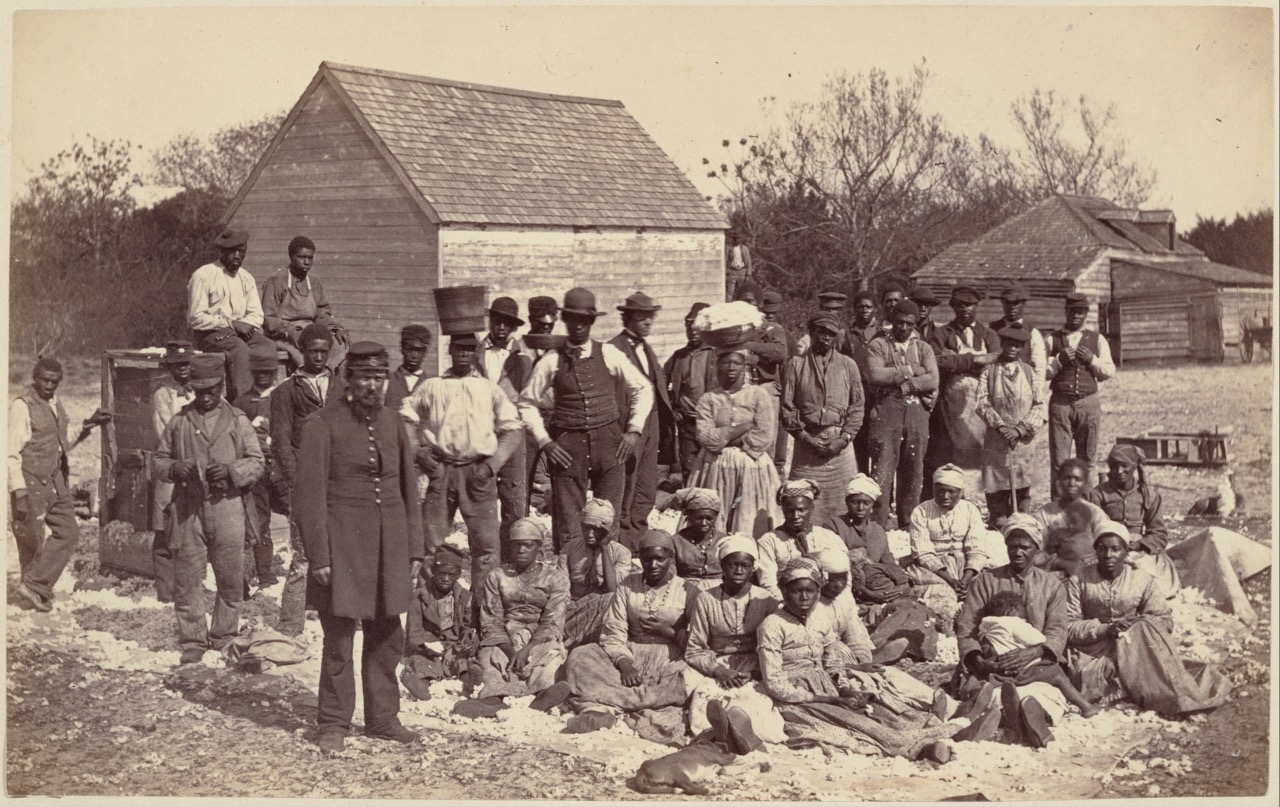

Throughout the history of the so-called “New World,” people of African descent have faced a yawning chasm where their ancestry should be. People bought and sold to labor on plantations lost not only their names but their connections to their language, tradition, and culture. Very few who descend from this painful legacy know exactly where their ancestors came from. The situation contributes to what Toni Morrison calls the “dehistoricizing allegory” of race, a condition of “foreclosure rather than disclosure.” To compound the loss, most descendants of slaves have been unable to trace their ancestry further back than 1870, the first year in which the Census listed African Americans by name.

But the recent work of several enterprising scholars is helping to disclose the histories of enslaved people in the Americas. For example, The Freedman’s Bureau Project has made 1.5 million documents available to the public, in a searchable database that combines traditional scholarship with digital crowdsourcing.

And now, a just-announced Michigan State University project—supported by a $1.5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation—will seek to “change the way scholars and the public understand African slavery.” Called “Enslaved: The People of the Historic Slave Trade,” the multi-phase endeavor is expected to take 18 months to complete an “online hub,” reports Smithsonian, linking together dozens of databases from all over the world.

“By linking data collections from multiple universities,” writes MSU Today, the resulting website “will allow people to search millions of pieces of slave data to identify enslaved individuals and their descendants from a central source. Users can also run analyses of enslaved populations and create maps, charts and graphics.” The project is headed by MSU’s Dean Rehberger, director of Matrix: The Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at MSU; Ethan Watrall, assistant professor of anthropology; and Walter Hawthorne, professor and chair of MSU’s history department and a specialist in African and African American history.

In addition to publishing several books on the Atlantic slave trade, Hawthorne has worked on previous digital history projects like the website Slave Biographies, which compiles information on the “names, ethnicities, skills, occupations, and illnesses” of enslaved individuals in Maranhão, Brazil and colonial Louisiana. In the video above, you can see him describe this latest project, which coincides with MSU’s “Year of Global Africa,” an 18-month celebration of the university’s many partnerships on the continent and “throughout the African Diaspora.”

Digital history projects like those spearheaded by Hawthorne and other researchers help not only scholars but also the general public develop a much more nuanced understanding of the history of slavery. These tools provide a wealth of information, but they cannot truly capture the emotional and psychological impact of the history. For such an understanding, Morrison said in the first of her 2016 Harvard Norton lectures, “I look to literature for guidance.”

Related Content:

African-American History: Modern Freedom Struggle (A Free Course from Stanford)

The Anti-Slavery Alphabet: 1846 Book Teaches Kids the ABCs of Slavery’s Evils

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

er

er