We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness… —Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States of America

He was a brilliant man who preached equality, but he didn’t practice it. He owned people. And now I’m here because of it. —Shannon LaNier, co-author of Jefferson’s Children: The Story of One American Family

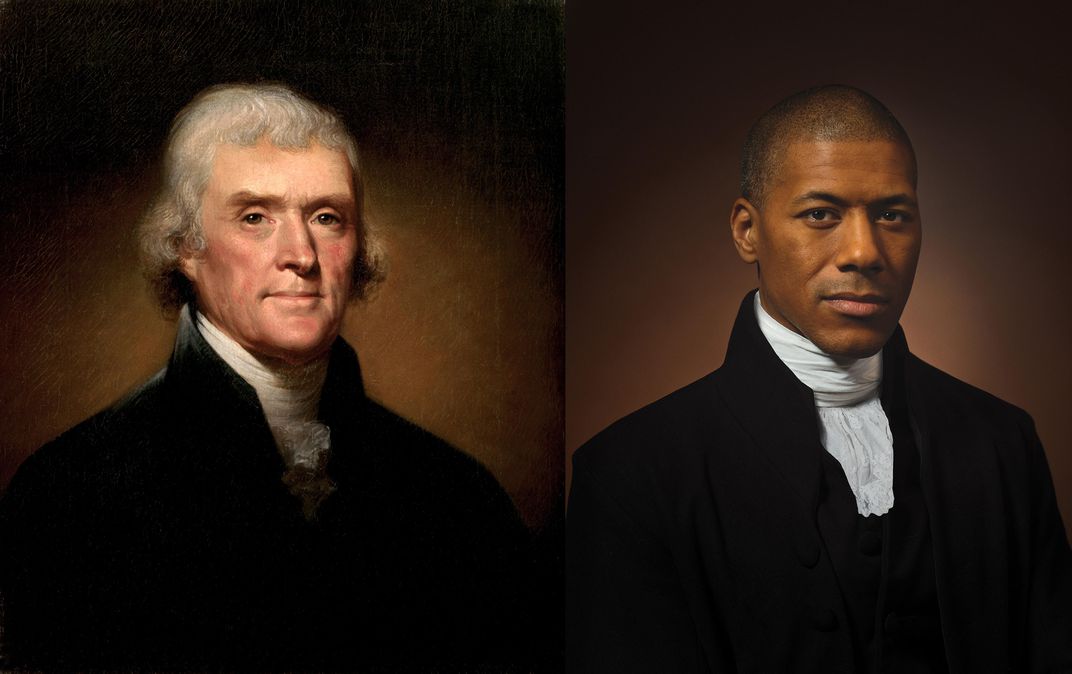

Many of the American participants in photographer Drew Gardner’s ongoing Descendants project agreed to temporarily alter their usual appearance to heighten the historic resemblance to their famous ancestors, adopting Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s lace cap and sausage curls or Frederick Douglass’ swept back mane.

Actor and television presenter Shannon LaNier submitted to an uncomfortable, period-appropriate neckwrap, tugged into place with the help of some discreetly placed paperclips, but skipped the wig that would have brought him into closer visible alignment with an 1800 portrait of his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, Thomas Jefferson.

“I didn’t want to become Jefferson,” states LaNier, whose great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother, Sally Hemings, was written out of the narrative for most of our country’s history.

An enslaved half-sister of Jefferson’s late wife, Martha, Hemings was around sixteen when she bore Jefferson’s first child, as per the memoir of her son, Madison, from whom LaNier is also directly descended.

She has been portrayed onscreen by actors Carmen Ejogo and Thandie Newton (and Maya Rudolph in an icky Saturday Night Live skit.)

But there are no photographs or painted portraits of her, nor any surviving letters or diary entries. Just two accounts in which she is described as attractive and light-skinned, and some political cartoons that paint an unflattering picture.

The mystery of her appearance might make for an interesting composite portrait should the Smithsonian, who commissioned Gardner’s series, seek to entice all of LaNier’s female and female-identifying cousins from the Hemings line to pose.

While LaNier was aware of his connection to Jefferson from earliest childhood, his peers scoffed and his mother had to take the matter up with the principal after a teacher told him to sit down and stop lying. As he recalled in an interview:

When they didn’t believe me, it became one of those things you stop sharing because, you know, people would make fun of you and then they’d say, “Yeah, and I’m related to Abraham Lincoln.”

His family pool expanded when Jefferson’s great-great-great-great-grandson, journalist Lucian King Truscott IV—whose fifth great-grandmother was Martha Jefferson—issued an open invitation to Hemings’ descendants to be his guests at a 1999 family reunion at Monticello.

It would be another 20 years before the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Monticello tour guides stopped framing Hemings’ intimate connection to Jefferson as mere tattle.

Now visitors can find an exhibit dedicated to her life, both online and in the recently reopened house-museum.

Truscott lauded the move in an essay on Salon, published the same week that a yearbook photo of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam in blackface posing next to a figure in KKK robes began to circulate:

Monticello is committing an act of equality by telling the story of slave life there, and by extension, slave life in America. When my cousins in the Hemings family stand up and proudly say, we are descendants of Thomas Jefferson, they are committing an act of equality…. The photograph you see here is a picture of who we are as Americans. One day, a photograph of two cousins, one black and one white, will not be seen as unusual. One day, acts of equality will outweigh acts of racism. Until that day, however, Shannon and I will keep fighting for what’s right. And one day, we will win.

Watch a video of Jefferson descendant Shannon Lanier’s session with photographer Drew Gardner here.

See more photos from Gardner’s Descendents project here.

Read historian Annette Gordon-Reed’s New York Times op-ed on the complicated Hemings-Jefferson connection here.

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Fine art and reality TV are typically rated our highest and lowest forms of entertainment, yet creative competition shows combine the two.

Fine art and reality TV are typically rated our highest and lowest forms of entertainment, yet creative competition shows combine the two.