“Once upon a time, artists had jobs,” writes Katy Waldman in a recent New York Times Magazine piece. “Think of T.S. Eliot, conjuring ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) by night and overseeing foreign accounts at Lloyds Bank during the day, or Wallace Stevens, scribbling lines of poetry on his two-mile walk to work, then handing them over to his secretary to transcribe at the insurance agency where he supervised real estate claims.” Or Willem de Kooning painting signs, James Dickey writing slogans for Coca-Cola, William Carlos Williams writing prescriptions, Philip Glass installing dishwashers – the list goes on.

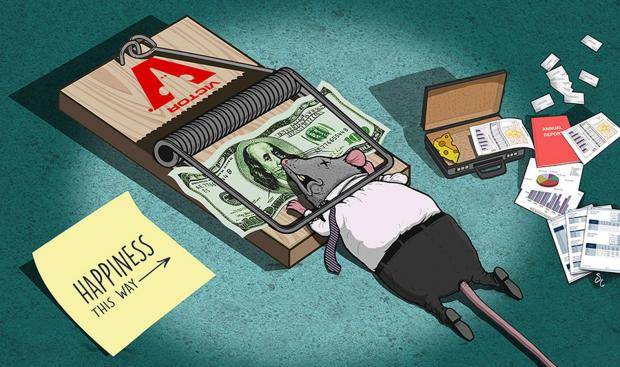

Waldman suggests that we consider day jobs not just bill-paying grinds but delivery systems for “the same replenishing ministries as sleep or a long run: relieving creative angst, restoring the artist to her body and to the texture of immediate experience.” Brian Eno thinks differently. “I often get asked to come and talk at art schools,” he says in the clip above, “and I rarely get asked back, because the first thing I always say is, ‘I’m here to persuade you not to have a job.’ ”

That doesn’t mean, he emphasizes, that you should “try not to do anything. It means try to leave yourself in a position that you do the things you want to do with your time, and where you take maximum advantage of whatever your possibilities are.”

Easier said than done, of course, which is why Eno wants to “work to a future where everybody is in a position to do that,” enacting some form of universal basic income, the general idea of which holds that society will function better if it guarantees all its members a certain standard of living regardless of employment status. But if that standard rises too high, might it run the risk of softening the rigors and loosening the limitations needed to encourage true creativity? Musician Daniel Lanois, who has worked with Eno on the production of several U2 albums as well as ambient music projects, describes learning that lesson from his collaborator in the Louisiana Channel video just above.

“At the peak of my sonic experimentations with Brian Eno, we only ever used four boxes,” says Lanois. “That’s when we started getting these really beautiful textures and human-like sounds from machines. We got to be experts at those few tools.” The limitations under which they worked in the studio may not have followed from any particular philosophy, but the actual experience taught them how a richer artistic result can arise, paradoxically, from more straitened circumstances. Since the beginning of art, its practitioners have always had to find innovative ways around obstacles, whether those obstacles have to do with technology, sides, time, money, or anything else besides. As Lanois reassuringly puts it, “I can imagine that if you have limitation, even financial limitation, that might be okay, man.”

Related Content:

William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

The Genius of Brian Eno On Display in 80 Minute Q&A: Talks Art, iPad Apps, ABBA, & MoreBrian Eno on Why Do We Make Art & What’s It Good For?: Download His 2015 John Peel Lecture

The Employment: A Prize-Winning Animation About Why We’re So Disenchanted with Work Today

Hear Alan Watts’s 1960s Prediction That Automation Will Necessitate a Universal Basic Income

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.