Watch television creator Allen Funt predict flash mobs in the 1962 episode of Candid Camera above, filmed some forty years before Harper’s magazine editor, Bill Wasik, founded the movement with anonymously e‑mailed instructions for a coordinated public action.

The stunt, entitled “Face the Rear,” was pulled off by a handful of “agents”—a phrase coined by Improv Everywhere’s founder Charlie Todd to describe the poker-faced participants conjuring a secretly agreed upon alternate reality to confound (and not always delight) its target subject, along with unsuspecting bystanders.

Compared to the grand-scale theatrics that have transformed an upscale market into a scene from La Traviata and infiltrate subways worldwide with thousands of pants-less riders every year, this prank is quite subtle in the execution.

It succeeds on our tacit understanding of what constitutes proper elevator behavior when others passengers are present. Left to our own devices, we can sing, dance, and let the mask of propriety slip in any number of ways. Once others enter? We share the space and face forward.

But what if everyone who enters inexplicably faces the back wall?

What would you do?

As hypotheticals go, this one’s not nearly so weighty as considering whether you’d have followed the script of Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments or put your own family at risk by hiding Anne Frank.

Still…

For the subjects of Candid Camera’s elevator gag, the pressure to succumb to group think quickly overruled years of learned physical behavior.

And normative elevator physicality definitely springs from social cues, as John Donovan, host of NPR’s “Around the Nation” said, in an interview with Lee Gray, author of From Ascending Rooms to Express Elevators: A History of the Passenger Elevator in the 19th Century:

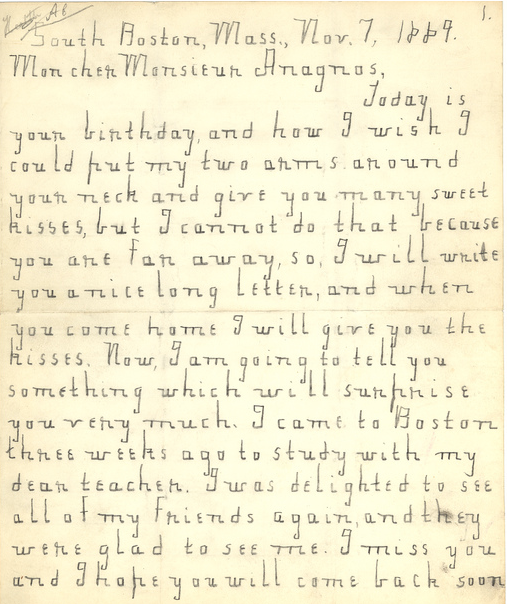

I know a psychologist who works with teenagers who have autism who—he uses encouraging to learn skills that will allow them to be independent in the world to get out on their own. And one of his lessons with some of the teenagers is what to do in an elevator because he says that the typical kid that he works with, when the door is opened, and he’s been told that he should step inside, will step inside and face the back wall because nobody has told him that everybody else in the elevator is going to turn around and face the front doors…

Candid Camera’s stunts were always framed as comedy, though its creator, Funt, was well versed in psychology, having served as child psychologist Kurt Lewin’s research assistant at Cornell University.

In an article for the Archive of American Television, writer Amy Loomis identified five premises into which the average Candid Camera gag could fall:

- Reversing normal or anticipated procedures

- Exposing basic human weaknesses such as ignorance or vanity

- Using the element of surprise

- Fulfilling fantasies

- Placing something in a bizarre or inappropriate setting

“Face the Rear” was a case where conformity born of an unexpected reversal in normal procedure yielded laughs, at the gentle expense of a series of unsuspecting subjects, whose solo rides were disrupted by a bunch of Candid Camera operatives.

Related Content:

This is Your Brain on Sex and Religion: Experiments in Neuroscience

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.