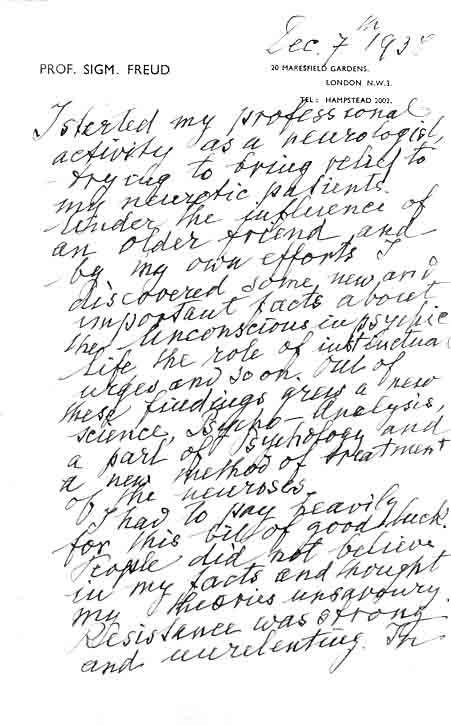

The Walrus is… Dolly Parton?

Not every record yields gold when played backwards or spun more slowly than recommended, but a 45 of Parton’s 1973 hit “Jolene” played at 33RPM not only sounds wonderful, it also manages to reframe the narrative.

As Andrea DenHoed notes in The New Yorker, “Slow Ass Jolene,” above, transforms Parton’s “baby-high soprano” into something deep, soulful and seemingly, male.

In its original version, the much-covered “Jolene” is a straight up woman-to-woman chest-baring. Our narrator knows her man is obsessed with the sexy, auburn-haired Jolene, to the point where he talks about her in his sleep.

Apparently she also knows better than to raise the subject with him. Instead, she appeals to Jolene’s sense of mercy:

You could have your choice of men

But I could never love again

He’s the only one for me, Jolene

The song is somewhat autobiographical, though the situation was nowhere near as dire as listeners might assume. In an interview with NPR, Parton recalled a red-haired bank teller who developed a big crush on her husband when she was a young bride:

And he just loved going to the bank because she paid him so much attention. It was kinda like a running joke between us — when I was saying, ‘Hell, you’re spending a lot of time at the bank. I don’t believe we’ve got that kind of money.’ So it’s really an innocent song all around, but sounds like a dreadful one.

For the record, the teller’s name wasn’t Jolene.

Jolene was a pretty little girl who attended an early Parton concert. Parton was so taken with the child, and her unusual name, that she resolved to write a song about her.

Yes, the kid had red hair and green eyes.

Wouldn’t it be wild if she grew up to be a bank teller?

I digress…

In the original version, the irresistible chorus wherein the soon-to-be-spurned party invokes Jolene’s name again and again is plaintive and fierce.

In the slow ass version, it’s plaintive and sad.

The pain is the same, but the situation in much less straightforward, thanks to blurrier gender lines.

Parton told NPR that women are “always threatened by other women, period.”

Jolene’s prodigious feminine assets could also prove worrisome to a gay man whose bisexual lover’s eye is prone to wander.

Or maybe the singer and his man live in a place where same sex unions are frowned on. Perhaps the singer’s man craves the comfort of a more socially acceptable domestic situation.

Or perhaps Jolene is one hot female-identified tomato, and as far as the singer’s man’s concerned, his pastor and his granny can go to hell! Jolene’s the only one for him.

Or, as one waggish Youtube commenter succinctly put it, “Jolene better stay the hell away from Roy Orbison’s man!”

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

I’m begging of you please don’t take my man

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

Please don’t take him just because you can

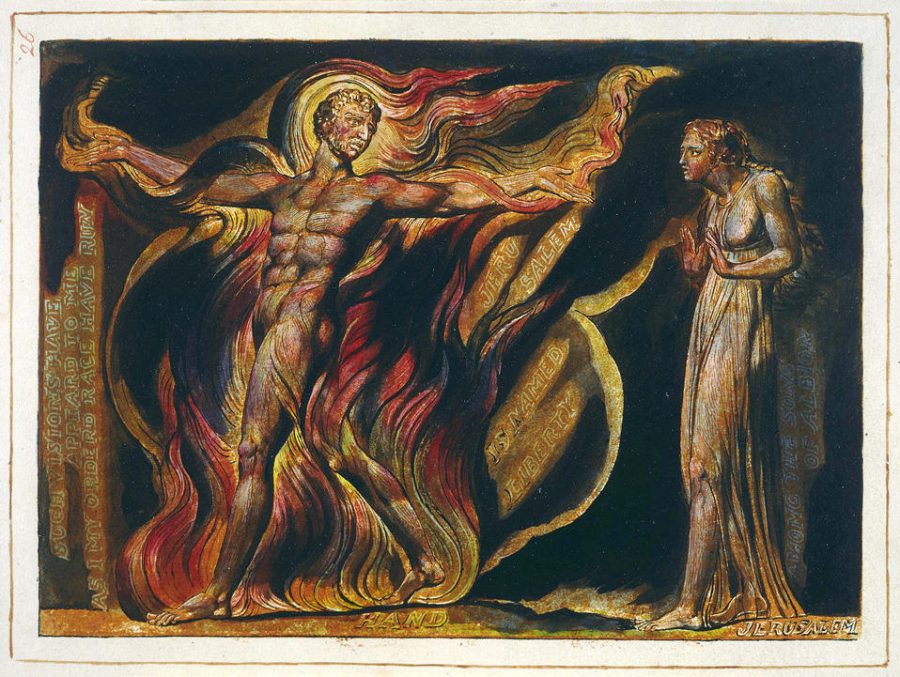

Your beauty is beyond compare

With flaming locks of auburn hair

With ivory skin and eyes of emerald green

Your smile is like a breath of spring

Your voice is soft like summer rain

And I cannot compete with you, Jolene

He talks about you in his sleep

There’s nothing I can do to keep

From crying when he calls your name, Jolene

And I can easily understand

How you could easily take my man

But you don’t know what he means to me, Jolene

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

I’m begging of you please don’t take my man

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

Please don’t take him just because you can

You could have your choice of men

But I could never love again

He’s the only one for me, Jolene

I had to have this talk with you

My happiness depends on you

And whatever you decide to do, Jolene

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

I’m begging of you please don’t take my man

Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Jolene

Please don’t take him even though you can

Jolene, Jolene

via @WFMU

Related Content:

Feel Strangely Nostalgic as You Hear Classic Songs Reworked to Sound as If They’re Playing in an Empty Shopping Mall: David Bowie, Toto, Ah-ha & More

Hear Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Shifted from Minor to Major Key, and Radiohead’s “Creep” Moved from Major to Minor

R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion” Reworked from Minor to Major Scale

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 24 for another monthly installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.