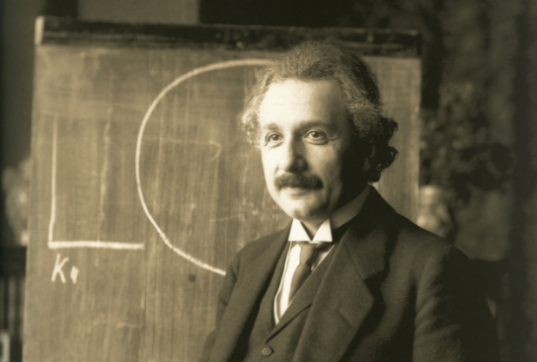

Albert Einstein’s activities as a passionate advocate for peace were well-documented during his lifetime. His celebrity as a famous physicist and one of the world’s most recognizable faces lent a great deal of weight to his pacifism, a view otherwise not given much consideration in the popular press at almost any time in history. However, according to a 2006 book titled Einstein on Race and Racism by Fred Jerome and Roger Taylor, the scientist was also as passionate about combating racism and segregation as he was about combating war. This facet of Einstein’s life was virtually ignored by the media, as was a visit he made in 1946 to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first degree-granting college for African-Americans and the alma mater of Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall.

Invited to Lincoln to receive an honorary degree, Einstein gave a lecture on physics but also bluntly addressed the racial animus that held the country in its grip, reportedly calling racism, “a disease of white people” and saying he “did not intend to be quiet” about his opposition to segregation and racist public policy. Lest anyone think the Nobel-prize-winning physicist was pandering to his audience, the Harvard Gazette offers a comprehensive summary of Einstein’s support of progressive anti-racist causes, including his personal support of members of Princeton’s black community (he paid one man’s college tuition), a town Princeton native Paul Robeson once called “the northernmost town in the south.”

Einstein formed relationships with several prominent black leaders—inviting opera singer Marian Anderson to stay in his home after she was refused a room at the Nassau Inn and appearing as a character witness for W.E.B. Dubois when the latter stood accused of “failing to register as a foreign agent.” But it was his 20-year friendship with Robeson that seems central to his involvement in civil rights causes. The Harvard Gazette writes:

Einstein met Paul Robeson when the famous singer and actor came to perform at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre in 1935. The two found they had much in common. Both were concerned about the rise of fascism, and both gave their support to efforts to defend the democratically elected government of Spain against the fascist forces of Francisco Franco. Einstein and Robeson also worked together on the American Crusade to End Lynching, in response to an upsurge in racial murders as black soldiers returned home in the aftermath of World War II.

At the time of the Gazette article, 2007, a movie about Einstein and Robeson’s friendship was apparently in the works, with Danny Glover as Robeson and Ben Kingsley as Einstein. The project is apparently stalled, but with the upsurge in popular interest in the history of civil rights—with the overturning of the Voting Rights Act and the widespread coverage of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington—perhaps the project will see new life soon. I certainly hope so.

via PourMeCoffee

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

MLK’s Last Days and Final Speech

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness