“And what becomes of all the little boys who never comb their hair? They’re lined up all around the block, on the Nickel over there.” So sings Tom Waits on 1980’s “On the Nickel,” which he originally composed for Ralph Waite’s eponymous feature film, a story of shame, degradation, and good times in the sketchiest part of downtown Los Angeles, through which runs 5th Street — the “Nickel” of the title. That part of town has managed an astonishing cleanup since 1980 (then again, most parts of town have, including the once-seething corner referenced by Heartattack and Vine, the title of Waits’ album from that year) to the point that you’ll now find, just off 5th, the new-wave retro, hipster-friendly Nickel Diner: a favorite eatery of mine, incidentally, but hardly one describable with Waits’ signature rasp, a forcefully resigned instrument tuned to evoke the classically, near-mythologically ragged American life.

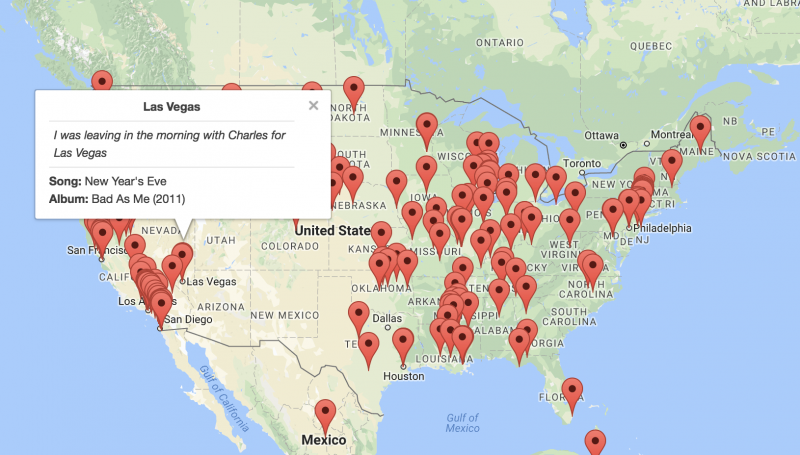

Still, you can find the old Nickel on The Tom Waits Map, which marks out all the lyrically identifiable places in Waits’ America, from Minneapolis’ 9th Street (“Hey Charlie, I’m pregnant and living on the 9th street,” goes “Christmas Card From A Hooker In Minneapolis”) to the state of Idaho (“Danny says we gotta go, gotta go to Idaho, but we can’t go surfing ’cause it’s 20 below,” on “Danny Says”).

We may think of Waits’ artistic persona as a certain lower slice of America made song, but this map, when zoomed out to a global level, reveals references to many exotic lands, as when he sings about “a Hong Kong drizzle on Cuban heels,” from the perspective of a character who “drank with all the Chinamen, walked the sewers of Paris” and of “Radion the human torso, deep from the jungles of Africa.”

The Tom Waits map itself, in fact, comes from an obviously die-hard Swedish fan by the name of Jonas Nordström. As he and the rest of the Waits faithful know, the man doesn’t just speak to an askew sensibility in America; he speaks to askew sensibilities all throughout humanity.

via @sheerly

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Watch Big Time, the Concert Film Capturing Tom Waits on His Best Tour Ever (1988)

Tom Waits’ Classic Appearance on Australian TV, 1979

Tom Waits Reads Charles Bukowski

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.