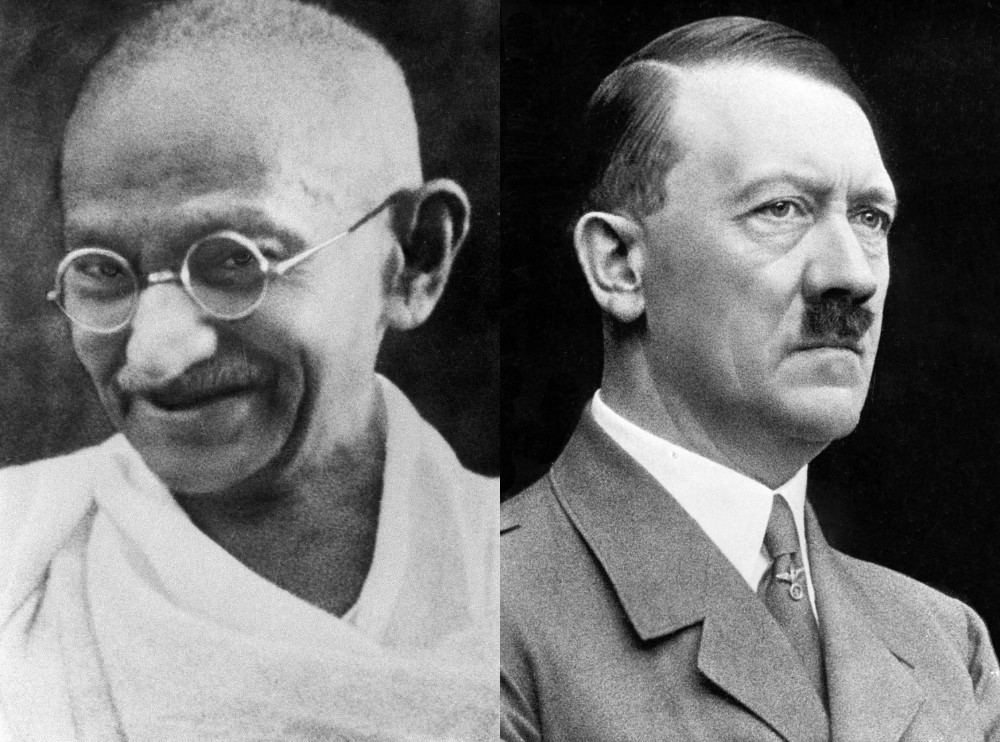

It must come up in every single argument, from sophisticated to sophomoric, about the practicability of non-violent pacifism. “Look what Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. were able to achieve!” “Yes, but what about Hitler? What do you do about the Nazis?” The rebuttal implies future Nazi-like entities looming on the horizon, and though this reductio ad Hitlerum generally has the effect of nullifying any continued rational discussion, it’s difficult to imagine a satisfying pacifist answer to the problem of naked, implacable hatred and aggression on such a scale as that of the Third Reich. Even Gandhi’s own proposal sounds like a joke: in 1940, Adolph Hitler abandons his plans to claim Lebensraum for the German people and to displace, enslave, or eradicate Germany’s neighbors and undesirable citizens. He adopts a posture of non-violence and “universal friendship,” and German forces withdraw from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, France, agreeing to resolve differences through international conference and committee.

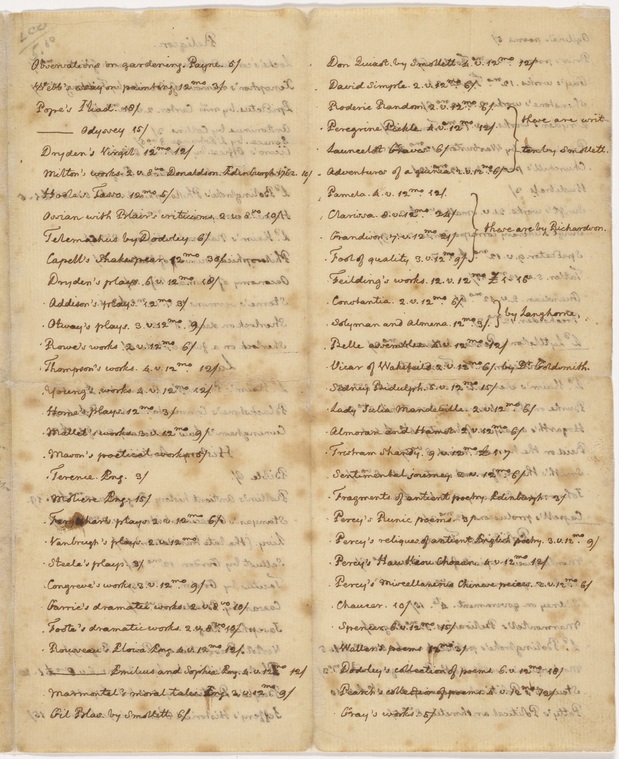

Hitler may have been a vegetarian, but that’s likely where any sympathy between him and Gandhi began and ended. And yet, the above is precisely what Mahatma Gandhi asked of the Fuhrer, in a letter dated December 24, 1940. Engaged fully in the struggle for Indian independence, Gandhi found himself torn by the entry of Britain into the war against Germany. On the one hand, Gandhi initially pledged “nonviolent moral support” for the war, sensing an enemy–Germany–even more threatening to world peace and stability. (That stance would change in short order as the Indian National Congress revolted and resigned en masse rather than participate in the war). On the other hand, Gandhi did not see the British Empire as categorically different from the Nazis. As he put it in his letter to Hitler, whom he addresses as “Friend” (this is “no formality,” he writes, “I own no foes”): “If there is a difference, it is in degree. One-fifth of the human race has been brought under the British heel by means that will not bear scrutiny.”

Gandhi acknowledges the absurdity of his request: “I am aware,” he writes, “that your view of life regards such spoliations as virtuous acts.” And yet, he marshals a formidable argument for nonviolence as a force of power, not weakness, showing how it had weakened British rule: “The movement of independence has been never so strong as now,” he writes, through “the right means to combat the most organized violence in the world which the British power represents”:

It remains to be seen which is the better organized, the German or the British. We know what the British heel means for us and the non-European races of the world. But we would never wish to end the British rule with German aid. We have found in non-violence a force which, if organized, can without doubt match itself against a combination of all the most violent forces in the world. In non-violent technique, as I have said, there is no such thing as defeat. It is all ‘do or die’ without killing or hurting. It can be used practically without money and obviously without the aid of science of destruction which you have brought to such perfection. It is a marvel to me that you do not see that it is nobody’s monopoly. If not the British, some other power will certainly improve upon your method and beat you with your own weapon. You are leaving no legacy to your people of which they would feel proud. They cannot take pride in a recital of cruel deed, however skillfully planned. I, therefore, appeal to you in the name of humanity to stop the war.

As an alternative to war, Gandhi proposes an “international tribunal of your joint choice” to determine “which party was in the right.” His letter, Gandhi writes, should be taken as “a joint appeal to you and Signor Mussolini…. I hope that he will take this as addressed to him also with the necessary changes.”

Gandhi also references an appeal he made “to every Briton to accept my method of non-violent resistance.” That appeal took the form of an open letter he published that July, “To Every Briton,” in which he wrote:

You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions. Let them take possession of your beautiful island, with your many beautiful buildings. You will give all these, but neither your souls, nor your minds. If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourself, man, woman and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them.

When Gandhi visited England that year, he found the viceroy of colonial India “dumbstruck” by these requests, writes Stanley Wolpert in his biography of the Indian leader, “unable to utter a word in response, refusing even to call for his car to take the now more deeply despondent Gandhi home.”

Gandhi’s 1940 letter to Hitler was actually his second addressed to the Nazi leader. The first, a very short missive written in 1939, one month before the ill-fated Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, strikes a conciliatory tone. Gandhi writes that he resisted requests from friends to pen the letter “because of the feeling that any letter from me would be an impertinence,” and though he calls on Hitler to “prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state,” he ends with, “I anticipate your forgiveness, If I have erred in writing to you.” But again, in this very brief letter, Gandhi appeals to the “considerable success” of his nonviolent methods. “There is no evidence,” The Christian Science Monitor remarks, “to suggest Hitler ever responded to either of Gandhi’s letters.”

As the war unavoidably raged, Gandhi redoubled his efforts at Indian independence, launching the “Quit India” movement in 1942, which—writes Open University—“more than anything, united the Indian people against British rule” and hastened its eventual end in 1947. Non-violence succeeded, improbably, against the British Empire, though certain other former colonies won independence through more traditionally warlike methods. And yet, though Gandhi believed non-violent resistance could avert the horrors of World War II, those of us without his level of total commitment to the principle may find it difficult to imagine how it might have succeeded against the Nazis, or how it could have appealed to their totalizing ideology of domination.

Related Content:

Hear Gandhi’s Famous Speech on the Existence of God (1931)

Watch Gandhi Talk in His First Filmed Interview (1947)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness