The films of David Lynch seem anything but “commercial.” Disturbing, incomprehensible, they shine a flashlight into the darkest regions of the subconscious mind. When you walk out of a theater after watching a David Lynch film you feel like you just woke up from a vivid and unsettling dream.

But Lynch has been leading a double life. While making uncompromisingly artistic works for the movie theaters, he has been directing commercials for television and other media on the side. Why does he do it? “Well,” Lynch told Chris Rodley in Lynch on Lynch, “they’re little bitty films, and I always learn something by doing them.”

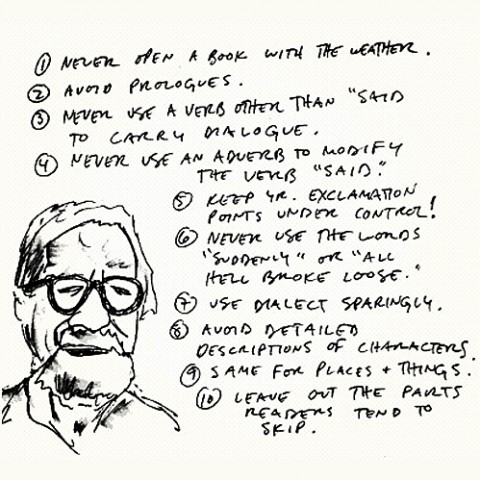

Lynch began receiving offers to make commercials after the critical success of Blue Velvet in 1986. His first project was a series of four 30-second spots for Calvin Klein’s Obsession fragrance in 1988, each with a passage written by a famous novelist. The ad above quotes Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. You can also watch commercials featuring F. Scott Fitzgerald and D.H. Lawrence, but the fourth one, featuring Gustave Flaubert, is currently unavailable.

Lynch has completed many advertising assignments over the years, always managing to retain something of his unique vision in the process. We’ve selected some of the most strikingly “Lynchian” of the commercials. Scroll down and enjoy.

When Lynch was asked a few years ago how he felt about product placement in movies, his videotaped answer went viral on YouTube: “Bullshit. That’s how I feel. Total fucking bullshit.” So it’s strange to think that Lynch once agreed to place the entire fictional world of one of his most famous creations, Twin Peaks, at the service of a Japanese coffee company. But that’s what he did in 1991, for Georgia Coffee. In Lynch on Lynch, the filmmaker was asked whether he was concerned about what the commercials might do to the Twin Peaks image. “Yes,” he replied. “I’m really against it in principle, but they were so much fun to do, and they were only running in Japan and so it just felt OK.”

The four commercials, each only 30 seconds long, follow FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle McLachlan) as he solves the mystery of a missing Japanese woman in the town of Twin Peaks, all the while managing to enjoy plenty of “damn fine” Georgia Coffee. Alas, the Japanese commercials were not as successful as the American TV series. “We were supposed to do a second year, and do four more 30-second spots,” Lynch said, “but they didn’t want to do them.”

You can watch the first episode, “Lost,” above, and follow the rest of the story through these links: Episode Two: “Cherry Pie,” Episode Three: “The Mystery of ‘G’ ” and Episode Four: “The Rescue.”

In 1991 Lynch made one of the creepiest public service messages ever (above) concerning New York City’s rat problem. The cinematography is by Lynch’s longtime collaborator Frederick Elmes.

“Who is Gio” (above) was shot for Georgio Armani in Los Angeles in early 1992, right when several Los Angeles police officers were acquitted in the videotaped beating of black motorist Rodney King–a verdict that sparked mayhem in the streets. “We were shooting the big scene with the musicians and the club the night the riots broke out in LA,” Lynch told Chris Rodley. “Inside the club we were all races and religions, getting along so fantastically, and outside the club the world was coming apart.”

Of all his early advertising clients, Lynch said, Armani gave him the most freedom. The two-and-a-half-minute version above is an extension of the originally broadcast 60-second commercial.

One of the most bizarre of Lynch’s commercials is his 1998 contribution (above) to the “Parisienne People” campaign. The Swiss cigarette maker Parisienne invited famous directors to make short commercials for screening in movie theaters across Switzerland. To see how others handled the same assignment, follow these links: Roman Polanski, Robert Altman, Jean-Luc Godard (with wife Anne-Marie Miéville), Giuseppe Tornatore, and Ethan and Joel Coen.

Lynch’s surreal 2000 commercial for Sony Playstation (above), called “The Third Place,” is wide open for interpretation. Writer Greg Olson takes a heroic stab at it in his book, David Lynch: Beautiful Dark:

For sixty seconds we proceed through a labyrinth of Lynchian themes and motifs visualized in black and white, thus signifying the bifurcation of the world into two polarities. A man in a black suit and a white shirt encounters eerie passageways, sudden flames, barren trees, factory smoke, a woman who won’t speak her secrets, a wounded figure wrapped in bandages. The man meets his own double, and a man with a duck’s head. A sourceless voice asks, “Where are we?” The dualistic duck-man, who synthesizes animal instinct and human learning, knows: “Welcome to the third place.”

Yes. The duck-man knows.

Related Content:

David Lynch Debuts Lady Blue Shanghai

David Lynch’s Organic Coffee (Barbie Head Not Included)

A little food for thought. The Guardian talked with a palliative nurse who has recorded the most common regrets of the dying. It’s worth giving the top five regrets a read, especially if you’re at risk of ending up in the same penitent place. Here, the nurse lists the misgiving most commonly cited by men: “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.”

A little food for thought. The Guardian talked with a palliative nurse who has recorded the most common regrets of the dying. It’s worth giving the top five regrets a read, especially if you’re at risk of ending up in the same penitent place. Here, the nurse lists the misgiving most commonly cited by men: “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.”