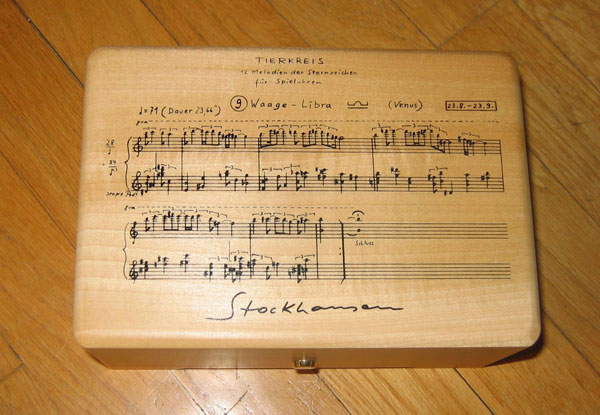

We now remember Karlheinz Stockhausen as a pioneer of electronic music, laboring away in studios dominated by hulking early synthesizers and tape machines toward a new sonic experience, but he wrote his most popular work for much humbler devices: music boxes. Composed in 1974 and 1975, Tierkreis, the German word for zodiac, consists of twelve melodies, each representing a sign on that astrological calendar, each centered on a different pitch, each played on its own dedicated music box. You can hear (and see) all of the Tierkreis boxes in action in these videos:

Despite their simplicity, Stockhausen’s twelve- and sometimes fourteen-tone serial compositions may sound like nothing you ever heard come out of a music box in childhood. But children must have made up a significant part of their early audience: these melodies made their debut as part of the fairy-tale music theater piece called Musik im Bauch, or “Music in the Belly,” a phrase Stockhausen used to describe the noises that would issue from the insides of his young daughter Julika, to her great delight. After coming up with the twelve melodies, quite possibly the first music ever originally composed for the music box, he had to order the boxes themselves custom-made from the Swiss manufacturer Reuge. You can see an original Tierkreis box, playing the Aries melody, in the video below.

Reuge, according to Dangerous Minds’ Oliver Hall, “continued to manufacture the zodiac boxes into the eighties. In ‘98, Stockhausen-Verlag produced a limited run for the composer’s 70th birthday, followed by another series in 2005. The Pisces, Aries and Sagittarius boxes are sold out, but the shop still has a few of the others left at €310 a piece.” Pricey, certainly, but what a gift they would make for musically inclined friends born under the other zodiac signs, given that Stockhausen, writes All Music Guide’s Robert Kirzinger, “carefully considered the characteristics of each sign and each month of the year, as well as the personalities of people he knew were born under a particular sign, in composing this work.” Such a compositional scheme may strike astrological non-believers as odd, but remember: this was back in the age of Aquarius.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.