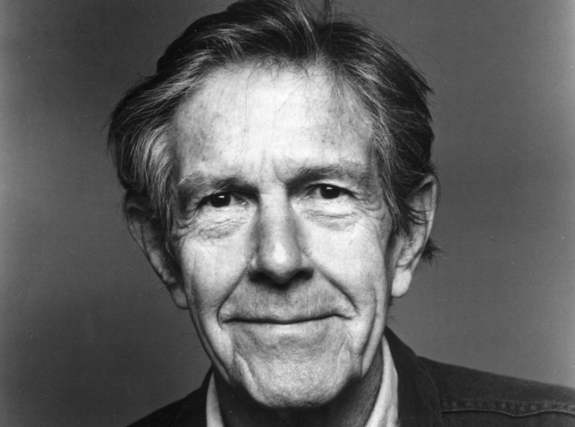

The friendship of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus ended, famously, in 1951. That year, increasingly fractious political tensions between the two philosopher-writers came to a head over the publication of Camus’ The Rebel, a book-length essay that marked a departure from revolutionary thought and a turn toward a more pragmatic individualism (as well as recalling the anarcho-syndicalism Camus had embraced in the 30s). The doctrinaire Sartre and his intellectual coterie took exception, and while Sartre further pursued a Marxist political program, informed by a critique of racism and colonialism, Camus confronted the absurd; he “begins to sound more like Samuel Beckett,” writes Andy Martin at the New York Times’ philosophy blog, “all alone, in the night, between continents, far away from everything.”

The two split not only over ideas, however: after the war, Camus became increasingly disillusioned with Stalin’s totalitarian Soviet rule, while Sartre made what Camus considered weak attempts to defend or excuse the regime’s crimes. At first, writes Volker Hage in Der Spiegel, their disagreements were “limited to a relatively small group of intellectuals.” Then Sartre published Francis Jeanson’s scathing review of The Rebel in the journal Sartre founded in 1945, Les Temps Modernes. (See Jeanson discuss the review in the video interview below, excerpted from the short documentary on Sartre and Camus at the top of the post). Camus, Hage writes, “made the mistake of sending a long rejoinder. What followed was a tragic dissolution of what had once been a friendship.”

Sartre made his final kiss-off very public, printing in Les Temps Modernes a “merciless” response, “insidious and malicious, yet also a magnificent masterpiece of personal polemics.” Almost ten years later, in 1960, Camus was killed in a car accident at the age of 46. Though the two never formally reconciled, Sartre penned a heartfelt tribute to his former friend in The Reporter that contained none of the vitriol of his past condemnations. Instead, he describes their falling out in the terms one might use for a former lover:

He and I had quarreled. A quarrel doesn’t matter — even if those who quarrel never see each other again — just another way of living together without losing sight of one another in the narrow little world that is allotted us. It didn’t keep me from thinking of him, from feeling that his eyes were on the book or newspaper I was reading and wondering: “What does he think of it? What does he think of it at this moment?”

Sartre confesses his uneasiness with Camus’ moody silence, “which according to events and my mood I considered sometimes too cautious and sometimes too painful.” It was a silence that seemingly overtook Camus in his final years as he retreated from public life, and though Camus’ fierce individualism lay at the heart of their falling-out, Sartre wrote in deep appreciation of his friend and antagonist’s solitude and stubborn resoluteness:

He represented in our time the latest example of that long line of moralistes whose works constitute perhaps the most original element in French letters. His obstinate humanism, narrow and pure, austere and sensual, waged an uncertain war against the massive and formless events of the time. But on the other hand through his dogged rejections he reaffirmed, at the heart of our epoch, against the Machiavellians and against the Idol of realism, the existence of the moral issue.

In a way, he was that resolute affirmation. Anyone who read or reflected encountered the human values he held in his fist; he questioned the political act. One had to avoid him or fight him-he was indispensable to that tension which makes intellectual life what it is.

Camus’ “silence,” the theme of Sartre’s tribute, “had something positive about it.” The former harshness of Sartre’s critiques softens as he chides Camus’ refusal “to leave the safe ground of morality and venture on the uncertain paths of practicality.” Camus’ confrontation with the Absurd, writes Sartre, with “the conflicts he kept hidden… both requires and condemns revolt.”

At the bitter end of their friendship, Sartre viciously condemned the contradictions of Camus’ political thought as the product of personal failings, telling him, “You have become the victim of an excessive sullenness that masks your internal problems. Sooner or later, someone would have told you, so it might as well be me.” In his final tribute to Camus, he returns to this idea, in much different language, writing that, at the age of 20, Camus had become “suddenly afflicted with a malady that upset his whole life”; he had “discovered the Absurd—the senseless negation of man.” Rather than succumbing, however—Sartre writes—Camus “became accustomed to it, he thought out his unbearable condition, he came through.”

After the car accident, Sartre acknowledged Camus’ fierce individualism and principle in the face of life’s absurdity as an existential triumph rather than a handicap: “We shall recognize in that work and in the life that is inseparable from it the pure and victorious attempt of one man to snatch every instant of his existence from his future death.”

Read the full tribute essay in a downloadable PDF format here.

Related Content:

Albert Camus Writes a Friendly Letter to Jean-Paul Sartre Before Their Personal and Philosophical Rift

Hear Albert Camus Deliver His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech (1957)

The Absurd Philosophy of Albert Camus Presented in a Short Animated Film by Alain De Botton

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness