Learn to Become a Digital Marketing Analyst with Unilever’s New Certificate Program

Unilever, the consumer goods company headquartered in London, owns over 400 brands. Dove, Lipton, Ben & Jerry’s, Hellmann’s and Knorr–you know and use many of Unilever’s products. The same goes for many people living across the globe. An estimated 3.4 billion people use Unilever products every day. How has Unilever established such vast reach? Through marketing. Like other consumer products companies, Unilever depends on marketing to build brand awareness for each product and to differentiate them from competitors. Marketing is part of the lifeblood of the organization, and digital marketing particularly allows the company to thrive here in the 21st century.

Happily, for any aspiring marketers out there, Unilever has just launched a new Digital Marketing Analyst certificate program. Offered on the Coursera platform, the program consists of four courses (each taking an estimated 20 hours to complete) that focus on helping students build job-ready skills in digital marketing analytics. The courses include:

- Customer Understanding and Digital Marketing Channels

- Measurement and Analysis

- Campaign Performance Reporting, Visualization, & Improvement

- Advanced Tools for Digital Marketing Analytics

As students move through the program, they will “learn in-demand skills like data analysis, customer segmentation, and SEO optimization.” They will also start “collecting and interpreting data to evaluate the performance of digital marketing efforts, improve strategies, and contribute to achieving marketing goals and objectives.”

Students can audit each course for free, or sign up to earn a shareable certificate. Students who select the latter option will be charged $49 per month. So, if you spend 10 hours per week, you can complete the 80-hour certificate program in two months, and pay about $100 in total.

Sign up for the Digital Marketing Analyst certificate program here.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content

Generative AI for Everyone: A Free Course from AI Pioneer Andrew Ng

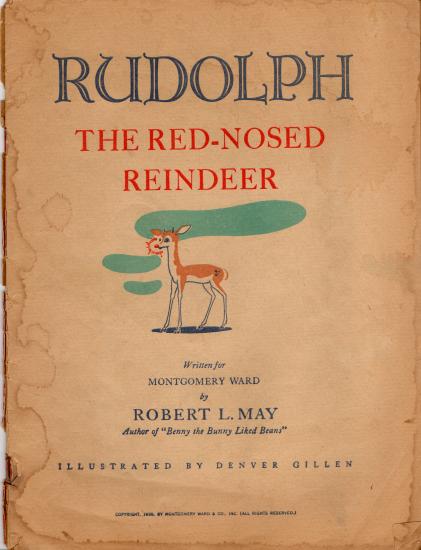

Read More...The Origin Story of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: How a 1939 Marketing Gimmick Launched a Beloved Christmas Character

It’s time to forget nearly everything you know about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer…at least as established by the 1964 Rankin/Bass stop motion animated television special.

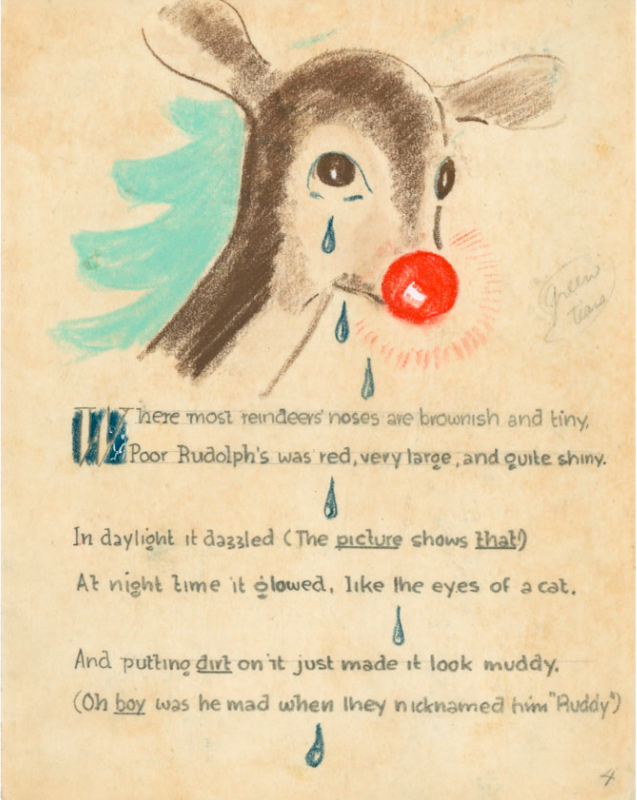

You can hang onto the source of Rudolph’s shame and eventual triumph — the glowing red nose that got him bounced from his playmates’ reindeer games before saving Christmas.

Lose all those other now-iconic elements — the Island of Misfit Toys, long-lashed love interest Clarice, the Abominable Snow Monster of the North, Yukon Cornelius, Sam the Snowman, and Hermey the aspirant dentist elf.

As originally conceived, Rudolph (runner up names: Rollo, Rodney, Roland, Roderick and Reginald) wasn’t even a resident of the North Pole.

He lived with a bunch of other reindeer in an unremarkable house somewhere along Santa’s delivery route.

Santa treated Rudolph’s household as if it were a human address, coming down the chimney with presents while the occupants were asleep in their beds.

To get to Rudolph’s origin story we must travel back in time to January 1939, when a Montgomery Ward department head was already looking for a nationwide holiday promotion to draw customers to its stores during the December holidays.

He settled on a book to be produced in house and given away free of charge to any child accompanying their parent to the store.

Copywriter Robert L. May was charged with coming up with a holiday narrative starring an animal similar to Ferdinand the Bull.

After giving the matter some thought, May tapped Denver Gillen, a pal in Montgomery Ward’s art department, to draw his underdog hero, an appealing-looking young deer with a red nose big enough to guide a sleigh through thick fog.

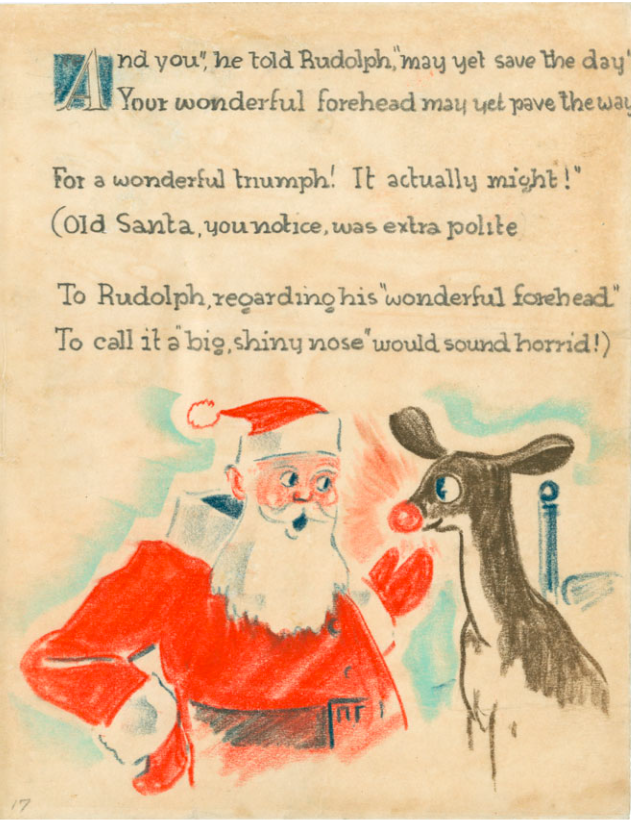

(That schnozz is not without controversy. Prior to Caitlin Flanagan’s 2020 essay in the Atlantic chafing at the television special’s explicitly cruel depictions of othering the oddball, Montgomery Ward fretted that customers would interpret a red nose as drunkenness. In May’s telling, Santa is so uncomfortable bringing up the true nature of the deer’s abnormality, he pretends that Rudolph’s “wonderful forehead” is the necessary headlamp for his sleigh…)

On the strength of Gillen’s sketches, May was given the go-ahead to write the text.

His rhyming couplets weren’t exactly the stuff of great children’s literature. A sampling:

Twas the day before Christmas, and all through the hills,

The reindeer were playing, enjoying the spills.

Of skating and coasting, and climbing the willows,

And hopscotch and leapfrog, protected by pillows.

___

And Santa was right (as he usually is)

The fog was as thick as a soda’s white fizz

—-

The room he came down in was blacker than ink

He went for a chair and then found it a sink!

No matter.

May’s employer wasn’t much concerned with the artfulness of the tale. It was far more interested in its potential as a marketing tool.

