At one time, the name Sarah Bernhardt was synonymous with melodramatic self-presentation. In her heyday, the actress created a category all her own—impossible to judge by the usual standards of the dramatic arts. Or as Mark Twain put it, “there are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses—and then there is Sarah Bernhardt.”

Admired and beloved by Victor Hugo and playwright Edmond Rostand, who called her “the queen of the pose and the princess of the gesture,” Bernhardt commanded attention in every role, and became infamous as “a canny self-promoter,” as Hannah Manktelow writes. Bernhardt “cultivated her image as a mysterious, exotic outsider. She claimed to sleep in a coffin and encouraged the circulation of outlandish rumors about her eccentric behavior.”

Bernhardt’s worldwide fame rested not only on her public relations skill, but also on her willingness to take dramatic risks most actresses of the time would never dare. In one notable example, she played Hamlet in 1899, at age 55, in a French adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. What’s more, she boldly undertook the role in London, then again in Stratford at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. Finally, she became the first woman to portray Hamlet on film (see a short clip above).

Reactions to her stage performance by contemporaries were mixed. In her review, actress and writer Elizabeth Robins praised Bernhardt’s “amazing skill” in playing “a spirited boy… with impetuosity, a youthfulness, almost childish.” But Robins issued a qualification at the outset: “for a woman to play at being a man is, surely, a tremendous handicap,” she writes, a criticism echoed by English essayist Max Beerbohm, who went so far as to deny women the power to create art.

“Creative power,” wrote Beerbohm, “the power to conceive ideas and execute them, is an attribute of virility; women are denied it, in so far as they practice art at all, they are aping virility, exceeding their natural sphere. Never does one understand so well the failure of women in art as when one sees them deliberately impersonating men upon the stage.” Setting Beerbohm’s categorically sexist assertions aside (for the moment), we must mark the irony that both he and Robins are troubled by a woman playing a man, given that all of Shakespeare’s female characters were once played by men, a fact both critics somehow fail to mention.

Where Beerbohm saw in Bernhardt’s performance a mere “aping of virility,” Robins, unhampered by Beerbohm’s ugly misogyny, observed the great actress in vivid detail, in an essay that brings Bernhardt’s Hamlet to life with descriptions of her, for example, “appealing dumbly for another sign” after seeing her father’s ghost (on painted gauze), “and passing pathetic fluttering hands over the unresponsive surface, groping piteously like a child in the dark.”

The pathos of Bernhardt’s performance was undercut, Robins felt, by some clumsy moments, such as her mistreatment of poor Yorick’s skull. (A real human skull, by the way, given to her by Victor Hugo). “It was not pleasant,” writes Robins, “to see the grinning object handled so callously…. Indeed, I feel sure that Madame Bernhardt treats her lap-dog more considerately.” On the whole, however, Robins felt the performance a truly dramatic achievement through Bernhardt’s “mastery of sheer poise… of sparing, clean-cut gesture… the effect that the artist in her wanted to produce.”

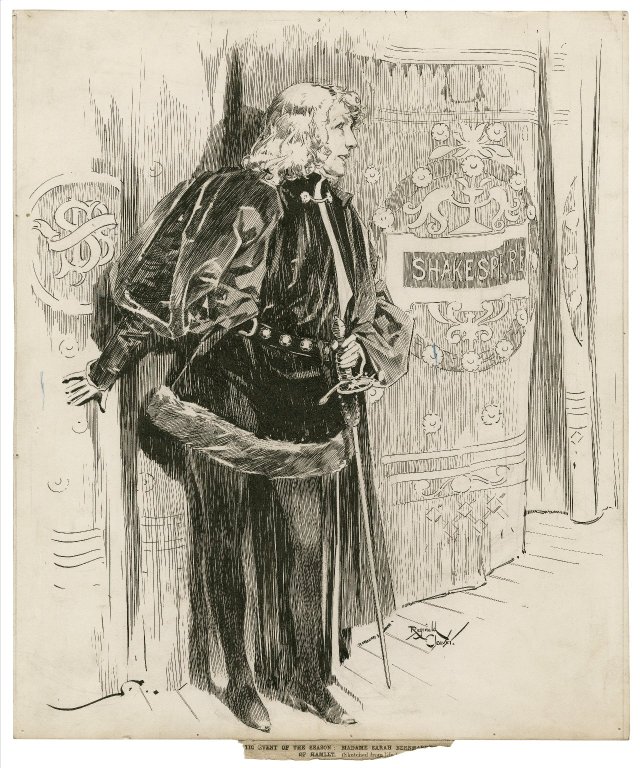

Further up, see an ink drawing of Bernhardt as Hamlet by Reginal Cleaver and, just above, an 1899 postcard photograph (with Hugo’s gifted skull). Read more about Bernhardt’s performance, and the attendant publicity, at the Shakespeare Blog, and learn about a new play based on Bernhardt’s Hamlet called “The Divine Sarah” at the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Shakespeare & Beyond.

Related Content:

When Ira Aldridge Became the First Black Actor to Perform Shakespeare in England (1824)

What Shakespeare’s English Sounded Like, and How We Know It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How cool :)

The title of this article is deeply misleading. Off the top of my head, I know that Charlotte Cushman played the role nearly four decades earlier, and Sarah Siddons well over a century earlier, in 1775. These are well-documented performances with many easily accessible sources. And there certainly *may* have been others even before Siddons.

Bernhardt almost certainly was the first female actor to play Hamlet *on film,* as Jones notes in his article, but the title makes a much broader—and deeply historically inaccurate—assertion.