Given the length of the average haircut, it surprises me that I don’t see more short films built around them. Tamar Simon Hoffs knew the advantages of the haircut-based short film, and she put them to use in 1982, during her time in the American Film Institute’s Directing Workshops for Women program. The Haircut’s script has a busy record executive on his way to an important lunch appointment. With only fifteen minutes to spare, he drops into Russo’s barber shop for a trim. Little does he expect that, within those fifteen minutes, he’ll not only get his hair cut, but enjoy a shave, a massage, a glass of wine, several musical numbers, romance real or imagined, and something close to a psychoanalytic session. He goes through quite a few facets of the human experience right there in the chair — minus the time-consuming “hot towel treatment” — and Russo and his colorful, efficient crew still get him out of the door on time. Hoffs knew the perfect actor for the starring role: John Cassavetes. What’s more, she knew him personally.

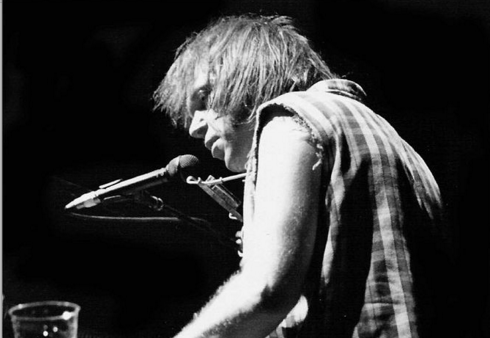

The connection came through her friend Elizabeth Gazzara, daughter of a certain Ben Gazzara, star of the The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, my own favorite Cassavetes-directed film. After reading the script, Cassavetes agreed to perform, “his only stipulation being that his co-stars must be entirely rehearsed and ready to go, so he could just come in and perform as if he really was the customer,” writes British Film Institute DVD producer James Blackford. “Even in a little film such as this, Cassavetes was still searching for those perfect moments that come from the spontaneity of early takes.” You’ll even laugh at a few lines, spoken by Cassavetes as his character begins to enjoy himself, that must surely have come out of his beloved improvisational methods. And we can credit the film’s surprising end to an even more personal connection of Hoffs’: to her daughter Susanna, frontwoman of The Bangles, then known as The Bangs. You can watch The Haircut on the BFI’s new DVD/Blu-Ray release of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, or you can watch it above.

Related Content:

Wes Anderson’s First Short Film: The Black-and-White, Jazz-Scored Bottle Rocket (1992)

The Surreal Short Films of Louis C.K., 1993–1999

Portrait Werner Herzog: The Director’s Autobiographical Short Film from 1986

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.