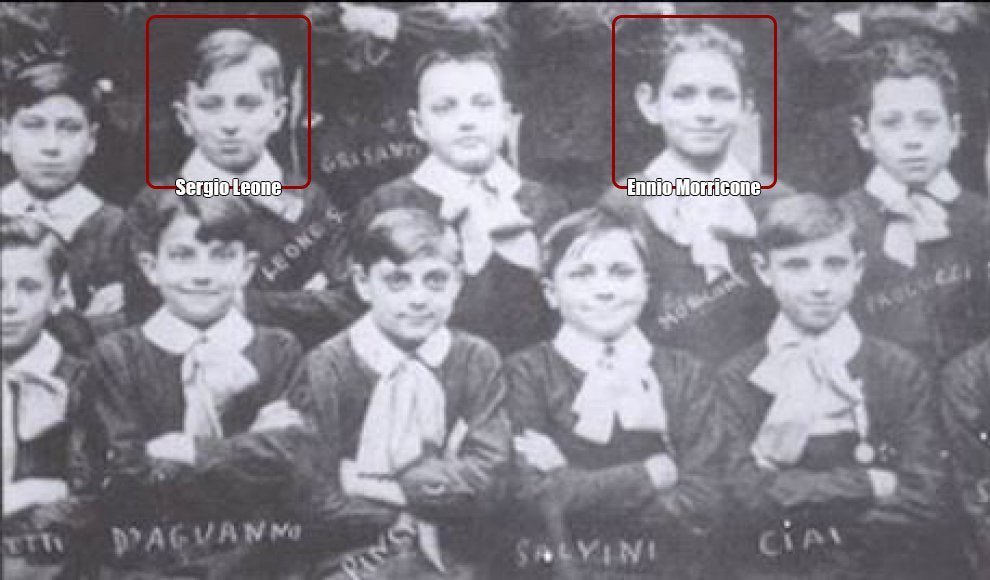

Little did they know where life would take them–and how their futures would be intertwined.

A great find by @ddoniolvalcroze.…

Little did they know where life would take them–and how their futures would be intertwined.

A great find by @ddoniolvalcroze.…

What we think of as “film music” today is a creation of only a few inventive and original composers, one fewer of whom walks the Earth as of yesterday. Though Ennio Morricone will be remembered first for his association with spaghetti western master Sergio Leone, his career in film scores spanned half a century and encompassed work for some of the most acclaimed directors of that period: his countrymen like Michelangelo Antonioni, Bernardo Bertolucci, Pier Paolo Pasolini, but also such commanding Hollywood filmmakers as John Huston, Terrence Malick, and Quentin Tarantino. Morricone didn’t just write music to add to their films; he became a collaborator, without whose work their films would be difficult to imagine.

The result, in pictures from L’Avventura to Salò to Days of Heaven to The Untouchables to The Hateful Eight, is a union of the arts that transcends individual cultures. It doesn’t matter what country you come from, what generation you belong to, whether you enjoy Westerns or indeed cinema itself: you know the theme music Morricone wrote for Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly the moment you hear it.

Whether or not you’ve seen the movie, you’ll appreciate the especially rich performance by the Danish National Symphony Orchestra at the top of the post, part of a 2018 concert called The Morricone Duel, a celebration of “a wide range of western movies and mafia movies reflecting different perspectives on an Italian-American movie and film music style.”

The Morricone Duel’s Youtube playlist includes the Danish National Symphony Orchestra’s renditions of pieces from other Morricone-Leone collaborations like A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, Once Upon a Time in the West, and Once Upon a Time in America. Though the evening also included pieces from The Untouchables and Henri Verneuil’s The Sicilian Clan, many in the audience must have thrilled most when the musicians launched into the overture from The Hateful Eight. They could hardy be more ardent Morricone fans than Tarantino himself, who used pieces from Morricone’s existing Spaghetti-western soundtracks in Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds before making a western of his own, which wouldn’t have been complete without original Morricone music. The Hateful Eight turned out to be Morricone’s penultimate film score, but his influence will resonate through generations of cinema to come — and outlast, no doubt, the western and gangster genres themselves.

Related Content:

The Music in Quentin Tarantino’s Films: Hear a 5‑Hour, 100-Song Playlist

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

If you don’t floss or brush your teeth, they will rot and fall out. If you don’t eat fruits and vegetables, you will get scurvy or some other horrible disease. If you don’t use protection… well, you know the rest. These are facts of life we mostly accept if we care about ourselves and others because they are beyond disputing. But the idea of wearing a cloth mask when in public during a viral pandemic spread through droplets from the nose and mouth—a practice endorsed by the CDC, the World Health Organization, scientists at Stanford, Johns Hopkins, and pretty much every other research university—has become some kind of bizarre culture war.

Maybe some walk around mask-less because they’ve internalized the idea that the coronavirus is “over,” despite the fact it’s spreading at around 50,000 new cases per day in the US, and potentially heading toward double that number. Maybe some feel it won’t affect them because they aren’t elderly or immunocompromised, never mind that viruses mutate, and that the novel (meaning “new”) coronavirus has already demonstrated that it is far less discriminating (in purely biological terms) than previously thought. (In Florida, the median age for COVID-19 has dropped from 65 to 37 years old.) Never mind that spreading the virus, even if one is not personally at high risk, compromises everybody else.

Are masks uncomfortable, especially in hot, humid weather? Do they muffle speech and make it hard to have satisfying face-to-face interactions? Well, yes. But consider your hourlong masked trip to the grocery store against the 12 or 24 or 48 or whatever hour-long shifts medical personnel are pulling in emergency departments across the country.

It really is the least we can do. And we can do it in style—masks went from scarce, with armies of homebound neighbors sewing homely stacks of them, to truly overabundant and fashionable, on the rack of every grocery, pharmacy, and convenience store. It couldn’t be easier.

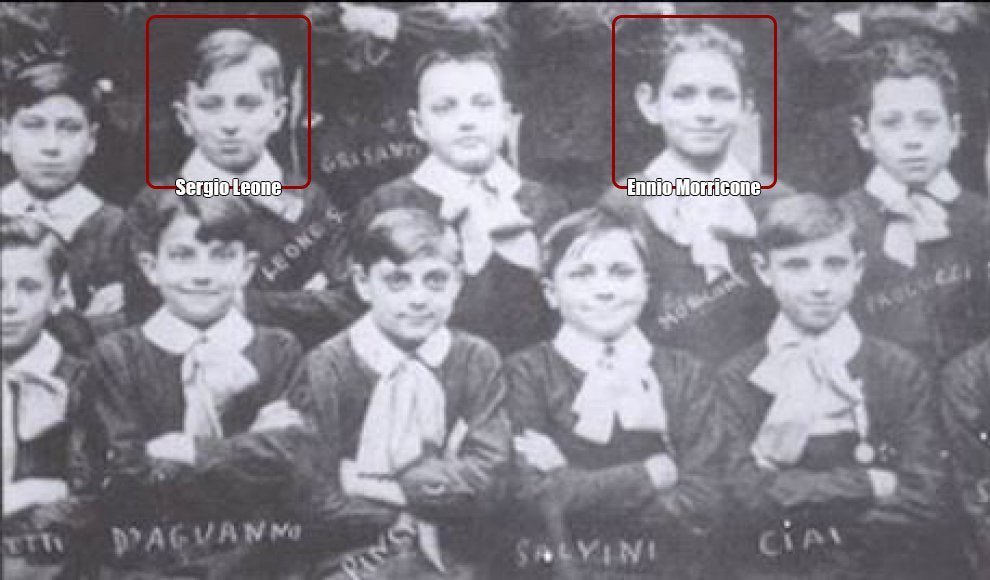

If you’re concerned about looking like every other masked weirdo out there, consider these masks created by Maria Popova of Brain Pickings, which she introduces with references to Rebecca Elson’s poem, “Antidotes to Fear of Death.” The science of public health may demand that we are grimly practical at the moment, but Popova wants to remind us that scientific thinking is equally invested in the experience of awe and the love of life. By wearing these masks, we can communicate to others, those who may be feeling despondent over the sea of masked faces in public places, that there is beauty in the world and we can fully experience if we get through this. Popova’s masks, printed and sold by Society6, illustrate the wonders of scientific curiosity with “wondrous centuries-old astronomical art and natural history illustrations.”

These include “treasures like the Solar System quilt Ella Harding Baker spent seven years crafting… gorgeous 18th-century illustrations from the world’s first encyclopedia of medicinal plants… astonishing drawings of celestial objects and phenomena…trailblazing 18th-century artist Sarah Stone’s stunning illustrations of exotic, endangered, and now-extinct animals; some graphically spectacular depictions of how nature works from a 19th-century French physics textbook; Ernst Haeckel’s heartbreak-fomented drawings of the otherworldly beauty of jellyfish…William Saville Kent’s pioneering artistic-scientific effort to bring the world’s awareness and awe to the creatures of the Great Barrier Reef; and art from the German marine biologist Carl Chun’s epoch-making Cephalopod Atlas — the world’s first encyclopedia of creatures of the deep.”

Society6 is donating a portion of its proceeds to World Center Kitchen, and Popova is donating to The Nature Conservancy. You can purchase your own vintage science illustration mask here and see some of these illustrations in their original context at the links further down.

Antidotes to Fear of Death

Sometimes as an antidote

To fear of death,

I eat the stars.Those nights, lying on my back,

I suck them from the quenching dark

Til they are all, all inside me,

Pepper hot and sharp.Sometimes, instead, I stir myself

Into a universe still young,

Still warm as blood:No outer space, just space,

The light of all the not yet stars

Drifting like a bright mist,

And all of us, and everything

Already there

But unconstrained by form.And sometime it’s enough

To lie down here on earth

Beside our long ancestral bones:To walk across the cobble fields

Of our discarded skulls,

Each like a treasure, like a chrysalis,

Thinking: whatever left these husks

Flew off on bright wings.

Related Content:

The Brilliant Colors of the Great Barrier Revealed in a Historic Illustrated Book from 1893

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Image via YouTube, 1959 interview with Mike Wallace

Finally bowing to public pressure, the Trump administration has revealed which companies received loans from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) created to support small businesses during COVID-19. To no one’s surprise, the published list reportedly includes a host of privileged entities: the shipping business owned by Mitch McConnell’s wife Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao; businesses associated with members of Congress (from both parties); the law firm of David Boies; elite private schools like Sidwell Friends and Saint Ann’s; Grover Norquist’s Anti-Tax Group; the law firm run by Trump’s longtime personal lawyer, Marc E. Kasowitz; billionaire Kanye West’s company, Yeezy; the fine art studio for millionaire sculptor Jeff Koons, a venture that raises money for Trump’s campaign and the RNC, etc.

Add to the list the Ayn Rand Institute–an organization named after Ayn Rand, the Russian writer who exalted the self-reliant individual and criticized social welfare programs that support the vulnerable. As she wrote in The Virtue of Selfishness, “The right to life means that a man has the right to support his life by his own work (on any economic level, as high as his ability will carry him); it does not mean that others must provide him with the necessities of life.” In short, if you can’t make it, you’re on your own.

Rand’s political theory collapses when it confronts everyday reality. At the end of her own life, Rand, suffering from lung cancer, had to grudgingly rely on social security and medicare to make ends meet. Now, reports Reuters, the institute bearing her name has requested (and apparently received) “a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan of up to $1 million.” All while showing no gratitude to the American taxpayer. The Ayn Rand Institute deemed the loan “partial restitution for government-inflicted losses.” (Also see their latest justification here.) Some will consider that spin–a way to justify accepting government largesse.

Watching Ayn Rand talk below, it seems like a principled Randian would have gone, hat in hand, to a private charity instead.

