The average person believes implicitly that the photograph cannot falsify. Of course, you and I know that this unbounded faith in the integrity of the photograph is often rudely shaken, for, while photographs may not lie, liars may photograph. —Lewis Wickes Hine, “Social Photography: How the Camera May Help in the Social Uplift” (1909)

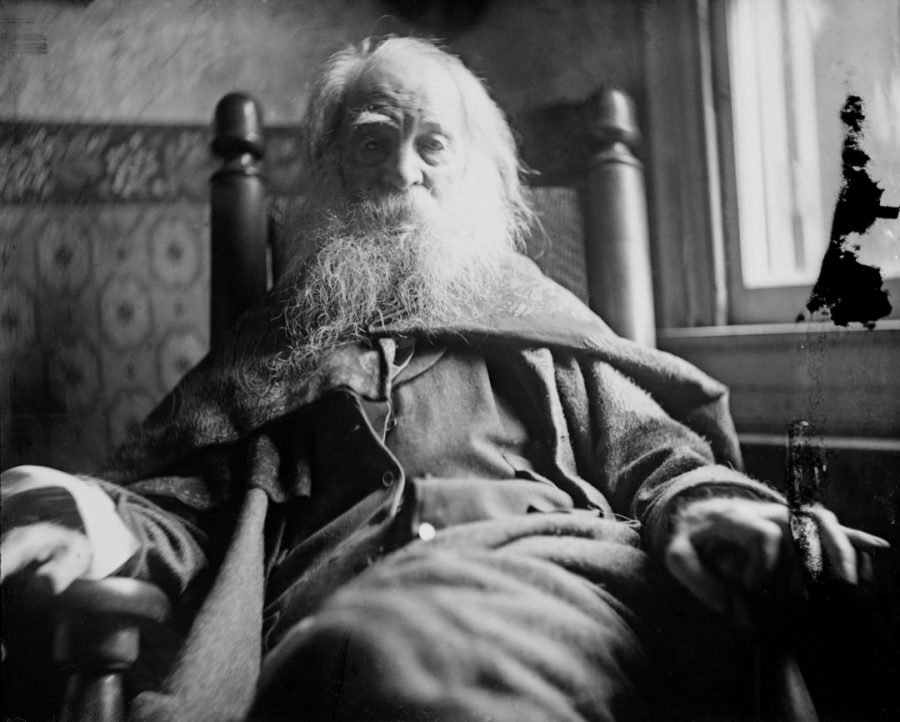

Long before Brandon Stanton’s wildly popular Humans of New York project tapped into the public’s capacity for compassion by combining photos of his subjects with some telling narrative about their lives, educator and sociologist Lewis Wickes Hine was using his camera as a tool to pressure the public into demanding an end to child labor in the United States.

In a time when the US Federal Census reported that one in five children under the age of 16—over 1.75 million—was gainfully employed, Hines traversed the country under the auspices of the National Child Labor Committee, gathering information and making portraits of the underage workers.

His images, made between 1911 and 1916, introduced viewers to young boys breaking up coal in Pennsylvania mines, tiny Louisiana oyster shuckers and Maine sardine cutters, child pickers in Kentucky tobacco fields and Massachusetts cranberry bogs, and newsboys in a number of cities.

Their employers actively recruited kids from poor families, wagering that they would perform repetitive, often dangerous tasks for a pittance, with little chance of unionizing.

Hine was a scrupulous documentarian, labeling each photo with crucial information gleaned from conversations with the child pictured therein: name, age, location, occupation, wages, and—horrifically—any workplace injuries.

In an essay in the anthology Major Problems in the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, historian Robert Westbrook lauds Hines’ way of interacting with his subjects with “decorum and tact,” according them a dignity that few of the period’s “condescending” middle-class reformers did.

As the Vox Darkroom segment, above, explains, Hine’s formal compositions lent additional power to his images of smudged child workers posing in their places of employment. Shallow depth of field to ensure that the viewer’s eyes would not become absorbed in the background, but rather engage with those of his subject.

But it was the accompanying narratives, which he referred to variously as “picture stories” or “photo-interpretations,” that he credited with really getting through to the hearts and minds of an indifferent public.

The text prevented viewers from easily brushing the children off as anonymous, scruffy urchins.

Here for instance is “Manuel, the young shrimp-picker, five years old, and a mountain of child-labor oyster shells behind him. He worked last year. Understands not a word of English. Dunbar, Lopez, Dukate Company. Location: Biloxi, Mississippi.”

“Laura Petty, a 6 year old berry picker on Jenkins farm, Rock Creek near Baltimore, Md. ‘I’m just beginnin.’ Picked two boxes yesterday. (2 cents a box).”

“Angelo Ross, 142 Panama Street, Hughestown Borough, a youngster who has been working in Breaker #9 Pennsylvania Co. for four months, said he was 13 years old, but very doubtful. He has a brother, Tony, probably under 14 working. Location: Pittston, Pennsylvania.”

Hine correctly figured that the combination of photo and biographical information was a “lever for the social uplift.”

Once the pictures were published in Progressive magazines, state legislatures came under immense pressure to impose minimum age requirements in the workplace, effectively ending child labor, and returning many former workers to school.

View the entire collection of Lewis Hine’s National Child Labor Committee photos here.

Related Content:

How Dorothea Lange Shot, Migrant Mother, Perhaps the Most Iconic Photo in American History

Meet Gerda Taro, the First Female Photojournalist to Die on the Front Lines

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC this March, when her company, Theater of the Apes, presents the world premiere of Tony Award winner Greg Kotis’ new low-budget, guitar-driven musical, I AM NOBODY. Follow her @AyunHalliday.