After the fire that totally destroyed Brazil’s Museu Nacional in Rio, many people lamented that the museum had not digitally backed up its collection and pointed to the event as a tragic example of why such digitization is so necessary. Just a couple decades ago, storing and displaying this much information was impossible, so it may seem like a strange demand to make. And in any case, two-dimensional images stored on servers—or even 3D printed copies—cannot replace or substitute for original, priceless artifacts or works of art.

But museums around the world that have digitized most–or all–of their collections don’t claim to have replicated or replaced the experience of an in-person visit, or to have rendered physical media obsolete.

Digital collections provide access to millions of people who cannot, or will not, ever travel to the major cities in which fine art resides, and they give millions of scholars, teachers, and students resources once available only to a select few.

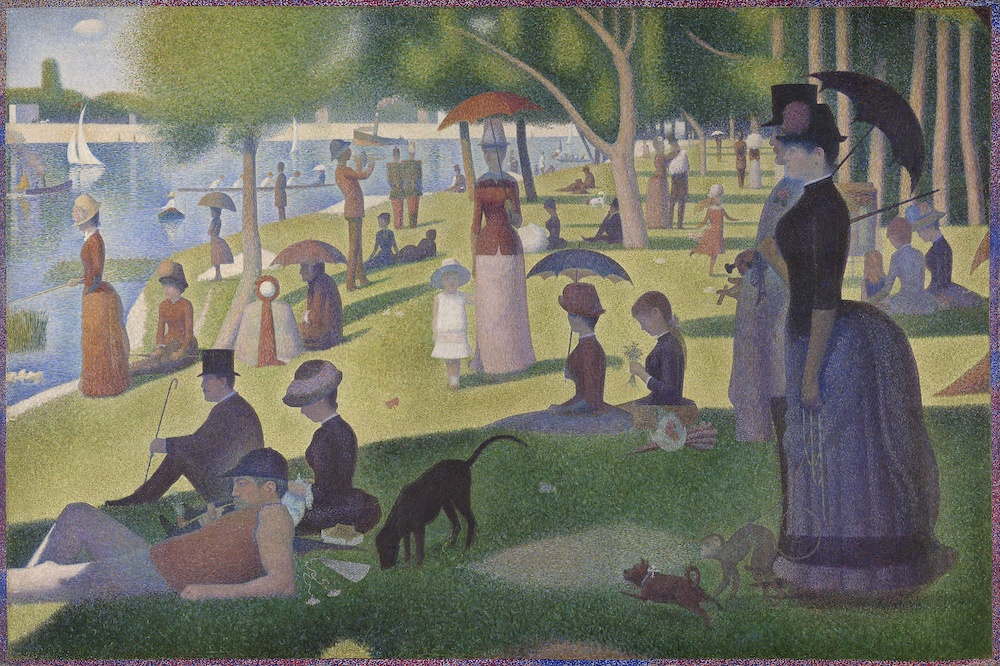

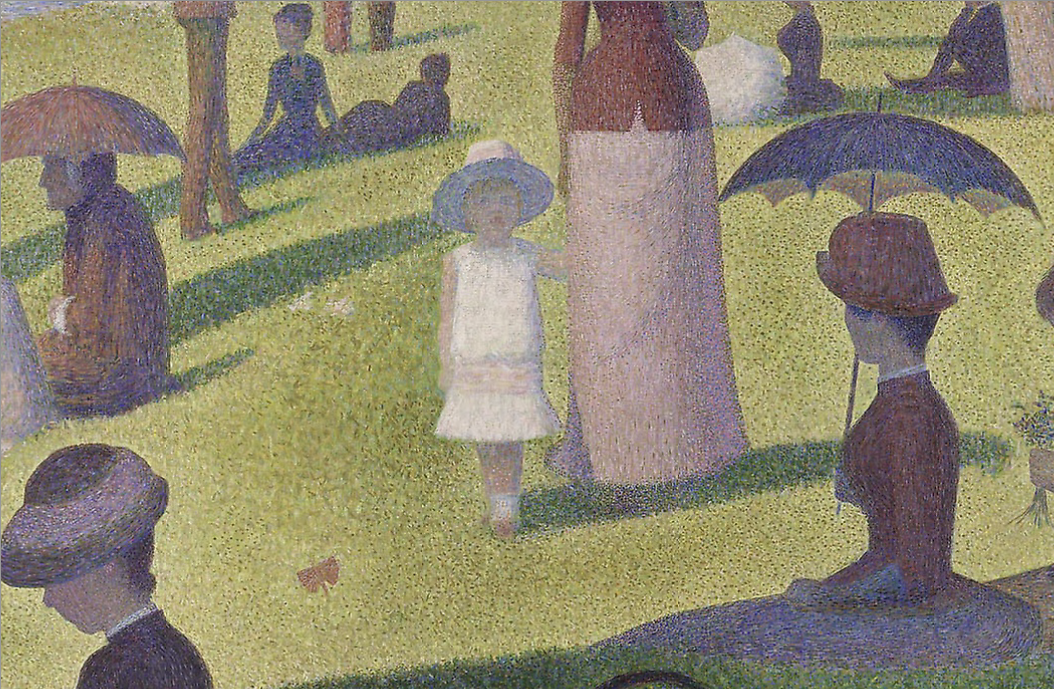

We can’t all take the day off like Ferris Bueller and stand in front of Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. But thanks to the Art Institute of Chicago, we can all view and download the 1884 pointillist painting in high resolution, zoom in closely like the troubled Cameron to specific details, share the digital image under a Creative Commons Zero license, and similarly interact with an oil sketch for the final painting and several conté crayon studies.