“We believe that an exclusive story like this aggressively advertised in our newspaper ads and circulars…can bring every store an incalculable amount of publicity, and, far more important, a tremendous amount of Christmas traffic,” read the announcement that the Retail Sales Department sent to all Montgomery Ward retail store managers on September 1, 1939.

Over 800 stores opted in, ordering 2,365,016 copies at 1½¢ per unit.

Promotional posters touted the 32-page freebie as “the rollickingest, rip-roaringest, riot-provokingest, Christmas give-away your town has ever seen!”

The advertising manager of Iowa’s Clinton Herald formally apologized for the paper’s failure to cover the Rudolph phenomenon — its local Montgomery Ward branch had opted out of the promotion and there was a sense that any story it ran might indeed create a riot on the sales floor.

His letter is just but one piece of Rudolph-related ephemera preserved in a 54-page scrapbook that is now part of the Robert Lewis May Collection at Dartmouth, May’s alma mater.

Another page boasts a letter from a boy named Robert Rosenbaum, who wrote to thank Montgomery Ward for his copy:

I enjoyed the book very much. My sister could not read it so I read it to her. The man that wrote it done better than I could in all my born days, and that’s nine years.

The magic ingredient that transformed a marketing scheme into an evergreen if not universally beloved Christmas tradition is a song …with an unexpected side order of corporate generosity.

May’s wife died of cancer when he was working on Rudolph, leaving him a single parent with a pile of medical bills. After Montgomery Ward repeated the Rudolph promotion in 1946, distributing an additional 3,600,000 copies, its Board of Directors voted to ease his burden by granting him the copyright to his creation.

Once he held the reins to the “most famous reindeer of all”, May enlisted his songwriter brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, to adapt Rudolph’s story.

The simple lyrics, made famous by singing cowboy Gene Autry’s 1949 hit recording, provided May with a revenue stream and Rankin/Bass with a skeletal outline for its 1964 stop-animation special.

Screenwriter Romeo Muller, the driving force behind the Island of Misfit Toys, Sam the Snowman, Clarice, et al revealed that he would have based his teleplay on May’s original book, had he been able to find a copy.

Read a close-to-final draft of Robert L. May’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, illustrated by Denver Gillen here.

Bonus content: Max Fleischer’s animated Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer from 1948, which preserves some of May’s original text.

Related Content

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just Like Charles Dickens Read It

Hear Paul McCartney’s Experimental Christmas Mixtape: A Rare & Forgotten Recording from 1965

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...

Google Unveils a Digital Marketing & E‑Commerce Certificate: 7 Courses Will Help Prepare Students for an Entry-Level Job in 6 Months

During the pandemic, Google launched a series of Career Certificates that will “prepare learners for an entry-level role in under six months.” Their first certificates focused on Project Management, Data Analytics, User Experience (UX) Design, IT Support and IT Automation. Now comes their latest–a certificate dedicated to Digital Marketing & E‑commerce.

Offered on the Coursera platform, the Digital Marketing & E‑commerce Professional Certificate consists of seven courses, all collectively designed to help students “develop digital marketing and e‑commerce strategies; attract and engage customers through digital marketing channels like search and email; measure marketing analytics and share insights; build e‑commerce stores, analyze e‑commerce performance, and build customer loyalty.” The courses include:

- Foundations of Digital Marketing and E‑commerce

- Attract and Engage Customers with Digital Marketing

- From Likes to Leads: Interact with Customers Online

- Think Outside the Inbox: Email Marketing

- Assess for Success: Marketing Analytics and Measurement

- Make the Sale: Build, Launch, and Manage E‑commerce Stores

- Satisfaction Guaranteed: Develop Customer Loyalty Online

In total, this program “includes over 190 hours of instruction and practice-based assessments, which simulate real-world digital marketing and e‑commerce scenarios that are critical for success in the workplace.” Along the way, students will learn how to use tools and platforms like Canva, Constant Contact, Google Ads, Google Analytics, Hootsuite, HubSpot, Mailchimp, Shopify, and Twitter. You can start a 7‑day free trial and explore the courses. If you continue beyond that, Google/Coursera will charge $39 USD per month. That translates to about $235 after 6 months.

If you don’t want to pay, you can audit each course for free, without ultimately receiving the certificate.

