Many fictional locations resist mapping. Our imaginations may thrill, but our mental geolocation software recoils at the impossibilities in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities—a series of geographically whimsical tales told by Marco Polo to Genghis Khan; or China Miéville’s The City and the City, in which two metropolises—Besźel and Ul Qoma—occupy much of the same physical space, and a secretive police power compels citizens to willfully “unsee” one city or the other.

That’s not to say such maps cannot be made. Calvino’s strange cities have been illustrated, if not at street level, in as fanciful a fashion as the narrator describes them. Miéville’s weird cities have received several literal-minded mapping treatments, which perhaps mistake the novel’s careful construction of metaphor for a kind of creative urban planning.

Miéville himself might disavow such attempts, as he disavows one-to-one allegorical readings of his fantastic detective novel—those, for example, that reduce the phenomenon of “unseeing” to an Orwellian means of thought control. “Orwell is a much more overtly allegorical writer,” he tells Theresa DeLucci at Tor, “although it’s always sort of unstable, there’s a certain kind of mapping whereby x means y, a means b.”

Orwell’s speculative worlds are easily decoded, in other words, an opinion shared by many readers of Orwell. But Miéville’s comments aside, there’s an argument to be made that The City and the City’s “unseeing” is the most vividly Orwellian device in recent fiction. And that the fictional world of 1984 does not, perhaps, yield to such simple mapping as we imagine.

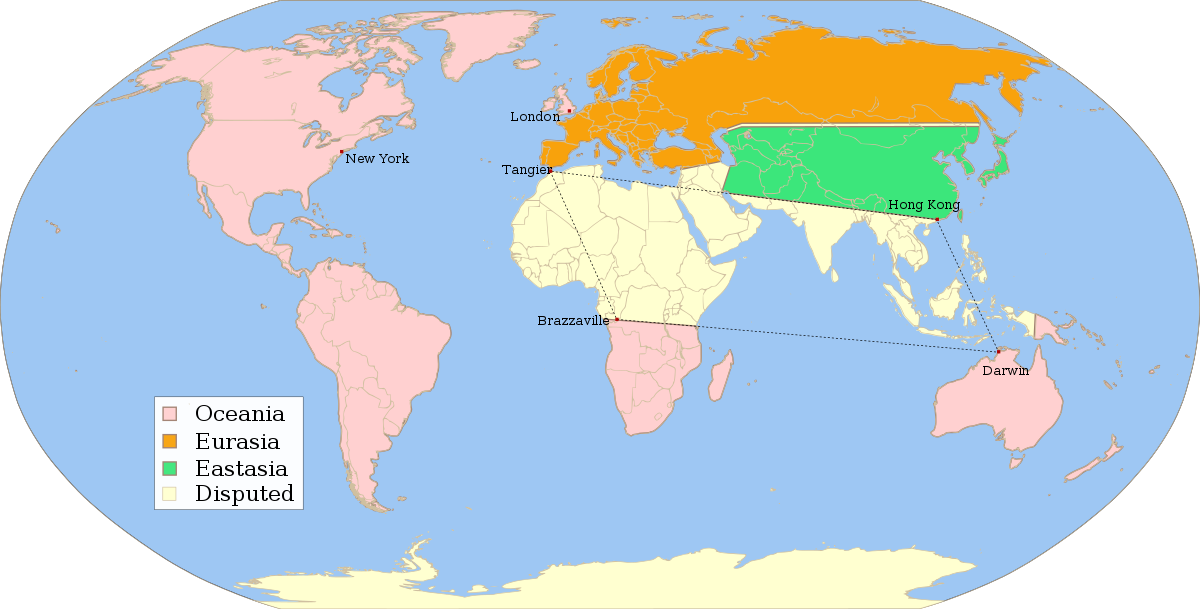

Of course it’s easy to draw a map (see above, or in a larger format here) of the three imperial powers the novel tells us rule the world. Frank Jacobs at Big Think tidily sums them up:

Oceania covers the entire continents of America and Oceania and the British Isles, the main location for the novel, in which they are referred to as ‘Airstrip One’.

Eurasia covers Europe and (more or less) the entire Soviet Union.

Eastasia covers Japan, Korea, China and northern India.

These three superstates are perpetually at war with each other, though who’s at war with whom is unclear. “And yet… the war might just not even be real at all”—for all we know it might be a fabrication of the Ministry of Truth, to manufacture consent for austerity, mass surveillance, forced nationalism, etc. It’s also possible that the entirety of the novel’s geo-politics have been invented out of whole cloth, that “Airstrip One is not an outpost of a greater empire,” Jacobs writes, “but the sole territory under the command of Ingsoc.”

One commenter on the map—which was posted to Reddit last year—points out that “there isn’t any evidence in the book that this is actually how the world is structured.” We must look at the map as doubly fictional, an illustration, Lauren Davis notes at io9, of “how the credulous inhabitant of Airstrip One, armed with only maps distributed by the Ministry of Truth, might view the world, how vast the realm of Oceania seems and how close the supposed enemies in Eurasia.” It is the world as the minds of the novel’s characters conceive it.

All maps, we know, are distortions, shaped by ideology, belief, perspectival bias. 1984’s limited third-person narration enacts the limited views of citizens in a totalitarian state. Such a state necessarily uses force to prevent the people from independently verifying constantly shifting, contradictory pieces of information. But the novel itself states that force is largely irrelevant. “The patrols did not matter… Only the Thought Police mattered.”

In Orwell’s fiction “similar outcomes” as those in totalitarian states, as Noam Chomsky remarks, “can be achieved in free societies like England” through education and mass media control. The most unsettling thing about the seeming simplicity of 1984’s map of the world is that it might look like almost anything else for all the average person knows. Its elementary-school rudiments metaphorically point to frighteningly vast areas of ignorance, and possibilities we can only imagine, since Winston Smith and his compatriots no longer have the ability, even if they had the means.

Related Content:

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

A Complete Reading of George Orwell’s 1984: Aired on Pacifica Radio, 1975

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

There’s some evidence, kind of.

The appendix of 1984, “The Principles of Newspeak”, which suggests that the story is a fiction within a fiction. The story you read is a historical novel written further into the future, as the appendix deals with the events of the novel as being events in the past.

It also explains why, and more importantly here, that, the Party never did, or could, realise its goals, which would suggest that the borders of the world would be at least somewhat close to the general conception of them.

Nonethyeigghty four one five

the kee in my mind to understand the tthrue in tthis bookk

LUCIA RESTELLLO 🙆 my name that i Know

I realise the implications of this only recently. Winston Smith is a Comrade Ogilvy.