Related Content:

When Ayn Rand Collected Social Security & Medicare, After Years of Opposing Benefit Programs

When Ella Fitzgerald took the stage for the first time at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, “we heard a sound so perfect” that the entire theater went silent, says dancer and choreographer Norma Miller. “You could hear a rat piss on cotton.” Fitzgerald was 17 years old, and she had already faced severe racial discrimination. “Everything was race,” says Miller, describing the de facto segregation in Harlem in the 20s and 30s. “You couldn’t go out of your zone… slavery is over, but you don’t have jobs. So the confinement meant you had to do for yourself.”

In 1917, a 2 year old Fitzgerald had traveled with her mother and stepfather from Newport News, Virginia, where she was born, to Yonkers, New York. They were part of the Great Migration that brought blues and jazz to Northern cities. Fitzgerald grew up sneaking into Harlem’s ballrooms to hear Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Then at age 13, her mother died. Fitzgerald was devastated. She began skipping school and the police arrested her for truancy and sent her to a reform school.

Black girls at the school, writes Nina Bernstein in The New York Times, “were segregated in the two most crowded and dilapidated of the reformatory’s 17 ‘cottages,’ and were routinely beaten by male staff. There was a fine music program at the school, but Ella Fitzgerald was not in the choir: it was all white.” Fitzgerald escaped and made her way back to Harlem, where she slept on the streets. She stepped onstage at the Apollo’s amateur night as part of a dare and had originally planned to do a dance routine.

The year after her Apollo debut, Fitzgerald performed at Yale University with Chick Webb’s orchestra. She released her first single, one of the biggest records of the decade, in 1938. In 1939, she took over as bandleader and carved out a career in the following years that included tours in Japan, Europe, and Australia, where she became a huge sensation in 1954. In the states, however, she was still treated like a criminal. She missed her first two shows in Sydney because she and her pianist, assistant, and manager Norman Granz were thrown off the plane in Honolulu without explanation or recourse. (Fitzgerald later sued and won, as she explains in a 1970 CBC interview clip above.)

In 1955, Fitzgerald’s career received a major boost when Marilyn Monroe pressured the owner of Sunset Strip’s famed Mocambo to book the singer. “After that, I never had to play a small jazz club again,” Fitzgerald later recalled. That same year, reports USA Today, “she was arrested in her dressing room at an integrated show in Houston. When she arrived at the police station, an officer asked for her autograph, Fitzgerald recalls.” She rose above the ugliness with poise and grace and mostly preferred not to talk about it, though it surely took its toll. “She lived, she survived,” says cultural critic Margo Jefferson. “She became famous and she kept on keeping on—at what inner price, we don’t know.”

We do, however, have a slightly better sense of how she felt thanks to clips from a 1963 interview with New York radio host Fred Robbins that have emerged after going unheard for decades (beginning at :30 in the video at the top). Discussing her frustration with segregation in the South, she says:

Maybe I’m stepping out (of line), but I have to say it, because it’s in my heart. It makes you feel so bad to think we can’t go down through certain parts of the South and give a concert like we do overseas, and have everybody just come to hear the music and enjoy the music because of the prejudice thing that’s going on.

I used to always clam up because you (hear people) say, ‘Oh, gee, show people should stay out of politics.’ But we have traveled so much and been embarrassed so much. (Fans) can’t understand why you don’t play in Alabama, or (ask), ‘Why can’t you have a concert? Music is music.’

The situation was truly “embarrassing,” as she put it, for the country and for her and her fellow musicians. Fitzgerald had seen enough in her life at that point to understand how deeply entrenched racism could become. Hopeful about the future, she also recognized that there were some minds that would never change. “The die-hards, they’re just going to die hard,” she says. “They’re not going to give in. You’ve got to try and convince the younger ones, they’re the ones who’ve got to make the future and those are the ones we’ve got to worry about. Not those die-hards.”

