Sexual violence in India has been in the spotlight ever since a 23-year-old medical student was gang raped and murdered on a bus in New Delhi in 2012. The crime was so flagrant and so brutal that the country recoiled in shock. Students and activists descended into the streets of Delhi to protest.

Filmmaker Ram Devineni realized just how entrenched the problem is in Indian culture when he spoke with a cop during one of those protests. As he told the BBC,“I was talking to a police officer when he said something that I found very surprising. He said ‘no good girl walks alone at night.’

The Indian government rushed legislation that would increase the prison term for rape along with criminalizing other crimes against women like stalking. Yet, a string of other high-profile rapes, including a few against foreign tourists, show that this is a continuing problem, one that wasn’t going to be solved with a few laws.

“I realized that rape and sexual violence in India was a cultural issue,” said Devineni. “And that it was backed by patriarchy, misogyny and people’s perceptions.”

So Devineni decided to try and change India’s culture with one of the most powerful weapons out there: art.

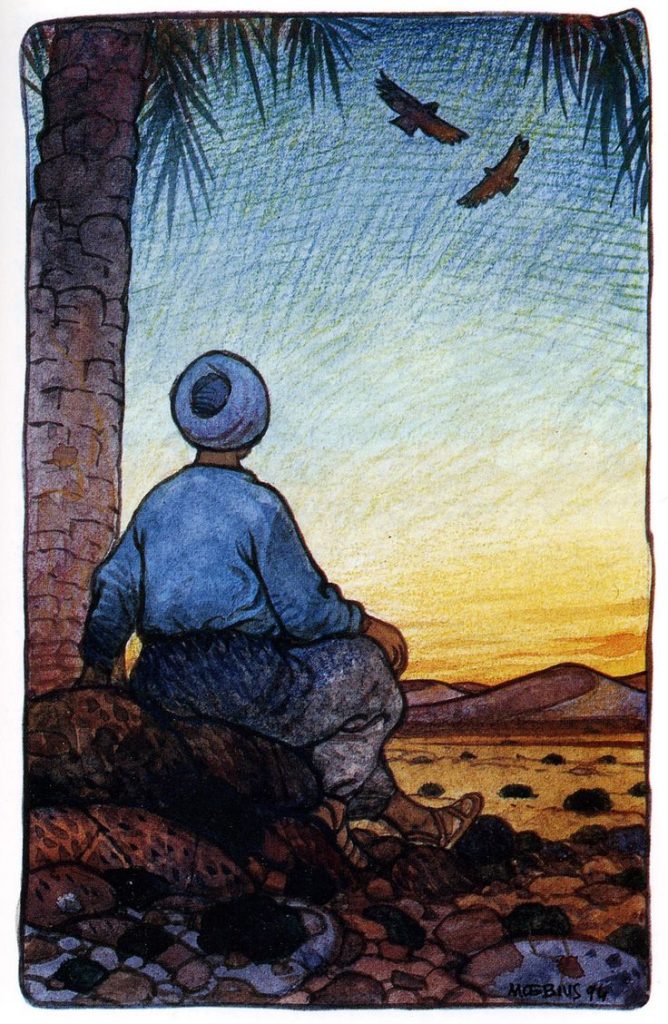

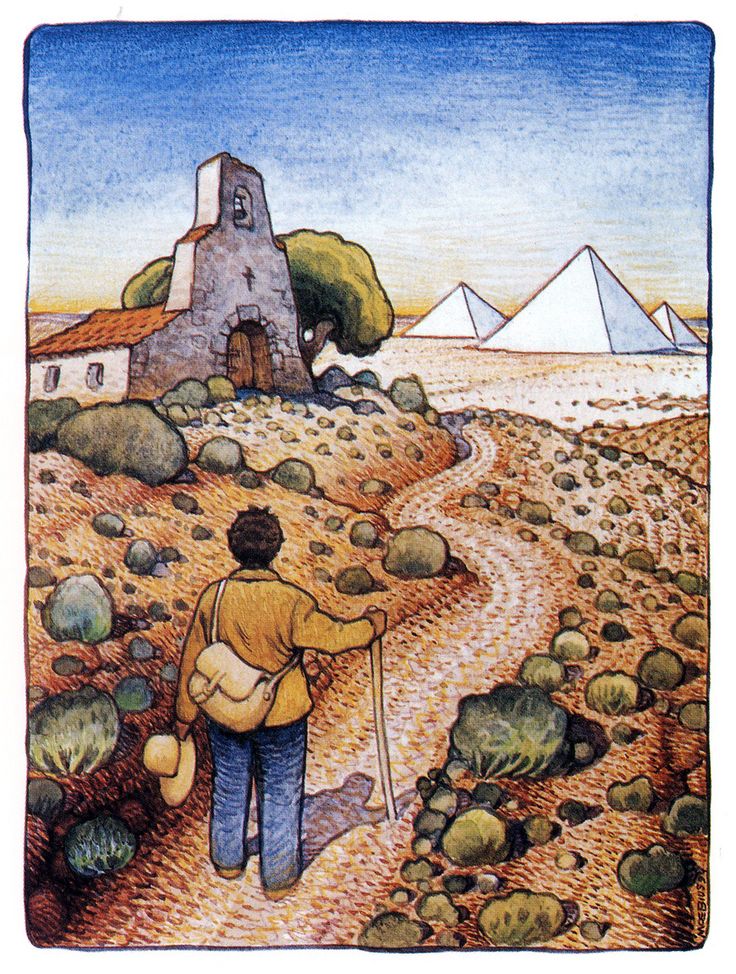

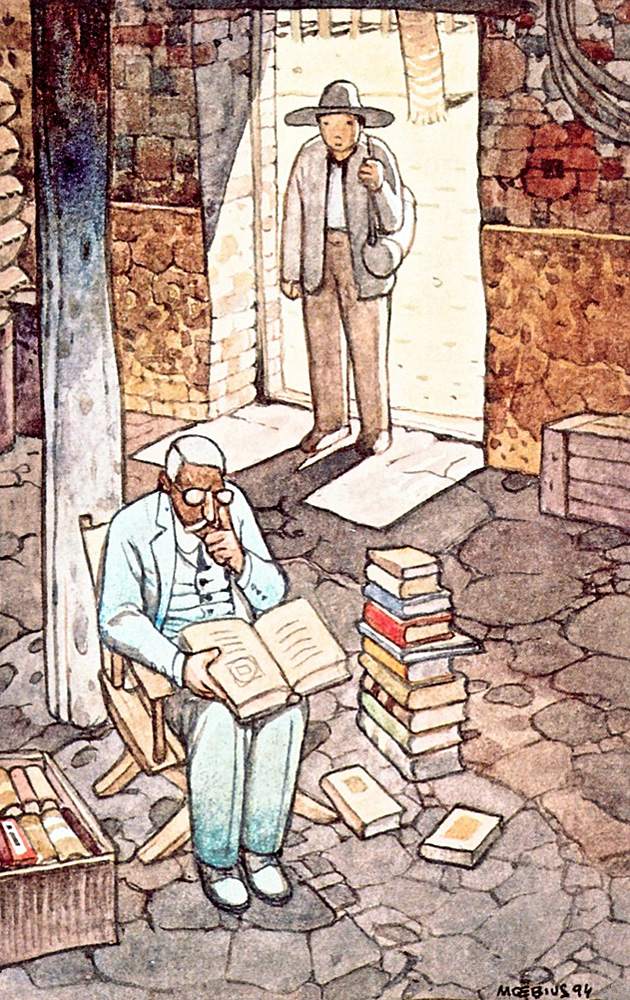