Explore the Digital Marketing & E‑commerce Professional Certificate.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Coursera. If readers enroll in certain Coursera courses and programs, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content

Read More...When Movies Came on Vinyl: The Early-80s Engineering Marvel and Marketing Disaster That Was RCA’s SelectaVision

Anyone over 30 remembers a time when it was impossible to imagine home video without physical media. But anyone over 50 remembers a time when it was difficult to choose which kind of media to bet on. Just as the “computer zoo” of the early 1980s forced home-computing enthusiasts to choose between Apple, IBM, Commodore, Texas Instruments, and a host of other brands, each with its own technological specifications, the market for home-video hardware presented several different alternatives. You’ve heard of Sony’s Betamax, for example, which has been a punchline ever since it lost out to JVC’s VHS. But that was just the realm of video tape; have you ever watched a movie on a vinyl record?

Four decades ago, it was difficult for most consumers to imagine home video at all. “Get records that let you have John Travolta dancing on your floor, Gene Hackman driving though your living room, the Godfather staying at your house,” booms the narrator of the television commercial above.

How, you ask? By purchasing a SelectaVision player and compatible video discs, which allow you to “see the entertainment you really want, when you want, uninterrupted.” In our age of streaming-on-demand this sounds like a laughably pedestrian claim, but at the time it represented the culmination of seventeen years and $600 million of intensive research and development at the Radio Company of America, better known as RCA.

Radio, and even more so its successor television, made RCA an enormous (and enormously profitable) conglomerate in the first half of the twentieth century. By the 1960s, it commanded the resources to work seriously on such projects as a vinyl record that could contain not just music, but full motion pictures in color and stereo. This turned out to be even harder than it sounded: after numerous delays, RCA could only bring SelectaVision to market in the spring of 1981, four years after the internal target. By that time, after the company had been commissioning content for the better part of a decade (D. A. Pennebaker shot David Bowie’s final Ziggy Stardust concert in 1973 on commission from RCA, who’d intended to make a SelectaVision disc out of it), the format faced competition from not just VHS and Betamax but the cutting-edge LaserDisc as well.

Nevertheless, the SelectaVision’s ultra-densely encoded vinyl video discs — officially known as capacitance electronic discs, or CEDs — were, in their way, marvels of engineering. You can take a deep dive into exactly what makes the system so impressive, which involves not just a breakdown of its components but a complete retelling of the history of RCA, though the five-part Technology Connections miniseries at the top of the post. True completists can also watch RCA’s video tour of its SelectaVision production facilities, as well as its live dealer-introduction broadcast hosted by Tom Brokaw and featuring a Broadway-style musical number. SelectaVision was also rolled out in the United Kingdom in 1983, thus qualifying for a hands-on examination by British retro-tech Youtuber Techmoan.

SelectaVision lasted just three years. Its failure was perhaps overdetermined, and not just by the bad timing resulting from its troubled development. In the early 1980s, the idea of buying pre-recorded video media lacked the immediate appeal of “time-shifting” television, which had become possible only with video tape. Nor did RCA, whose marketing centered on the possibility of building a permanent home-video library in the manner of one’s music library, foresee the possibility of rental. And though CEDs were ultimately made functional, they remained cumbersome, able to hold just one hour of video per side and notoriously subject to jitters even on the first play. Yet as RCA’s ad campaigns emphasized, there really was a “magic” in being able to watch the movies you wanted at home, whenever you wanted to. In that sense, at least, we now live in a magical world indeed.

Related content:

The Story of the MiniDisc, Sony’s 1990s Audio Format That’s Gone But Not Forgotten

A Celebration of Retro Media: Vinyl, Cassettes, VHS, and Polaroid Too

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Take 193 Free Tech and Business Courses Online at Udacity: Product Design, Programming, A.I., Marketing & More

Each of us now commands more technological power than did any human being alive in previous eras. Or rather, we potentially command it: what we can do with the technology at our fingertips — and how much money we can make with it — depends on how well we understand it. Luckily, the development of learning methods has more or less kept pace with the development of everything else we now do with computers. Take the online-education platform Udacity, which offers “nanodegree” programs in areas like programming, data science, and cybersecurity. While the nanodegrees themselves come with fees, Udacity doesn’t charge for the constituent courses: in other words, you can earn what you need to know for free.