Robbins had promised Fitzgerald that the interview would air “all over the world.” Instead, for reasons unknown, it was shelved and forgotten until author Reggie Nadelson discovered the recording in 2018 at the Paley Center for Media. Despite her reticence to speak out, Fitzgerald was grateful for the opportunity, even if it might end up costing her. “I really ran my mouth,” she says, worrying, “Is it going down South? You think they’re going to break my records up when they hear it? This is unusual for me.” Nonetheless, she says, “I’m so happy that you had me, because instead of singing, for a change I got a chance to get a few things off my chest. I just a human being.”

The clip at the top comes from a new documentary titled Ella Fitzgerald: Just One of Those Things. Watch the trailer for the film above.

Related Content:

How Marilyn Monroe Helped Break Ella Fitzgerald Into the Big Time (1955)

Ella Fitzgerald Sings ‘Summertime’ by George Gershwin, Berlin 1968

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

For more than 200 years, the rulers of Japan kept the country all but closed to the outside world. In 1854, the “Black Ships” of American commander Matthew Perry arrived to demand an end to Japanese isolation — and a commencement of Japanese world trade. Within decades, many fashion-forward Europeans and even Americans couldn’t get enough things Japanese, especially the art, crafts, and clothing that exemplified kinds of beauty they’d never known before. (Vincent van Gogh was a particularly avid fan.) But if Japan changed the West, the West transformed Japan, a process fully in effect in the footage above, shot on the streets of Tokyo between 1913 and 1915.

These scenes may look familiar to dedicated Open Culture readers, and indeed, we previously featured another version of this film back in 2018. With its speed corrected to remove the herky-jerkiness common to old films and with background noise added, these glimpses of the men, women, and many children of the Japanese capital, all of them living between the inward-looking tradition of their country as it had been and the onrush of modernity from without, already felt realistic.

But now you may feel you’ve been personally transported to this culturally and economically heady time in the Land of the Rising Sun thanks to the work of Denis Shiryaev, a Youtuber who specializes in enlarging and restoring vintage film clips with artificial intelligence.

Shirayev is also responsible for the enhanced versions of scenes from Belle Époque Paris, czarist Moscow, Victorian England, New York City in 1911, and even the Lumière Brothers’ early motion picture The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station. At the beginning of this video he reveals the stages of the process that brought this century-old footage of Tokyo to greater vividness: de-noising and damage removal, colorization, facial restoration, and upscaling to 4K resolution at 60 frames per second — all assisted by neural networks that, “trained” on relevant visual materials new and old, crisp and weathered, to determine the best ways to make it all look more convincing. The results may make you wonder what else will soon be possible — surely not a feeling unknown to these early 20th-century Tokyoites.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

By the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it seemed the fate of the Soviet Union was all but sealed. It would be two more years before the USSR officially dissolved, and flew the Soviet flag over the Kremlin for the last time, but the age of Cold War belligerence officially ended with the 1980s, so it seemed. Soft power and suasion would finish the job. And what better way to announce this transition than with the soft-rock stylings of a power ballad like the Scorpions’ “Wind of Change”? The sentimental song from German metal and hard rock favorites was suddenly inescapable in 1990, and it was not at all subtle about its message.

The song became a massive hit and remains one of the best-selling singles of all time. It served as “a soundtrack of sorts to a political and cultural revolution,” writes Richard Bienstock at Rolling Stone. Oddly, “especially in light of the Scorpions’ background… ‘Wind of Change’ was about neither the Berlin Wall nor their German homeland.” Instead, the song was ostensibly inspired by a historic two-day festival the band played in Moscow in 1989, a so-called “hard-rock Woodstock” featuring metal royalty like Ozzy Osbourne, Mötley Crüe, Cinderella, and Skid Row alongside hard rock Soviet bands like Gorky Park.