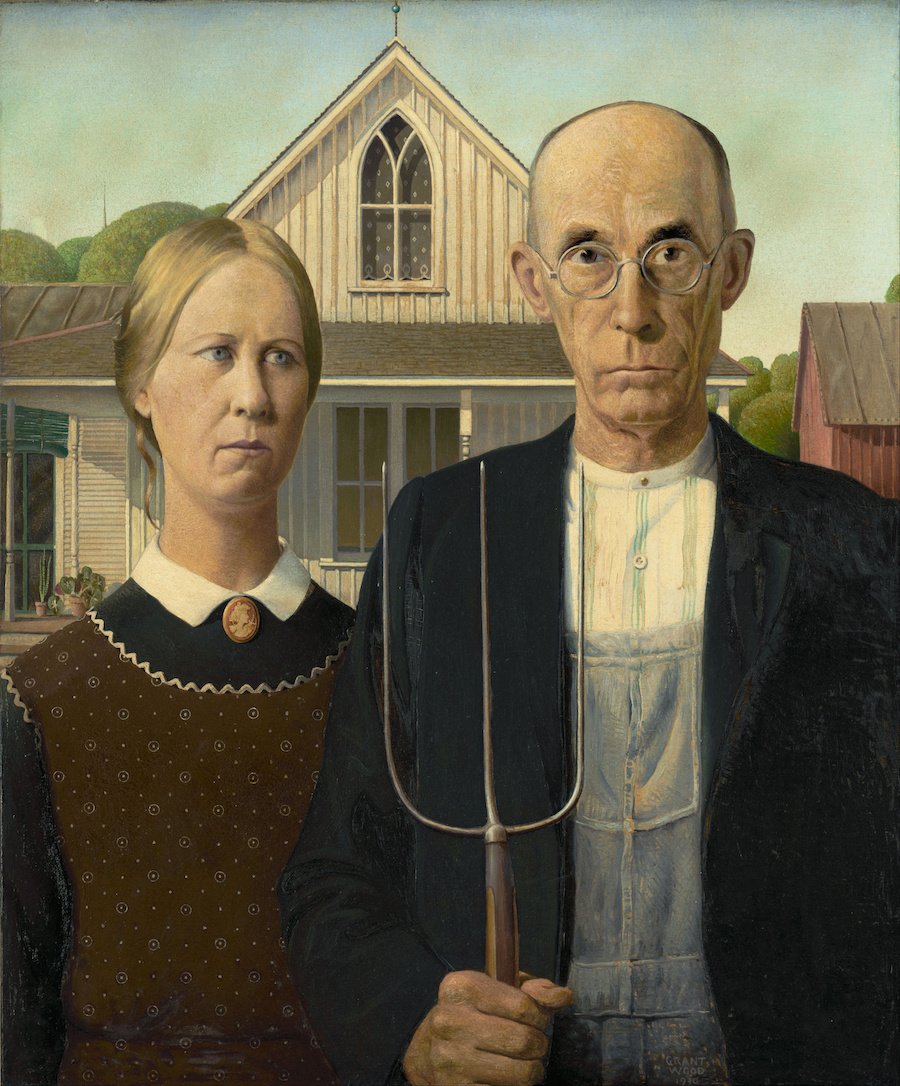

And if that weren’t enough, the museum also includes a bibliography, exhibition history, notes on provenance, audio and video histories and descriptions, and educational resources like teacher manuals, lesson plans, and exams. This goes for many of the 44,312—with more to come—digital images online, including such famous works of art as Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 The Bedroom, Grant Wood’s 1930 American Gothic, Pablo Picasso’s 1903–4 blue period painting The Old Guitarist, Edward Hopper’s 1942 Nighthawks, Mary Cassatt’s 1893 The Child’s Bath, and so many more that it boggles the mind.

Browse Impressionism, Pop Art, works from the African Diaspora, Cityscapes, Fashion, Mythological Works, and other genres and categories. Search artists, dates, styles, media, departments, places, and more.

A personal visit to the Art Institute is an awe-inspiring, and somewhat overwhelming experience, if you can get the day to go. You can visit the website, with full unrestricted access, and gather information, study, marvel, and casually browse, at any time of day—every day if you like. No, it’s not the same, but as a learning experience, in some ways, it’s even better. And if, by some awful chance, anything should happen to this art, we won’t have to rely on user-submitted photos to reconstruct the cultural memory.

The launch of this collection comes as part of the museum’s website redesign, and it is an extensive, and expensive, endeavor. The Art Institute, which charges for entry, can afford to make its collections free online. Some other museums charge image fees to support their online work. Ideally, as art historian Bendor Grosvenor writes at Art History News, museums should offer free and open access to both physical and online collections, and some institutions, like Sweden’s Nationalmuseum, have shown that this is possible.

And, as Grosvenor shows, the success of open access online collections has yielded another benefit, for both viewers and museums alike. The more people are exposed to art online, the more likely they are to visit museums in person. Chicago awaits you. Until then, virtually immerse yourself in the Art Institute’s many thousands of treasures here.

Related Content:

1.8 Million Free Works of Art from World-Class Museums: A Meta List of Great Art Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness