“Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?,” asked T.S. Eliot in lines from his play “The Rock.” His prescient description of the dawning information age has inspired data scientists and their dissenters for decades. Thirty-six years after Eliot’s prophetic lament over “Endless invention, endless experiment,” futurist Alvin Toffler described the effects of information overload in his book Future Shock, and though many of his predictions haven’t aged well, his “prognosis,” writes Fast Company, “was more accurate than not.” Among his many “Tofflerisms” is one I believe Eliot would appreciate: “The illiterate of the future will not be the person who cannot read. It will be the person who does not know how to learn.”

Indeed, the exponential accumulation of data and information, and the incredible amount of ready access would make both men’s heads spin. Internet archives grow vaster and vaster, their contents an embarrassing richness of the world’s treasures, and a perhaps even greater store of its obscurities. Each week, it seems, we bring you news of one or two more open access databases filled with images, texts, films, recorded music. It can indeed be dizzying. And of all the archives I’ve surveyed, used in my own research, and presented to Open Culture readers, none has seemed to me vaster than Europeana Collections, a portal of “48,796,394 artworks, artefacts, books, videos and sounds from across Europe,” sourced from well over 100 institutions such as The European Library, Europhoto, the National Library of Finland, University College Dublin, Museo Galileo, and many, many more, including contributions from the public at large. Where does one begin?

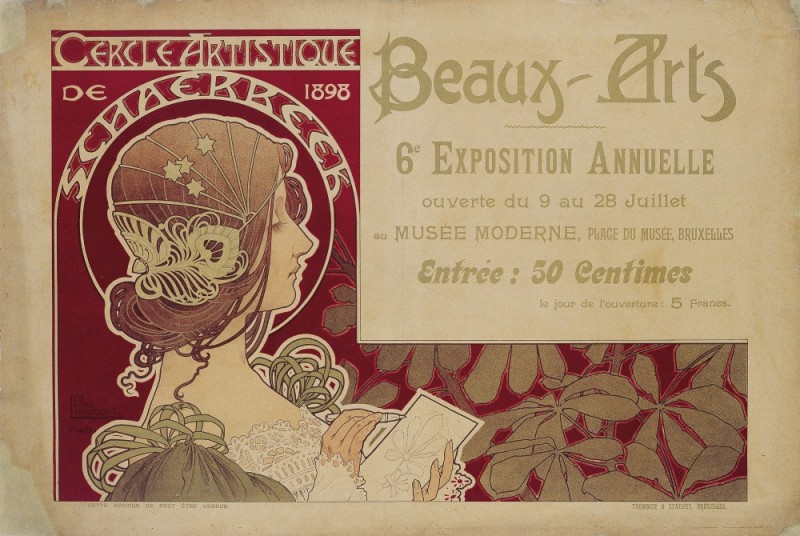

In such an enormous warehouse of cultural history, one could begin anywhere and in an instant come across something of interest, such as the stunning collection of Art Nouveau posters like that fine example at the top, “Cercle Artstique de Schaerbeek,” by Henri Privat-Livemont (from the Plandiura Collection, courtesy of Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalynya, Barcelona). One might enter any one of the available interactive lessons and courses on the history of World War I or visit some of the many exhibits on the period, with letters, diaries, photographs, films, official documents, and war propaganda. One might stop by the virtual exhibit, “Photography on a Silver Plate,” a fascinating history of the medium from 1839–1860, or “Recording and Playing Machines,” a history of exactly what it sounds like, or a gallery of the work of Swiss painter Jean Antoine Linck. All of the artifacts have source and licensing information clearly indicated.

The possibilities may literally be endless, as the collection continues to expand at a rate far beyond the ability of any one person, or team of people, or entire research institute of people to match. It is easy to feel adrift in such a database as this, which stretches on like a Borgesian library, offering room after endless room of visual splendor, documentation, and interpretation. It is also easy to make discoveries, to meet people, stumble upon art, hear music, see photographs, learn histories you would never have encountered if you knew what you were looking for and knew exactly how to find it. Eliot warned us—and rightly so—of the dangers of information overload. But he neglected, in his puritanical way, to describe the pleasures, the minor epiphanies, the happy chance occurrences afforded us by the ever-expanding sea of information in which we swim. One can learn to navigate it, one can drift aimlessly, and one can, simultaneously, feel immensely overwhelmed.

Related Content:

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness