Pablo Picasso had a long and complex relationship with book illustration. The modern painter hated to work on spec and resisted taking commissions. Nonetheless, when it came to literature, he made well over 50 exceptions, illustrating the work of scores of authors he admired. As John Golding writes in The Independent, Picasso had always gravitated toward the literary; he wrote prolifically, was “attracted to art that had a literary flavor,” and “preferred the company of writers, particularly poets, to that of other painters and sculptors.” Golding writes of the artist’s particular love for the Spanish Baroque poet Luis de Gongora, whose work he illustrated in a 1948 edition, and who was to “affect the future development of Picasso’s art in a way that his other literary collaborations did not.” But this may be a hasty judgment. As it turned out, Picasso’s 1931 illustration of a short story by Honoré de Balzac, “The Hidden Masterpiece” (Le Chef‑d’oeuvre inconnu), would affect him greatly, and indirectly contributed to the creation of his most famous work, the enormous anti-war canvas Guernica.

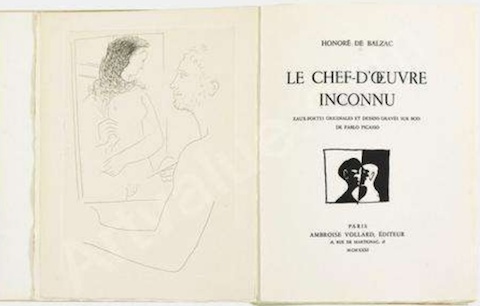

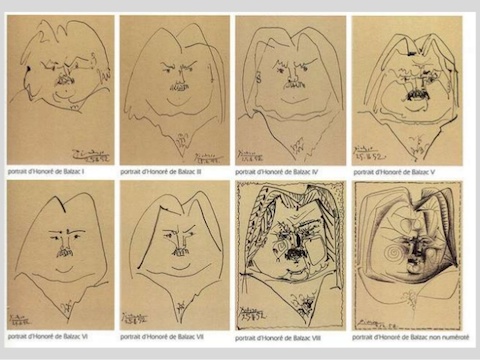

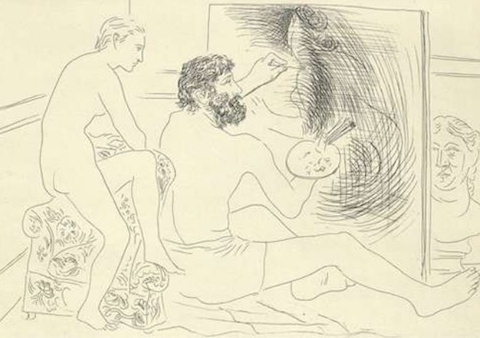

Picasso accepted the Balzac commission from art dealer Ambroise Vollard (see the title page and frontispiece at top, Picasso’s portraits of Balzac above) and completed the thirteen etchings in 1931 for a centennial edition (see ten of the illustrations here). Many have considered these etchings “landmarks in the history of engraving.” Balzac’s story, admired by other painters like Cézanne and Matisse, is among other things a tale of an artist ahead of his time. Set in the 17th century, “The Hidden Masterpiece” tells of an aging painter named Frenhofer, who obsessively labors over a work he has kept secret for years. When two younger admirers, painters Poussin and Porbus, finally manage to see Frenhofer’s secret canvas, they are appalled—it appears to them nothing more than an indistinct mess of lines, colors and shapes—and they mock the older artist and assume their celebrated friend has gone insane. The next day, Frenhofer destroys all his work and kills himself.

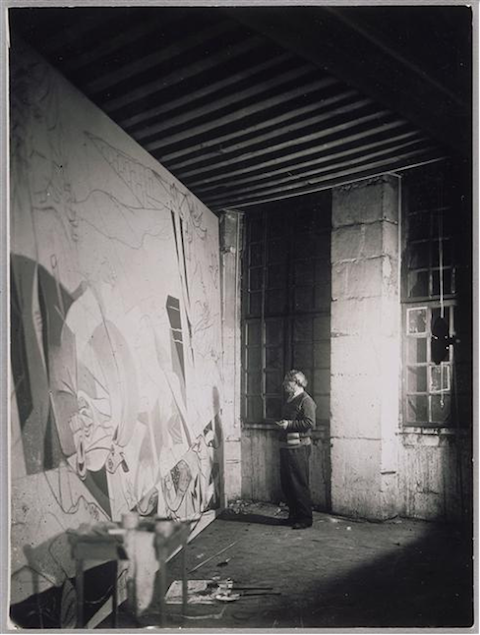

Picasso, writes Thomas Ganzevoort, “had faced something of the same dumbfounded reaction from fellow artists upon showing them his groundbreaking proto-Cubist masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” He later claimed that the ghost of Balzac haunted him, and he found himself so compelled by the story that in 1937, he chose for his new studio a 17th century townhouse located at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustin, the very house many believed to be the setting of the opening scene in “The Hidden Masterpiece.” In April of that year, German warplanes bombed the Spanish Basque city of Guernica, and Picasso abandoned all other projects and set to work on his famous large canvas, which he completed in June of that same year (below, see him in his Grands-Augustin studio, at work on Guernica). Like his earlier, cubist work, Guernica divided critics and perplexed some of his peers. At its unveiling in the 1937 Paris Exhibition, the painting “garnered little attention.” Unlike the tragic Frenhofer of Balzac’s story, however, Picasso did not succumb to self-doubt and lived to see his work vindicated. See this site to learn more about Balzac and Picasso, including discussion of a disputed 1934 drawing some believe to be Picasso’s own “hidden masterpiece.”

Related Content:

Watch Picasso Create Entire Paintings in Magnificent Time-Lapse Film (1956)

A 3D Tour of Picasso’s Guernica

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Speaking of masterpieces, how about some credits and information on that final photograph? (Or did I miss some info using mobile version of the page?)

Hi Bob, the photo is via this excellent blog post, which has many more excellent pics of Picasso’s Paris studio: http://ineedartandcoffee.blogspot.com/2013/04/balzacs-ghost-picasso-at-7-rue-des.html

See here for more of Picasso working on Guernica: http://www.atelierlog.blogspot.com/2013/09/pablo-picasso-13.html