Above you’ll find the introduction to Udacity’s Product Design course by Google (also creator of the Coursera professional-certificate programs previously featured here on Open Culture). “Designed to help you materialize your game-changing idea and transform it into a product that you can build a business around,” the course “blends theory and practice to teach you product validation, UI/UX practices, Google’s Design Sprint and the process for setting and tracking actionable metrics.”

This is a highly practical learning experience at the intersection of technology and business, as are many other of Udacity’s 193 free courses, like App Marketing, App Monetization, How to Build a Startup, and Get Your Startup Started.

If you have no particular interest in founding and running the next Google, Udacity also hosts plenty of courses that focus entirely on the workings of different branches of technology, from programming and artificial intelligence to 2D game development and 3D graphics. (In addition to the broad introductions, there are also relatively advanced courses of a much more specific focus: Developing Android Apps with Kotlin, say, or Deploying a Hadoop Cluster.) And if you’d simply like to get your foot in the door with a job in tech, consider such offerings as Refresh Your Résumé, Strengthen Your LinkedIn Network & Brand, and a variety of interview-preparation courses for jobs in data science, machine learning, product management, virtual-reality development, and other subfields. And however cutting-edge their work, who couldn’t another spin through good old Intro to Psychology?

Find a list of 193 Free Udacity courses here. For the next week Nanodegrees are 75% off (use code JULY75). Find more free courses in our list, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Note: Open Culture has a partnership with Udacity. If readers enroll in certain Udacity courses and programs that charge a fee, it helps support Open Culture.

Related Content:

Learn How to Code for Free: A DIY Guide for Learning HTML, Python, Javascript & More

1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...An Introduction to Consumer Neuroscience & Neuromarketing: A Free Online Course from the University of Copenhagen

Thomas Zoëga Ramsøy, a neuropsychologist at the University of Copenhagen, presents An Introduction to Consumer Neuroscience & Neuromarketing, a course that explores the following set of questions:

How do we make decisions as consumers? What do we pay attention to, and how do our initial responses predict our final choices? To what extent are these processes unconscious and cannot be reflected in overt reports? This course will provide you with an introduction to some of the most basic methods in the emerging fields of consumer neuroscience and neuromarketing. You will learn about the methods employed and what they mean. You will learn about the basic brain mechanisms in consumer choice, and how to stay updated on these topics. The course will give an overview of the current and future uses of neuroscience in business.

You can take Introduction to Consumer Neuroscience & Neuromarketing for free by selecting the audit option upon enrolling. If you want to take the course for a certificate, you will need to pay a fee.

Introduction to Consumer Neuroscience & Neuromarketing will be added to our list of Free Business Courses, a subset of our collection: 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

For a complete list of online courses, please visit our complete collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

For a list of online certificate programs, visit 200 Online Certificate & Microcredential Programs from Leading Universities & Companies, which features programs from our partners Coursera, Udacity, FutureLearn and edX.

And if you’re interested in Online Mini-Masters and Master’s Degrees programs from universities, see our collection: Online Degrees & Mini Degrees: Explore Masters, Mini Masters, Bachelors & Mini Bachelors from Top Universities.

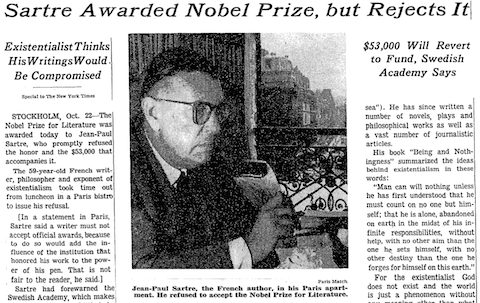

Read More...Jean-Paul Sartre Rejects the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964: “It Was Monstrous!”

In a 2013 blog post, the great Ursula K. Le Guin quotes a London Times Literary Supplement column by a “J.C.,” who satirically proposes the “Jean-Paul Sartre Prize for Prize Refusal.” “Writers all over Europe and America are turning down awards in the hope of being nominated for a Sartre,” writes J.C., “The Sartre Prize itself has never been refused.” Sartre earned the honor of his own prize for prize refusal by turning down the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, an act Le Guin calls “characteristic of the gnarly and counter-suggestible Existentialist.” As you can see in the short clip above, Sartre fully believed the committee used the award to whitewash his Communist political views and activism.

