Back before the public came to terms with the grim causal relationship between cigarettes and cancer, smoking was a jolly affair, whose pleasures extended well beyond the physical act.

Smoking was sociable. Yes, there were certain situations in which three on a match could spell doom, but a far greater likelihood that lighting an attractive stranger’s coffin nail might kindle conversation, and more.

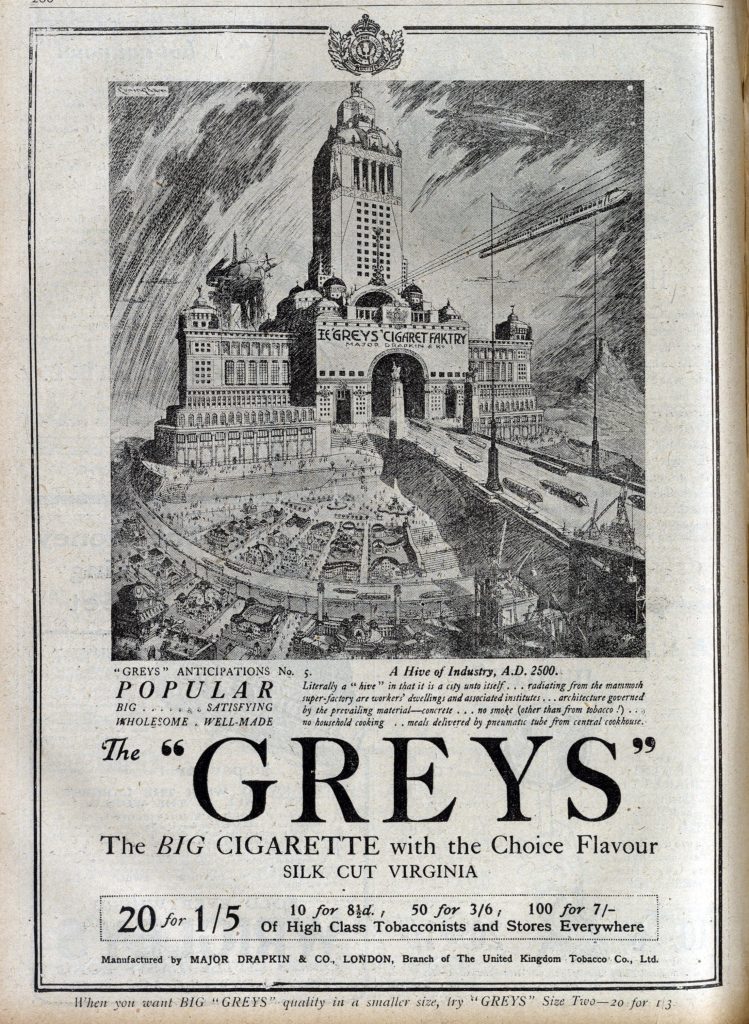

If you were at a loss for words, you might break the ice with the trading cards manufacturers slipped inside cigarette packs, such as these mid-30s beauties that came inside packs of Greys, a now-defunct British cigarette brand, and favorite of WWI vets.

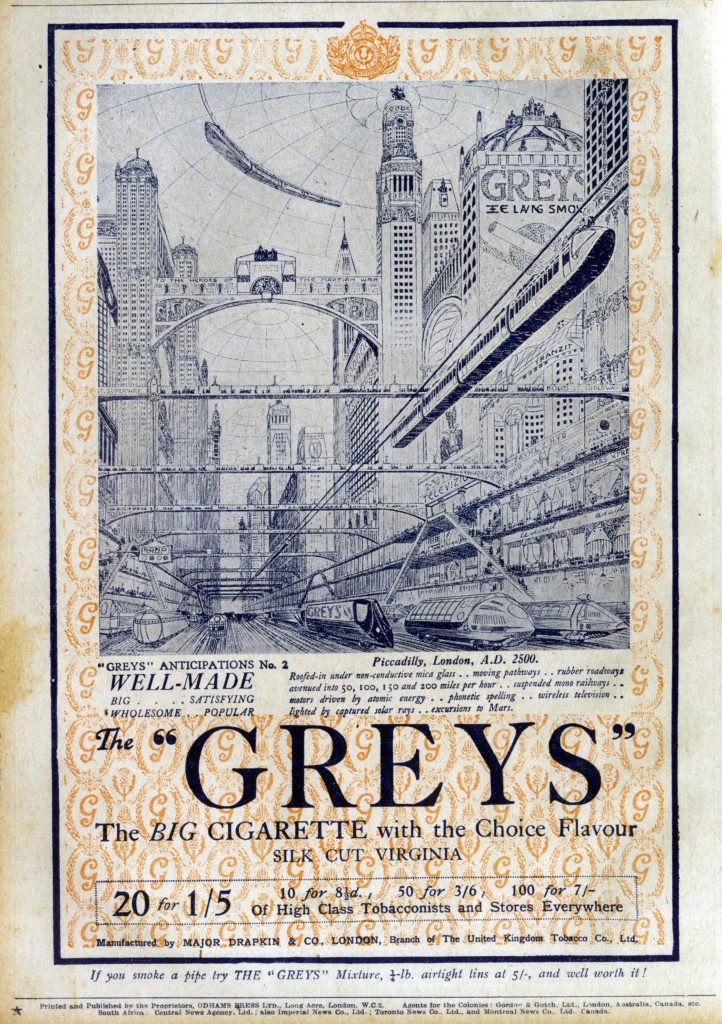

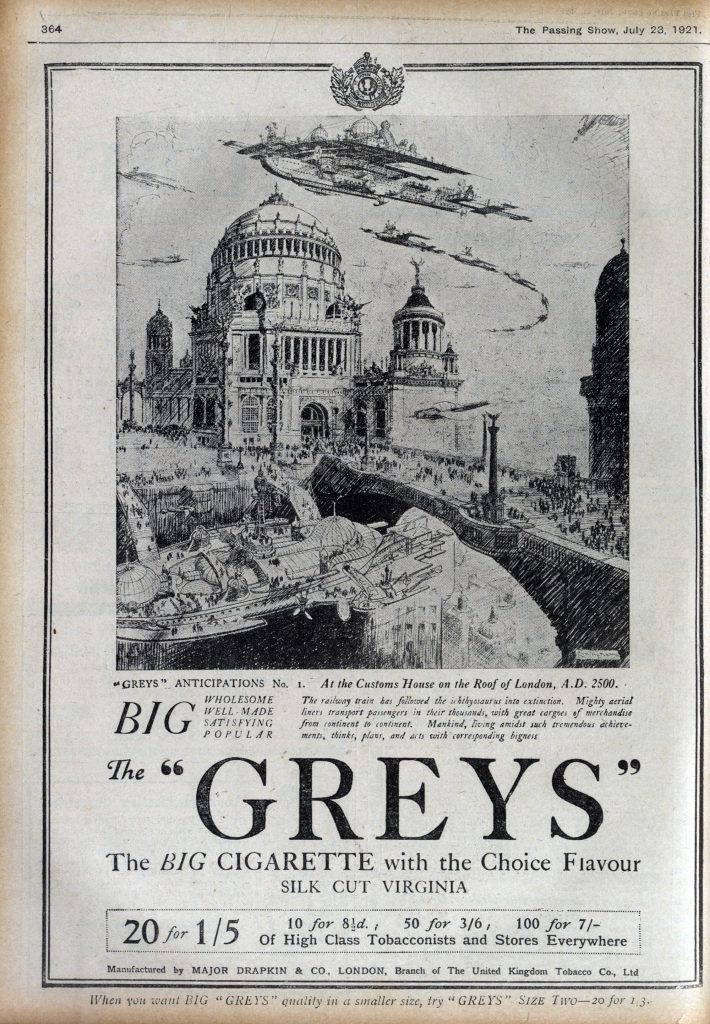

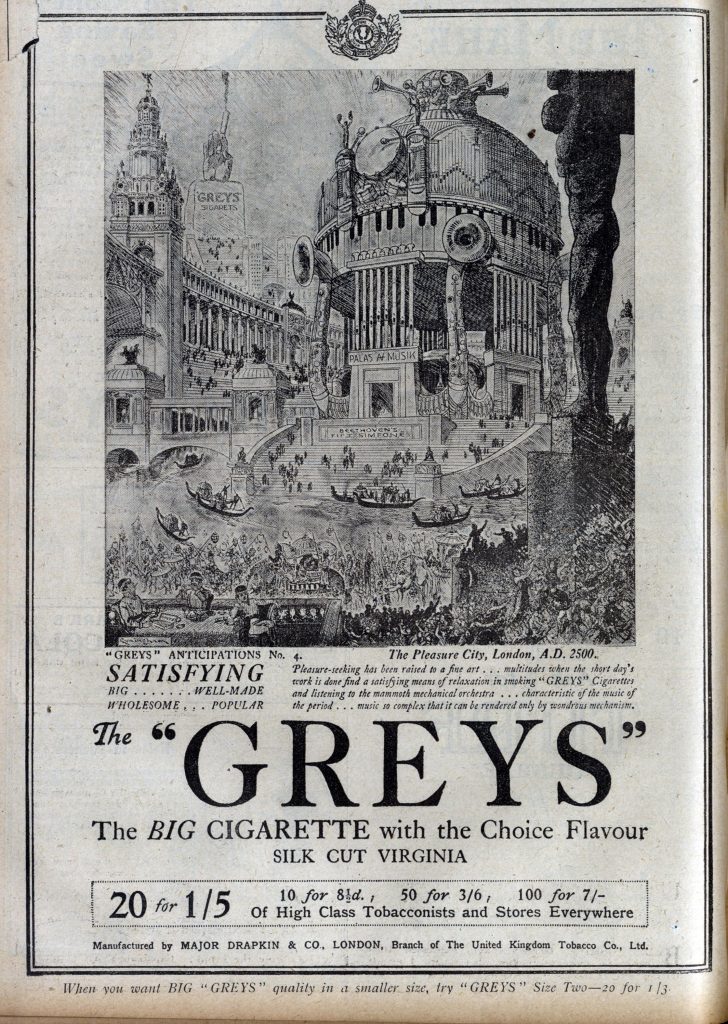

The subject is unusual. Sports, cinema stars, and military scenes were common themes of the time. The “Greys Anticipations” series took creative liberties, by imagining a (cancer-free) year 2500, in which Londoners would be privy to such innovations as solar-lighting, moving sidewalks, and wireless television…

Great Scott! Were they psychic!?

Hopefully not.

Hopefully, we’ve still got 484 years to find out…

“Picadilly, London, A.D. 2500: Roofed-in under non-conductive mica glass . . moving pathways . . rubber roadways avenued into 50, 100, 150 and 200 miles per hour . . suspended mono railways . . motors driven by atomic energy . . phonetic spelling . . wireless television . . lighted by captured solar rays . . excursions to Mars.”

I’m fine with excursions to Mars and monorails but atomic energy is as problematic as the health claims once put forward by cigarette ads.

“At the Customs House on the Roof of London, A.D. 2500: The railway train has followed the ichthyosaurus into extinction. Mighty aerial liners transport passengers in their thousands, with great cargoes of merchandise from continent to continent. Mankind, living amidst such tremendous achievements, thinks, plans, and acts with corresponding bigness.”

Hmm…I was kind of rooting for train travel to make a comeback…

“The Pleasure City, London, A.D. 2500: Pleasure-seeking has been raised to a fine art … mutitudes when the short day’s work is done find a satisfying means of relaxation in smoking “GREYS” Cigarettes and listening to the mammoth mechanical orchestra … characteristic of the music of the period … music so complex that it can be rendered only by wonderous mechanism.”

This does sound rather fun, depending on who’s doing the programming… perhaps we should just stick with headphones and a busker on every corner.

A Hive of Industry, A.D. 2500: Literally a “hive” in that it is a city unto itself … radiating from the mammoth super-factory are workers’ dwellings and associated institutes … architecture governed by the prevailing material — concrete … no smoke (other than from tobacco!) … no household cooking . . meals delivered by pneumatic tube from central cookhouse.

Um…I strongly suggest revisiting Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film, Brazil, before signing off on the whole pneumatic tube thing.

Darran Anderson, author of Imaginary Cities, took a closer look at one of the cards in the above talk about imaginary London. I share his opinion that “phonetic spelling… is the best thing that they envisaged of the future.”

He also notes that the card is about 20 years ahead of its time in promoting a mid-50s‑style vision of the future, but that it failed to predict the demise of Greys Cigarettes, by prominently advertising them on the side of a suspended monorail.

Hubris!

via Metafilter

Related Content:

In 1900, Ladies’ Home Journal Publishes 28 Predictions for the Year 2000

Nikola Tesla’s Predictions for the 21st Century: The Rise of Smart Phones & Wireless, The Demise of Coffee, The Rule of Eugenics (1926/35)

Cigarette Commercials from David Lynch, the Coen Brothers and Jean Luc Godard

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday