What do you think of when you hear the word “mime.”

A cheeky, stripe-shirted, invisible ladder-climbing public nuisance?

The solitary practitioner Dustin Hoffman wordlessly toppled in the 1982 film Tootsie?

Or Marcel Marceau?

Ah ha, and what does the name “Marcel Marceau” bring to mind?

The cheeky, stripe shirted, butterfly chasing Bip (who maybe causes you to cringe a little, despite his creator’s reputation as a great artist)?

I was surprised to learn that he was a former French Resistance fighter, whose first review was printed in Stars and Stripes after he accepted an American general’s spur of the moment invitation to perform for 3,000 GIs in 1945 Frankfurt.

The film above documents a 1965 performance of his most celebrated piece, Youth, Maturity, Old Age, and Death, given at 42, the exact midpoint of his life. In four abstract minutes, he progresses through the seven ages of man, relying on nuances of gait and posture to convey each stage.

He performed it countless times throughout his extraordinary career, never straying from his own precisely rendered choreography. The playing area is just a few feet in diameter.

Observe the 1975 performance that filmmaker John Barnes captured for his series Marcel Marceau’s Art of Silence, below. Nothing left to chance there, from the timing of the smallest abdominal isolations to the angle of his head in the final tableau.

Time’s effects may have provided the subject for the piece, but its perennially lithe author claimed not to concern himself with age, telling the New York Times in 1993 that his focus was on “life-force and creation.”

Later in the same interview, he reflected:

When I started, I hunted butterflies. Later, I began to remember the war and I began to dig deeper, into misery, into solitude, into the fight of human souls against robots.

This would seem to support the theory that maturity is a side effect of age.

His alter ego Bip’s legacy may be the infernal invisible ropes and glass cages that are a mime’s stock in trade, but distilling human experience to its purest expression was the basis of Marceau’s silent art.

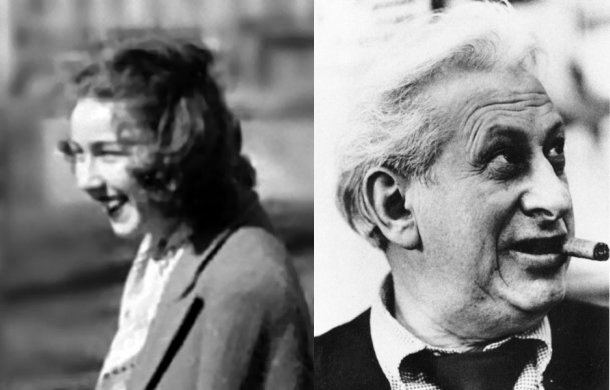

In a recent appreciation published in the Paris Review, author Mave Fellowes considers the many stages of Marceau, from the formative effects of childhood encounters with Charlie Chaplin films to his death at 84:

He feels his advancing age and fears that the art of mime will die with him. It’s a transitory, ephemeral art, he explains, as it exists only in the moment. As an old man, he works harder than ever, performing three hundred times a year, teaching four hours a day. He is named the UN Ambassador for Aging. Five nights a week he smears the white paint over his face, draws in the red bud at the center of his lips, follows the line of his eyelid with a black pencil. And then takes to the stage, his sideburns frayed, his hair dyed chestnut and combed forward, looking like a toupee.

His body is as elastic as ever, but the old suit of Bip hangs loose on him now. Beneath the whitened jawline is a baggy, sinewy neck. With each contortion of his face, the white paint reveals deep lines. At the end of his show, he folds in a deep bow and the knobs of his spine show above the low cut of Bip’s Breton top.

Related Content:

Édith Piaf’s Moving Performance of ‘La Vie en Rose’ on French TV, 1954

David Bowie Launches His Acting Career in the Avant-Garde Play Pierrot in Turquoise (1967)

Klaus Nomi: The Brilliant Performance of a Dying Man

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. In college, she earned a hundred dollars for appearing as a mime before a convention of hungover glassware salesmen, an experience briefly recalled in her memoir, Job Hopper. Follow her @AyunHalliday