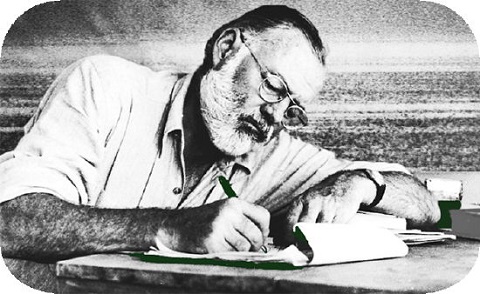

At the web site, The Fertile Fact, you can read lists and lists of things you never knew about your favorite cultural figures. Or rather, you can read lists and lists of guesses about what your favorite cultural figures of the 19th and 20th centuries would have enjoyed about life in our 21st century. From Paul Hendrickson, author of Hemingway’s Boat: Everything He Loved in Life, and Lost, 1934 – 1961, we learn that Papa would have liked e‑mail (“for a man who wrote letters to tune himself up and cool himself down against the day’s ‘real writing’, email would have been a great outlet for his emotion”). But he would have loved Twitter:

Email squared. Hemingway was the master of ‘cable-ese’, a form of slang developed by journalists in the 1920s to save space (and, as importantly, money) when sending telegraphs, which he learned in his youth as a newspaperman. He would have loved the 140-character limit to write small little novels of rage or love or something in between. If he could write an arc of a story in six words, which went: “For Sale: baby shoes, never worn,” thereby arguably inventing flash fiction, then just imagine the possibilities of the kind of War and Peace epics he might have tried via Twitter. And the possible spats he might have got into, of course.

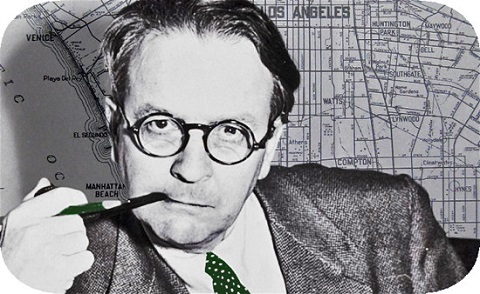

From Tom Williams, author of A Mysterious Something In The Light: A Life of Raymond Chandler, we learn that the creator of Philip Marlowe, another potential Twitter enthusiast, would take to the works of Quentin Tarantino, since

The thing that frustrated Chandler most about Hollywood was that his vision as a writer rarely made it onto screen unmediated. For Ray, the studio always got in the way of what he was trying to do. It was a problem that particularly affected The Blue Dahlia. Though a movie beset by problems (a tight schedule meant Chandler had to write the ending in a state of extreme intoxication) one of the most constant laments in his letters is the studio’s persistent meddling with the picture. He wrote to a friend, shortly after finishing the film, “So here was I a mere writer and a tired one at that screaming at the front office to protect the producer and actually going on the set to direct scenes – I know nothing about directing – in order that the whole project be saved from going down the drain.”

Studios were more interested in getting punters into the theatre than producing good films as far as Chandler was concerned (see the bitter portrait of a studio boss in The Little Sister who talks of caring only for the number of theatres he owns, not the films shown in them, while letting his dog urinate on his trouser cuff). Though Quentin Tarantino is hardly the first director to work independently of a studio, his determination to make the films he wants (proving the value of letting a film-maker stick to his vision in the process) is something Chandler would have admired deeply. Tarantino is also willing to embrace all levels of culture, and this too is something Ray would have respected; he was never one for literary snobbery.

From Robert Zaretsky, author of A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning, we learn that creator of Meursault, the affectless Arab-shooting protagonist of The Stranger, would have approved of The Arab Spring:

The author of The Rebel would find little reason for hope, but none for despair. The instances of non-violent protest in Tunisia and Egypt would serve as illustrations of Camus’ insistence that true rebels never lose sight of the humanity of those who oppress them. Syria? The tragic illustration of what happens when rebels do lose sight of this imperative.

The Fertile Fact offers not only more things these three men would enjoy about our era, but similar lists for such creators as Alfred Hitchcock, Nancy Mitford, Tennessee Williams, and Agatha Christie. How long before they produce one for Virginia Woolf, the writer who, describing “the creative fact,” “the fact that engenders and suggests,” coined the phrase that gave the site its name?

Related Content:

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Raymond Chandler Denounces Strangers on a Train in Sharply-Worded Letter to Alfred Hitchcock

Quentin Tarantino’s 10 Favorite Films of 2013

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.

Leave a Reply