Three months after the concert, the Berlin Wall fell, and Scorpions’ lead singer Klaus Meine wrote the words:

The world is closing in

Did you ever think

That we could be so close, like brothers

The future’s in the air

I can feel it everywhere

Blowing with the wind of change

The iconic whistled intro and lighters-in-the-air video cemented “Wind of Change” as a definitive statement on how the “children of tomorrow” will “share their dreams” in a globalized world. Tantalizingly vague, the lyrics read like Surrealist ad copy, sliding back and forth between doggerel and weird Symbolist incantation:

The wind of change

Blows straight into the face of time

Like a stormwind that will ring the freedom bell

For peace of mind

Let your balalaika sing

What my guitar wants to say

These lines, it may not shock you to learn, may have been written by the CIA. At least, “that’s the mystery driving the new eight-part podcast series Wind of Change,” writes Nicholas Quah at Vulture. (Listen on Apple, Spotify, Google, and on the podcast website.) “Led by New Yorker staff writer Patrick Radden Keefe and produced by Pineapple Street’s Henry Molofsky… the journey takes us to a shape-shifting Wonderland, a world where an American agency like the CIA may very well have participated in the production of pop culture as part of concerted efforts to build sentiment against its enemies abroad. It might even be something that’s happening right now.”

Those who’ve read about how the Agency has influenced everything from Abstract Expressionism, to literary magazines, creative writing, and Hollywood films might not find these allegations particularly surprising, but as with all the best examples of the serial podcast form, it’s the journey, not the destination that makes this story worth pursuing. Keefe approaches the subject with a naiveté that might be deliberate, playing up the idea of mass entertainment as “carefully devised and calibrated messaging.”

The podcast is great fun (“it’s been described as This is Spinal Tap meets All the President’s Men,” writes Deadline); its story, Keefe says in a statement, “stretches across musical genres, and across borders and periods of history.” Do we ever find out for sure whether the agency best known for overthrowing governments it doesn’t like wrote the Scorpions’ 1990 power ballad “Wind of Change”? “Hear the music, and the accents and the voices,” says Keefe, “and judge for yourself who might be lying and who is telling the truth.”

If you ask Klaus Meine, it’s all a fantasy. (But, then, he would say that, wouldn’t he?) “It’s weird,” the Scorpions singer commented after learning about Keefe’s podcast. “In my wildest dreams I can’t think about how that song would connect with the CIA.” The idea, however, would make “a good idea for a movie,” he says, “That would be cool.” A movie, maybe, funded by the CIA.

Related Content:

How the CIA Helped Shape the Creative Writing Scene in America

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

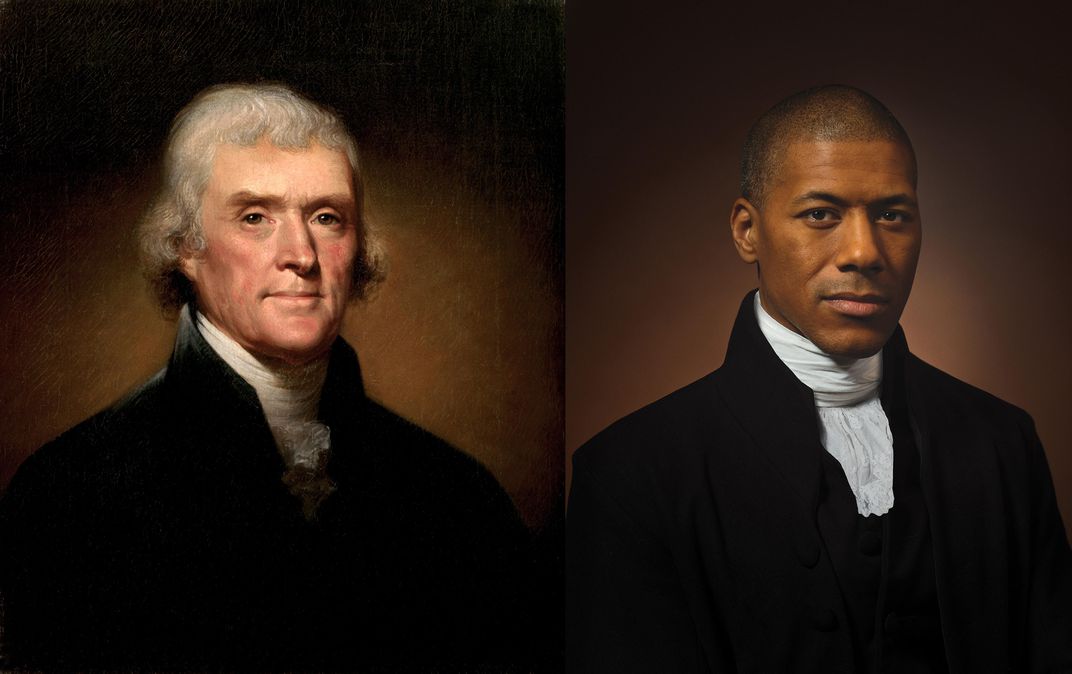

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness… —Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States of America

He was a brilliant man who preached equality, but he didn’t practice it. He owned people. And now I’m here because of it. —Shannon LaNier, co-author of Jefferson’s Children: The Story of One American Family

Many of the American participants in photographer Drew Gardner’s ongoing Descendants project agreed to temporarily alter their usual appearance to heighten the historic resemblance to their famous ancestors, adopting Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s lace cap and sausage curls or Frederick Douglass’ swept back mane.

Actor and television presenter Shannon LaNier submitted to an uncomfortable, period-appropriate neckwrap, tugged into place with the help of some discreetly placed paperclips, but skipped the wig that would have brought him into closer visible alignment with an 1800 portrait of his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Thomas Jefferson.

“I didn’t want to become Jefferson,” states LaNier, whose great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother, Sally Hemings, was written out of the narrative for most of our country’s history.

An enslaved half-sister of Jefferson’s late wife, Martha, Hemings was around sixteen when she bore Jefferson’s first child, as per the memoir of her son, Madison, from whom LaNier is also directly descended.

She has been portrayed onscreen by actors Carmen Ejogo and Thandie Newton (and Maya Rudolph in an icky Saturday Night Live skit.)

But there are no photographs or painted portraits of her, nor any surviving letters or diary entries. Just two accounts in which she is described as attractive and light-skinned, and some political cartoons that paint an unflattering picture.

The mystery of her appearance might make for an interesting composite portrait should the Smithsonian, who commissioned Gardner’s series, seek to entice all of LaNier’s female and female-identifying cousins from the Hemings line to pose.

While LaNier was aware of his connection to Jefferson from earliest childhood, his peers scoffed and his mother had to take the matter up with the principal after a teacher told him to sit down and stop lying. As he recalled in an interview:

When they didn’t believe me, it became one of those things you stop sharing because, you know, people would make fun of you and then they’d say, “Yeah, and I’m related to Abraham Lincoln.”

His family pool expanded when Jefferson’s great-great-great-great-grandson, journalist Lucian King Truscott IV—whose fifth great-grandmother was Martha Jefferson—issued an open invitation to Hemings’ descendants to be his guests at a 1999 family reunion at Monticello.

It would be another 20 years before the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Monticello tour guides stopped framing Hemings’ intimate connection to Jefferson as mere tattle.

Now visitors can find an exhibit dedicated to her life, both online and in the recently reopened house-museum.

Truscott lauded the move in an essay on Salon, published the same week that a yearbook photo of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam in blackface posing next to a figure in KKK robes began to circulate:

Monticello is committing an act of equality by telling the story of slave life there, and by extension, slave life in America. When my cousins in the Hemings family stand up and proudly say, we are descendants of Thomas Jefferson, they are committing an act of equality…. The photograph you see here is a picture of who we are as Americans. One day, a photograph of two cousins, one black and one white, will not be seen as unusual. One day, acts of equality will outweigh acts of racism. Until that day, however, Shannon and I will keep fighting for what’s right. And one day, we will win.

Watch a video of Jefferson descendant Shannon Lanier’s session with photographer Drew Gardner here.

See more photos from Gardner’s Descendents project here.

Read historian Annette Gordon-Reed’s New York Times op-ed on the complicated Hemings-Jefferson connection here.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.