Inspired by Hindu mythology, Devineni and a couple collaborators created a graphic novel about Priya, a rape survivor who appeals for help to Parvati, the Goddess of power and beauty. By the end of the comic, Priya confronts her attackers while riding a tiger.

As a continuation of the project, Devineni created Parvati Saves the World, a similar story pieced together from some amazingly kitschy Bollywood epics from the 1970s. He described the project as being “like DJ Spooky’s remix of Birth of a Nation but this focuses on sexual violence.”

In the film, Priya once again appeals to Parvati after getting attacked, this time by the friend of a prideful king. When Parvati confronts the king, he tries to assault her. This is a bad move. Her husband is the God Shiva, AKA “the Destroyer,” AKA someone you really don’t want to tick off. As punishment, he brings fire and death on heaven and earth. Realizing that violence isn’t the answer, Parvati goes to Earth to become “a beacon of hope for oppressed women everywhere.”

You can watch Parvati Saves the World in three parts above. You can learn more about Devineni’s mission at The Creator’s Project.

Related Content:

Bertrand Russell’s Improbable Appearance in a Bollywood Film (1967)

Ravi Shankar Gives George Harrison a Sitar Lesson … and Other Vintage Footage

George Harrison’s Mystical, Fisheye Self-Portraits Taken in India (1966)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.