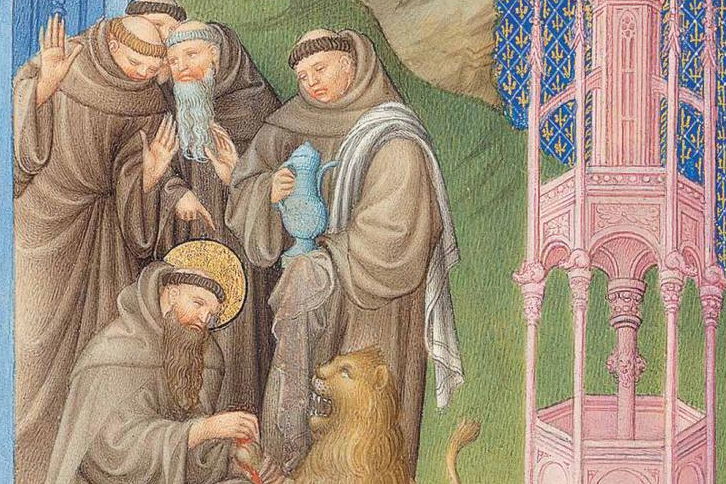

You could pay $118 on Amazon for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s catalog The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. Or you could pay $0 to download it at MetPublications, the site offering “five decades of Met Museum publications on art history available to read, download, and/or search for free.”

If that strikes you as an obvious choice, prepare to spend some serious time browsing MetPublications’ collection of free art books and catalogs.

You may remember that we featured the site a few years ago, back when it offered 397 whole books free for the reading, including American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885–1915; Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomical Drawings from the Royal Library; and Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. But the Met has kept adding to their digital trove since then, and, as a result, you can now find there no fewer than 576 art catalogs and other books besides. Those sit alongside the 400,000 free art images the museum put online last year.

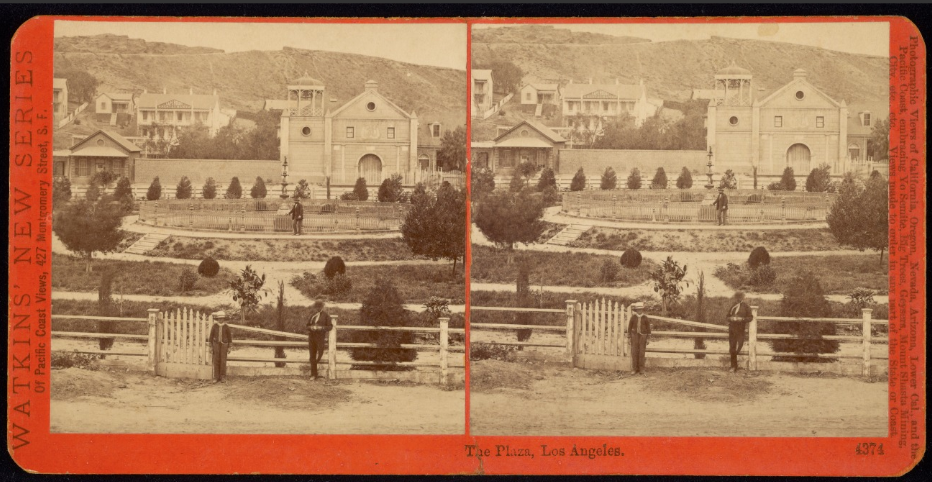

So have a look at MetPublications’ current collection and you’ll find you now have unlimited access to such lush as well as artistically, culturally, and historically varied volumes as African Ivories, Chess: East and West, Past and Present; Modern Design in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1890–1990; Vincent Van Gogh: The Drawings; French Art Deco; or even a guide to the museum itself (vintage 1972).

Since I haven’t yet turned to art collection — I suppose you need money for that — these books don’t necessarily make me covet the vast sweep of artworks they depict and contextualize. But they do make me wish for something even less probable: a time machine so I could go back and see all these exhibits firsthand.

Related Content:

Download Over 250 Free Art Books From the Getty Museum

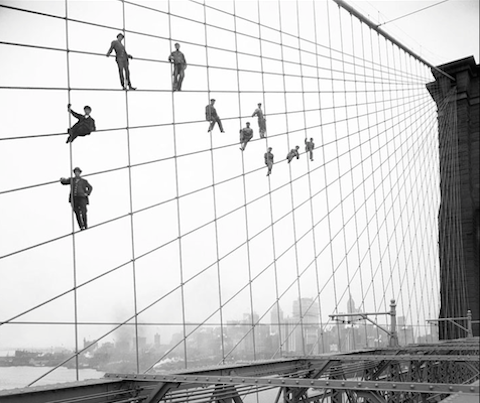

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

The Guggenheim Puts 109 Free Modern Art Books Online

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other DevicesColin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.