So I’ll leave you with a final Zizek-ism. Perhaps it will scare you off for good, or perhaps you’re game for a few more rounds of “perversion” with this encyclopedic critic of the self, the social, and the sexual:

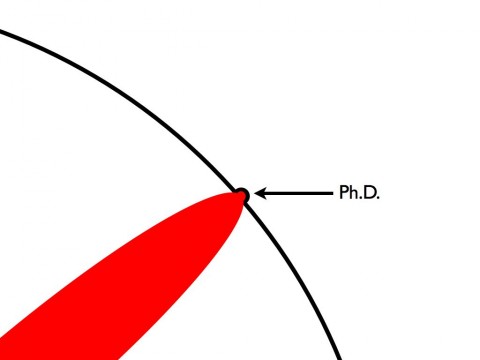

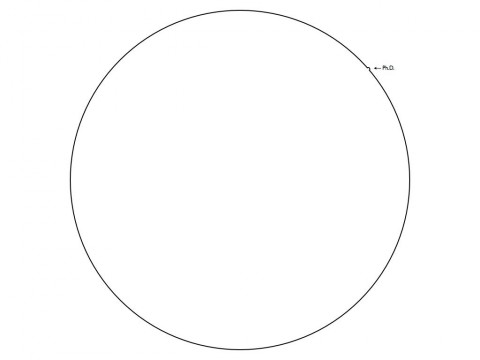

“A subject,” says Zizek, “is a partial something, a face, something we see. Behind it, there is a void, a nothingness. And of course, we spontaneously tend to fill in that nothingness with our fantasies about the wealth of human personality and so on, and so on. To see what is lacking in reality, to see it as that, there you see subjectivity. To confront subjectivity means to confront femininity. Woman is the subject. Masculinity is a fake.”

You can watch the film in its entirety here.

via Biblioklept

Related Content:

Žižek!: 2005 Documentary Reveals the “Academic Rock Star” and “Monster” of a Man

Good Capitalist Karma: Zizek Animated

Slavoj Žižek: How the Marx Brothers Embody Freud’s Id, Ego & Super-Ego

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.