But the refusal was not a theatrical or “impulsive gesture,” Sartre wrote in a statement to the Swedish press, which was later published in Le Monde. It was consistent with his longstanding principles. “I have always declined official honors,” he said, and referred to his rejection of the Legion of Honor in 1945 for similar reasons. Elaborating, he cited first the “personal” reason for his refusal

This attitude is based on my conception of the writer’s enterprise. A writer who adopts political, social, or literary positions must act only with the means that are his own—that is, the written word. All the honors he may receive expose his readers to a pressure I do not consider desirable. If I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre it is not the same thing as if I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre, Nobel Prize winner.

The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honorable circumstances, as in the present case.

There was another reason as well, an “objective” one, Sartre wrote. In serving the cause of socialism, he hoped to bring about “the peaceful coexistence of the two cultures, that of the East and the West.” (He refers not only to Asia as “the East,” but also to “the Eastern bloc.”)

Therefore, he felt he must remain independent of institutions on either side: “I should thus be quite as unable to accept, for example, the Lenin Prize, if someone wanted to give it to me.”

As a flattering New York Times article noted at the time, this was not the first time a writer had refused the Nobel. In 1926, George Bernard Shaw turned down the prize money, offended by the extravagant cash award, which he felt was unnecessary since he already had “sufficient money for my needs.” Shaw later relented, donating the money for English translations of Swedish literature. Boris Pasternak also refused the award, in 1958, but this was under extreme duress. “If he’d tried to go accept it,” Le Guin writes, “the Soviet Government would have promptly, enthusiastically arrested him and sent him to eternal silence in a gulag in Siberia.”

These qualifications make Sartre the only author to ever outright and voluntarily reject both the Nobel Prize in Literature and its sizable cash award. While his statement to the Swedish press is filled with polite explanations and gracious demurrals, his filmed statement above, excerpted from the 1976 documentary Sartre by Himself, minces no words.

Because I was politically involved the bourgeois establishment wanted to cover up my “past errors.” Now there’s an admission! And so they gave me the Nobel Prize. They “pardoned” me and said I deserved it. It was monstrous!

Sartre was in fact pardoned by De Gaulle four years after his Nobel rejection for his participation in the 1968 uprisings. “You don’t arrest Voltaire,” the French President supposedly said. The writer and philosopher, Le Guin points out, “was, of course, already an ‘institution’” at the time of the Nobel award. Nonetheless, she says, the gesture had real meaning. Literary awards, writes Le Guin—who herself refused a Nebula Award in 1976 (she’s won several more since)—can “honor a writer,” in which case they have “genuine value.” Yet prizes are also awarded “as a marketing ploy by corporate capitalism, and sometimes as a political gimmick by the awarders [….] And the more prestigious and valued the prize the more compromised it is.” Sartre, of course, felt the same—the greater the honor, the more likely his work would be coopted and sanitized.

Perhaps proving his point, a short, nasty 1965 Harvard Crimson letter had many, less flattering things than Le Guin to say about Sartre’s motivations, calling him “an ugly toad” and a “poor loser” envious of his former friend Camus, who won in 1957. The letter writer calls Sartre’s rejection of the prize “an act of pretension” and a “rather ineffectual and stupid gesture.” And yet it did have an effect. It seems clear at least to me that the Harvard Crimson writer could not stand the fact that, offered the “most coveted award” the West can bestow, and a heaping sum of money besides, “Sartre’s big line was, ‘Je refuse.’”

Related Content:

Jean-Paul Sartre & Albert Camus: Their Friendship and the Bitter Feud That Ended It

Hear Albert Camus Deliver His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech (1957)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Las Vegas’ Sphere Actually Works: A Looks Inside the New $2.3 Billion Arena

If the United States of America is the Roman empire of our time, surely it must have an equivalent of the Colosseum. A year ago, you could’ve heard a wide variety of speculations as to what structure that could possibly be. Today, many of us would simply respond with “the Sphere,” especially if we happen to be think-piece writers. Since it opened last September, Sphere — to use its proper, article-free brand name — has inspired more than a few reflections on what it says about the intersection of technology and culture here in the twenty-first century, not to mention the considerable ambition and expense of its design and construction.

A $2.3 billion dome whose interior and exterior are both enormous screens — visible, one often hears, even from outer space — Sphere would hardly make sense anywhere in America but Las Vegas, where it makes a good deal of sense indeed. Its location has also made possible such irresistible headlines as “Sphere and Loathing in Las Vegas,” below which the Atlantic’s Charlie Warzel gets into the details of this “architectural embodiment of ridiculousness,” including its surprising origin: “According to James Dolan, the entertainment mogul who financed the Sphere, the inspiration for the building came from ‘The Veldt,’ a 1950 short story by Ray Bradbury” involving a family house with giant screens for walls that can render whatever the children imagine.

Naturally, the kids get hooked, and when Mom and Dad try to intervene, the screens send forth a pack of lions to eat them. “Though the Sphere’s marketing pitch doesn’t explicitly mention being mauled by big digital cats,” Warzel writes, “I got the notion that at least part of the allure of coming to the Sphere is a desire to be overwhelmed.” How, exactly, the venue marshals its advanced technology to do that overwhelming is explained in the MegaBuilds video at the top of the post. With its form not quite like any event space built in human history, it necessitated the invention of everything from a custom camera system to audio-permeable screen surfaces, none of which came cheap.

Hence the cost of seeing a show at Sphere, whether it be the Darren Aronofsky’s “docu-film” Postcard from Earth, U2’s Achtung Baby-based residency earlier this year, or the now-showing Dead & Company, which revives not just the Grateful Dead in their various incarnations over the decades, but also the storied venues in which they played. Its viewers could hardly fail to be astonished by the sheer spectacle, even if they know nothing of the Dead’s colorful history. All of them will no doubt be moved to consider history itself: that of humanity, technology, and civilization, all of which has led up to this rare thing Warzel calls “a brand-new, non-pharmaceutical sensory experience.” Say what you will about the overstimulation and excess represented by Sphere; if you can blow a Deadhead’s mind, you’re definitely on to something.

Related content:

The Absurd Logistics of Concert Tours: The Behind-the-Scenes Preparation You Don’t Get to See

A Virtual Tour of Japan’s Inflatable Concert Hall

Stream a Massive Archive of Grateful Dead Concerts from 1965–1995

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Wes Anderson Directs & Stars in an Ad Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Montblanc’s Signature Pen

One hardly has to be an expert on the films of Wes Anderson to imagine that the man writes with a fountain pen. Maybe back in the early nineteen-nineties, when he was shooting the black-and-white short that would become Bottle Rocket on the streets of Austin, he had to settle for ordinary ballpoints. But now that he’s long since claimed his place in the top ranks of major American auteurs, he can indulge his taste for painstaking craftsmanship and recent-past antiquarianism both onscreen and off. For a brand like Montblanc, this surely made him the ideal choice to direct a commercial celebrating the hundredth anniversary of their flagship writing tool, the Meisterstück.

Shot at Studio Babelsberg in Germany, where Anderson is at work on his next feature The Phoenician Scheme, the resulting short “features Anderson himself, sporting a wispy walrus mustache, as well as frequent collaborators Jason Schwartzman and Rupert Friend, all posing as a group of mountain-climbers with a particular affection for the freedom and inspiration offered by Montblanc’s products,” writes Indiewire’s Harrison Richlin.

Within its first minute, “the ad takes us from the cold, snowy caps of Mont Blanc to a cozy chalet Anderson announces as The Mont Blanc Observatory and Writer’s Room.” Vogue Business’ Christina Binkley reports that this indoor-to-outdoor transition alone required 50 takes, which was only one of the surprises in store for Montblanc’s marketing officer.

Anderson also turned up with an unexpected proposal of his own. “The filmmaker presented a prototype pen of his own design that he asked the German company to manufacture,” Binkley writes. “He’d even named it: the Schreiberling, which means ‘the scribbler’ in German. That had not been part of the pitch.” Perhaps convinced by the built prototype assembled by Anderson’s set-design team, Montblanc “agreed to produce 1,969 copies of this small, green fountain pen to commemorate Anderson’s birth year, 1969.” At 55 years of age, Anderson may no longer be the preternaturally confident young filmmaker we remember from the days of Rushmore or The Royal Tenenbaums, but since then, he’s only grown more adept at getting exactly what he wants from a company, whether it be a movie studio or a European luxury-goods manufacturer.

