Since the J. Paul Getty Museum launched its Open Content program back in 2013, we’ve been featuring their efforts to make their vast collection of cultural artifacts freely accessible online. They’ve released not just digitized works of art, but also a great many art history texts and art books in general. Just this week, they announced an expansion of access to their digital archive, in that they’ve made nearly 88,000 images free to download on their Open Content database under Creative Commons Zero (CC0). That means “you can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.”

The Getty suggests that you “add a print of your favorite Dutch still life to your gallery wall or create a shower curtain using the Irises by Van Gogh.” But if you search the open content in their archive yourself, you can surely get much more creative than that.

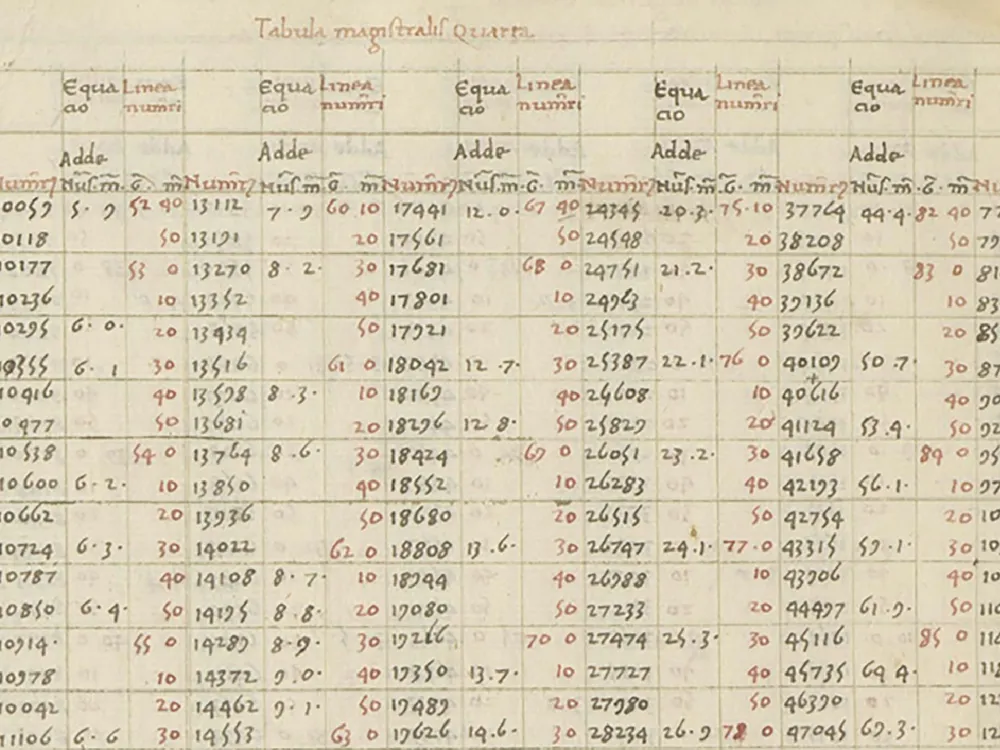

The portal’s interface lets you search by creation date (with a timeline graph stretching back to the year 6000 BC), medium (from agate and alabaster to woodcut and zinc), object type (including paintings, photographs, and sculptures, of course, but also akroteria, horse trappings, and tweezers), and culture. The selection reflects the wide mandate of the Getty’s collection, which encompasses as many of the civilizations of the world as it does the eras of human history.

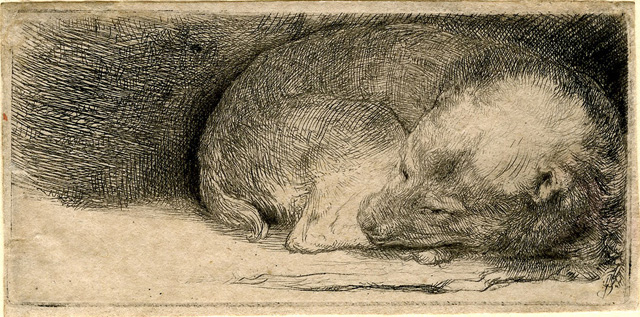

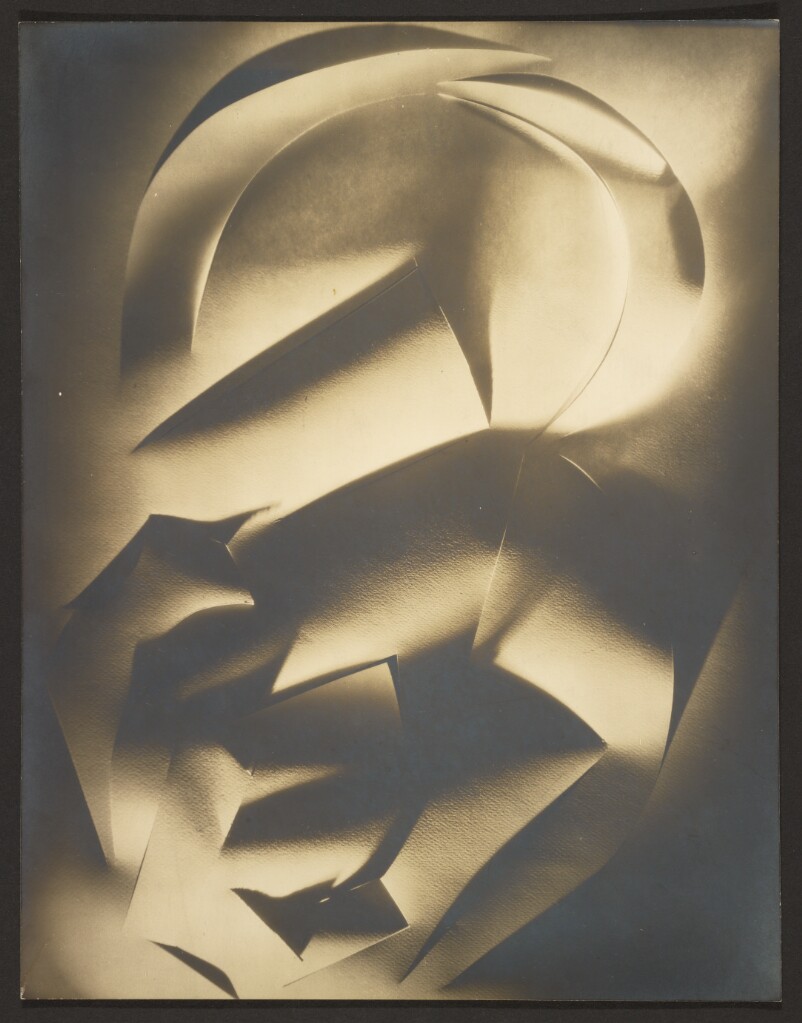

In the Getty’s open-content archive, you’ll find ancient sculpture from Greece, Rome and many other parts of the world besides; a fragmentary oinochoe (that is, a wine jug) from third-century-BC Ptolemaic Egypt; lavishly illuminated medieval books of hours (of the kind previously featured here on Open Culture); works by such innovative French painters as Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas; the stereoscopic photography of Carleton H. Graves, who in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century captured places from Denmark and Palestine, to Japan and Korea; the daring abstractions of artists like Hannes Maria Flach, Jaromír Funke, and Francis Bruguière. But what you do with them is, of course, entirely up to you. Enter the collection here.

Related content:

A Search Engine for Finding Free, Public Domain Images from World-Class Museums

100,000 Free Art History Texts Now Available Online Thanks to the Getty Research Portal

Download Great Works of Art from 40+ Museums Worldwide: Explore Artvee, the New Art Search Engine

Download Over 325 Free Art Books From the Getty Museum

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.