Related Content:

Wes Anderson’s Shorts Films & Commercials: A Playlist of 8 Short Andersonian Works

Montblanc Unveils a New Line of Miles Davis Pens … and (Kind of) Blue Ink

Why Do Wes Anderson Movies Look Like That?

Has Wes Anderson Sold Out? Can He Sell Out? Critics Take Up the Debate

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

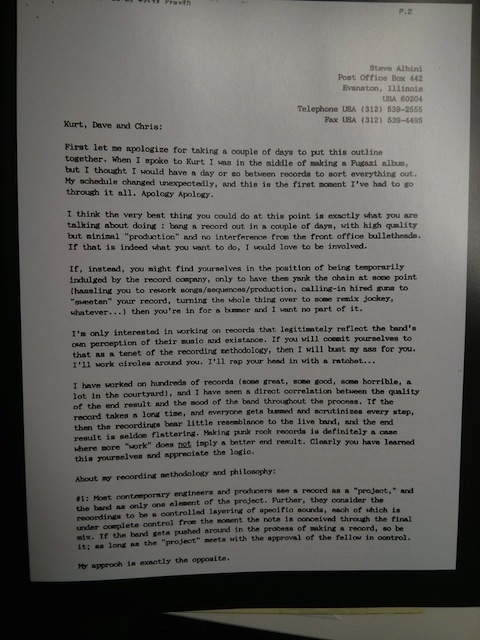

Read More...Read the Uncompromising Letter That Steve Albini (RIP) Wrote to Nirvana Before Producing In Utero (1993)

Today, Steve Albini, the musician and producer of important albums by Nirvana, PJ Harvey, the Pixies and many others, passed away in Chicago, at the all-too-early age of 61. In tribute, we’re bringing you this classic 2013 post from our archive.

Journeyman record producer Steve Albini (he prefers to be called a “recording engineer”) is perhaps the crankiest man in rock. This is not an effect of age. He’s always been that way, since the emergence of his scary, no-frills post-punk band Big Black and later projects Rapeman and Shellac. In his current role as elder statesman of indie rock and more, Chicago’s Albini has developed a reputation as kind of a hardass. He’s also a consummate professional who musicians want to know and work with. From the sound of the Pixies’ Surfer Rosa to Joanna Newsom’s Ys, Albini has had a hand in some of the defining albums of the last thirty plus years, and there is good reason for that: nothing sounds like an Albini record. His method is all his own, and his results—minimalist, dynamic, and raw—are impossible to argue with.

So when Nirvana embarked on recording their final, painful (in hindsight) album In Utero, they asked Albini to steer them away from the more major-label sound of the breakout Nevermind, produced by Butch Vig. True to form, the typically verbose Albini sent a four-page typed letter in response. The letter (first page above—see the rest here) is a testament to perhaps the most thoughtful producer since Quincy Jones and lays out Albini’s philosophy in very fine detail. Two sample paragraphs serve as a thesis:

I’m only interested in working on records that legitimately reflect the band’s own perception of their music and existence. If you will commit yourselves to that as a tenet of the recording methodology, then I will bust my ass for you. I’ll work circles around you. I’ll rap your head with a ratchet…

I have worked on hundreds of records (some great, some good, some horrible, a lot in the courtyard), and I have seen a direct correlation between the quality of the end result and the mood of the band throughout the process. If the record takes a long time, and everyone gets bummed and scrutinizes every step, then the recordings bear little resemblance to the live band, and the end result is seldom flattering. Making punk records is definitely a case where more “work” does not imply a better end result. Clearly you have learned this yourselves and appreciate the logic.

Albini decries any interference from the “front office bulletheads,” or record company execs (his feuds with such people are legendary), and makes it quite clear that he’s there to serve the interests of the band and their sound, not the product of a marketing campaign. While Albini has issued many a surly manifesto over the years, this statement of his craft is maybe the most comprehensive. He is driven by what he calls a “kinship” with the bands he works with. And his passionate commitment to musicians and to quality sound makes him one of the most artistically virtuous people working in popular music today. For more on In Utero, read Dave Grohl’s Rolling Stone interview here. Below, see Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic and Steve Albini discuss the now-famous letter to Nirvana.

Related Content:

Visit “Mariobatalivoice,” the Cooking Blog by Steve Albini, Musician & Record Producer

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...